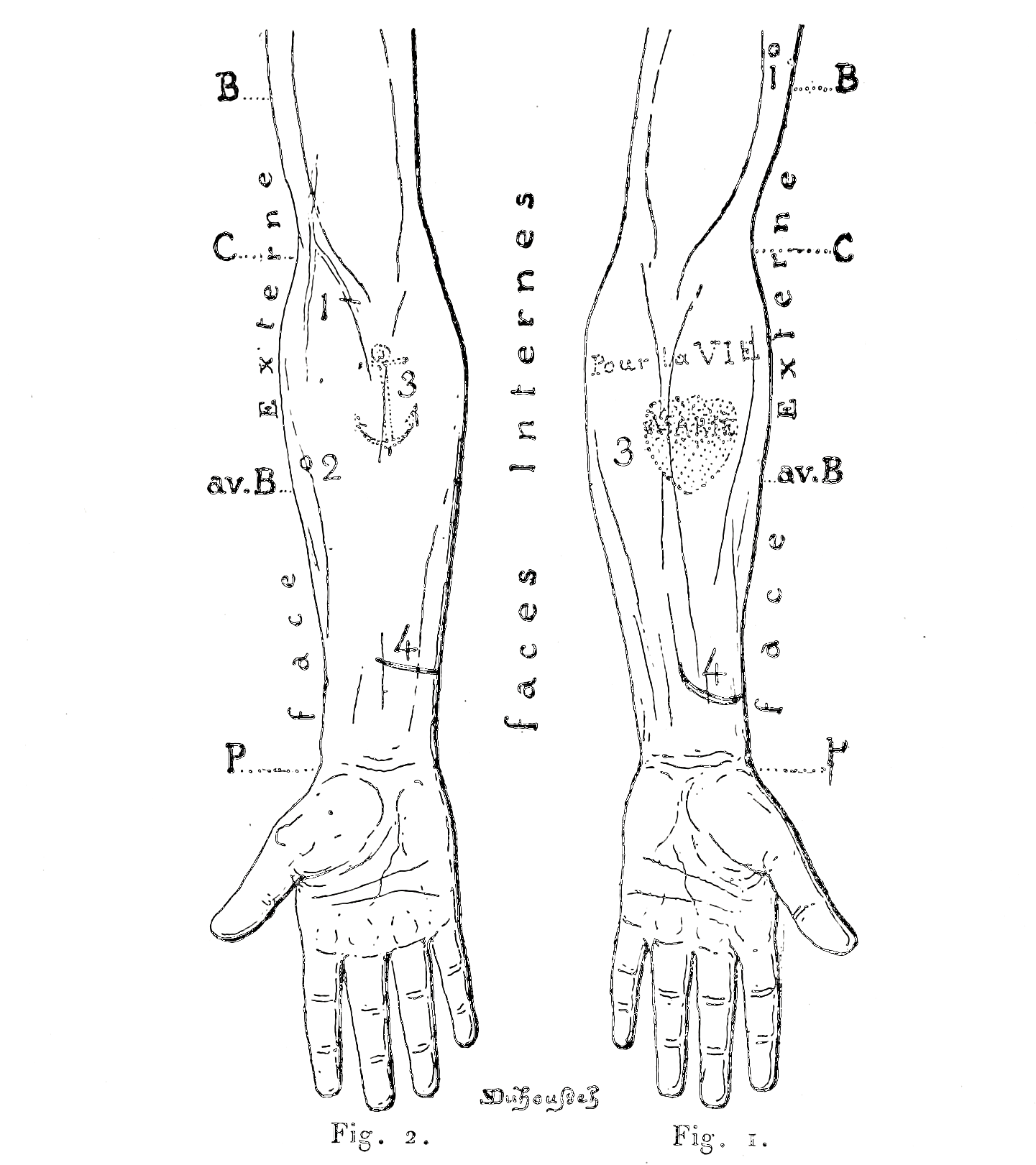

France discovered Elisa Vandamme the day after her death. March 1910: that sixteen-year-old prostitute was strangled by a client and dismembered. The discovery of her head on Botzaris Street led the Parisian police on a sinister treasure hunt for the rest of her body. Her recorded physical description, established during a former encounter with the Préfecture de Police, proved useful for the investigation. It included two tattoos: one was located between her left thumb and index; the other one on her right biceps: it read ‘the Child of Misfortune’. An ironic statement.

