In September 1895, the news broke in French newspaper Le Gaulois: “There is a lady in the British court, the wife of a peer, who has a drawing carved into her skin. Her name is Lady Randolph Churchill.” It spread like wildfire in the Parisian press. And for a good reason as well. The tattoo on the skin of the future mother to Prime Minister Winston Churchill felt like the very embodiment of the British tattooing craze of the late 19th century.

Born Jennie Jerome in 1854 in New York, the “tattooed lady” was the son of an American speculator. She married Lord Randolph Henry Spencer-Churchill on the 15th of April 1874, bringing her father’s fortune to a penniless but titled family. She was known throughout her life as a fairly independent and adventurous woman: she might have had a few love affairs, got married three times, and played an important role in the careers of her husbands and son. In 1895, her husband Randolph died, allegedly from syphilis. When the rumour of her tattooed arm reached France, Jennie Churchill was therefore a young widow: the evocation of her marked body could only feel suggestive in nature. For the press, there was something alluring and risqué in the juxtaposition of her high social status and a tattooed mark, in a time when many French tattooed women were prostitutes. Perhaps her relatively free behaviour only emphasised this paradox.

So, how would she have been tattooed, and where? French newspapers drew their information from an American dispatch. This short article was simultaneously published in many newspapers in November 1894, and found and identified by historian Amelia K. Osterud. It portrays Lord and Lady Churchill returning from India by boat. Jennie Churchill supposedly noticed a “British soldier tattooing a deckhand”, and then asked to see the tattooist’s collection of designs. Charmed by “the Talmudic symbol of eternity – a snake holding its tail in its mouth,” she bared her arm to the tattooist despite her husband’s protest. “But the tattooing was done – so it is said, at least – and it is described as a beautifully executed snake, dark blue in color, with green eyes and red jaws. As a general thing it is hidden from the vulgar gaze by a broad gold bracelet, but her personal friends are privileged to see it and hear the story of the tattooing.” The main features of the tattoo and of its story were settled and immediately copied worldwide. The most important part of it: the tattoo was impossible to verify, as it was purposefully hidden.