The French press used this tragic detail as a starting point to recount her sad existence. Her alcoholic father died in a mental institution; her mother accidentally drowned in the Canal Saint-Martin. Elisa cut cardboard for a living, then started manufacturing shoes. Aged sixteen, she left her aunt’s house because she wanted to ‘be free’. That meant spending every evening soliciting: her usual route went from the Boulevard Ménilmontant to a street near the Place de la République. Elisa Vandamme belonged to the specific world of the Parisian underworld. There, people used the argot slang, had their own specific and strange customs. She was nicknamed ‘La Teigne’, the French word for ‘ringworm’; it’s also slang for a ‘nasty piece of work’. In this world, tattooing was a common occurrence. In the investigation of the Elisa Vandamme case, tattoos served the well-known purpose of helping recognise her body parts. Elisa’s killer was surely aware of this forensic trend: when her hands were recovered after a week of research, the police noticed that the skin between her left thumb and index had been removed. Her tattoos also pointed towards leads. In a city riddled with criminals and delinquents, tattoos could be used as rallying signs for gangs, especially those engraved between those specific fingers. Three, two or five… The newspaper couldn’t seem to agree on the number of tattooed dots on Elisa’s hand nor on the delinquent organisation she was supposed to belong to. Was she part of the ‘Courtille Gang’ or the ‘Ménilmontant’s Apaches?’. It didn’t stop newspaper Le Matin from imagining that Elisa fell victim to a mafia-like revenge.

However, reading between the lines of newspaper articles, we might stumble onto more mundane uses of tattooing in the early 20th century. An important fact is that Elisa Vandamme’s tattoos were visible. However, her friends and family were unaware that she was a prostitute. It hints at the fact that tattoos were not limited to the worlds of crime, delinquency, and prostitution. And this even though the Petit Journal mentioned another ‘equivocal’ tattoo on her right arm. Though located near the ‘Child of Misfortune’ one, it was unknown to the police: she probably had it done recently. Elisa Vandamme even had a fourth tattoo, unrecorded as well. When it came to women, the police were often only aware of the marks left visible with clothes on. It read ‘D. S. C. À Gaby’: an obscure line of letters. According to Le Petit Parisien, it meant ‘Donne Son Cœur à Gaby’: ‘Gives Her Heart to Gaby’. It referred to Gabriel-Antoine, her former companion. Back when she was fourteen and he was sixteen, she had those letters tattooed to ‘prove that she was committed to him’. Their story came to an end soon after, when an argument between Elisa and a deserter led to Gabriel being sent to prison. Though the circumstances remain vague, he was accused of stabbing her. He wasn’t a suspect for long in the 1910 case.

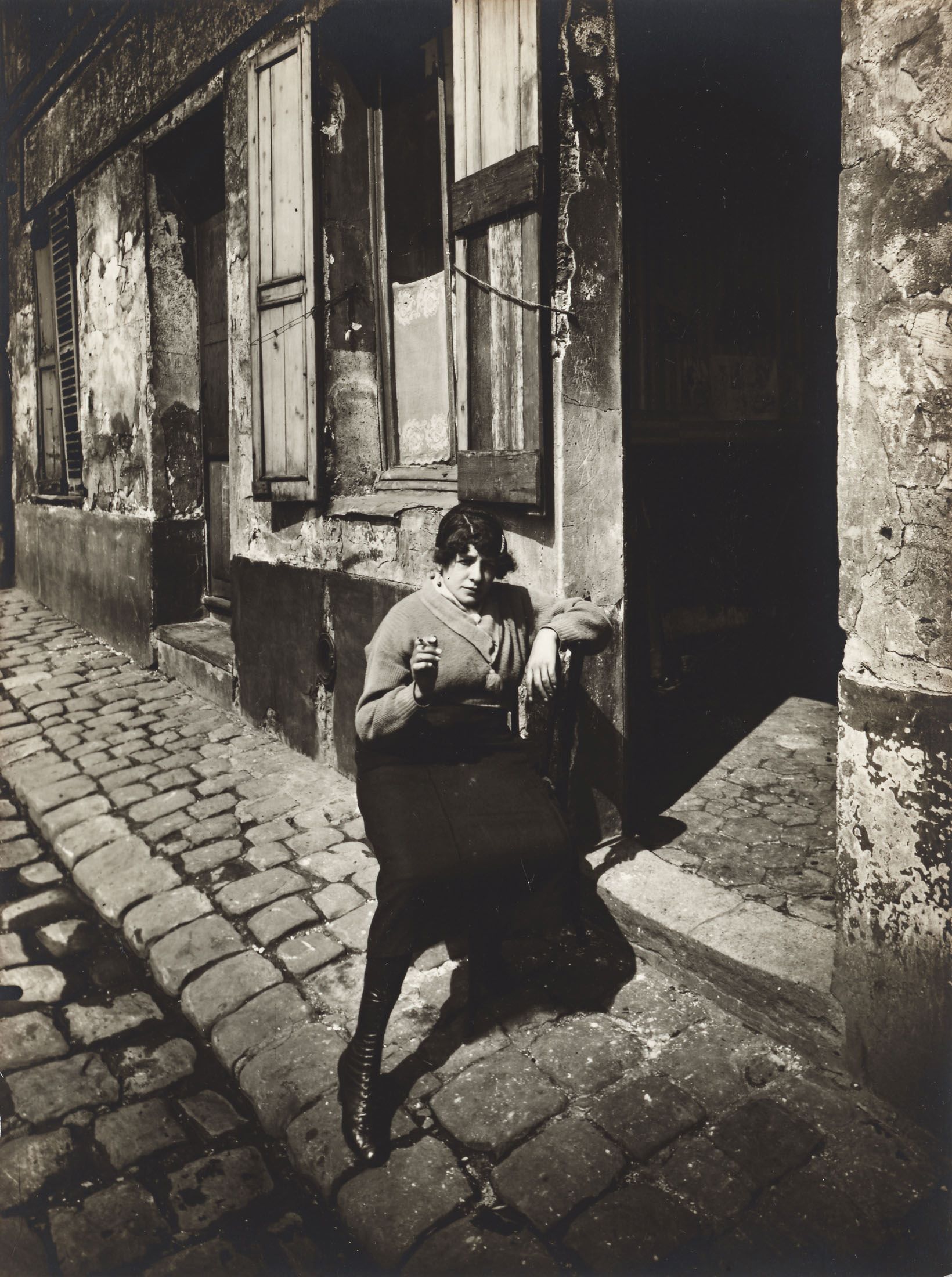

Such tattoos were omnipresent in fiction. In 1889, Oscar Méténier wrote in his novel Madame la Boule: ‘Once marked, you’re marked for life and you will die with it… It’s like marriage, to us who do not care much about mayors and priests.’ The author was a former police station secretary, and this novel was aimed at documenting the life and times of the people he met in his work. Such tattoos were meant to replace proper marriages, back when proper marriages were mostly aimed at the middle class. In 1891, Le Figaro met Parisian tattooer ‘Father Rémy’. He recalled: ‘A lot of women […] come to ask me to tattoo the name of their lover on their arm.’ He specified that he warns them against it, since most of them come to have a change of heart. Elisa’s tattoos are mentioned one last time in the case: they prove the murderer’s thoroughness through the evocation of their careful erasure. Elisa Vandamme, ‘the Child of Misfortune’, will go on to be periodically mentioned by the press. In 1938, a sinister article about a headless man found at Seine-Port mentions the ‘bloody puzzle’ of 1910. Nevertheless, during the two months of this awful case, it shed a light on a practice that often went unnoticed through history: tattooing. And her tattoos served as a last testimony to Elisa’s life story, to her individuality and character. Sources Oscar Méténier, Madame La Boule, Paris, G. Charpentier et Cie, 1889. « L’horrible découverte de la rue Botzaris », Le Petit Journal, 3 mars 1910. « La tête coupée a été reconnue », Le Petit Parisien, 3 mars 1910. « Le mystère de la tête sans corps », Le Petit Parisien, 5 mars 1910. « Deux mains coupées. Sont-ce celles d’Elisa Vandamme ? », Le Petit Journal, 9 mars 1910. « À travers l’Actualité », Le Public, 11 mars 1910. « Le crime de la rue Botzaris », Le Matin, 9 avril 1910. « L’assassin d’Elisa Vandamme raconte son Crime », Le Journal, 11 mai 1910. « Emmanuel Car, « L’homme sans tête de Seine-Port », Détective, 21 avril 1938. Sources des illustrations Eugène Atget, « La Villette. Fille publique faisant le quart », 1921 (Wikimedia – Domaine public). Exemples de localisations de marques particulières issus de Alphonse Bertillon, Identification anthropométrique, instructions signalétiques, Melun, Imprimerie administrative, 1893 (Wikisource – Domaine public). « Les Quat’z-Arts. La gravure », Journal « Le Supplément », carte postale non circulée (collection personnelle). Pour aller plus loin Anne-Claude Ambroise-Rendu, Crimes et délits. Une histoire de la violence de la Belle époque à nos jours, Paris, Nouveau Monde éditions, 2006. Laetitia Gonon, Le Fait divers criminel dans la presse quotidienne française du XIXᵉ siècle. Enjeux stylistiques et littéraires d’un exemple de circulation des discours, Paris, Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2012. Dominique Kalifa, « Crime, faits divers et culture populaire à la fin du XIXe siècle », Genèses. Sciences sociales et histoire, n° 19, 1995, pp. 68-82. Dominique Kalifa, L’Encre et le sang. Récits de crimes et société à la Belle Époque, Paris, Fayard, 1995.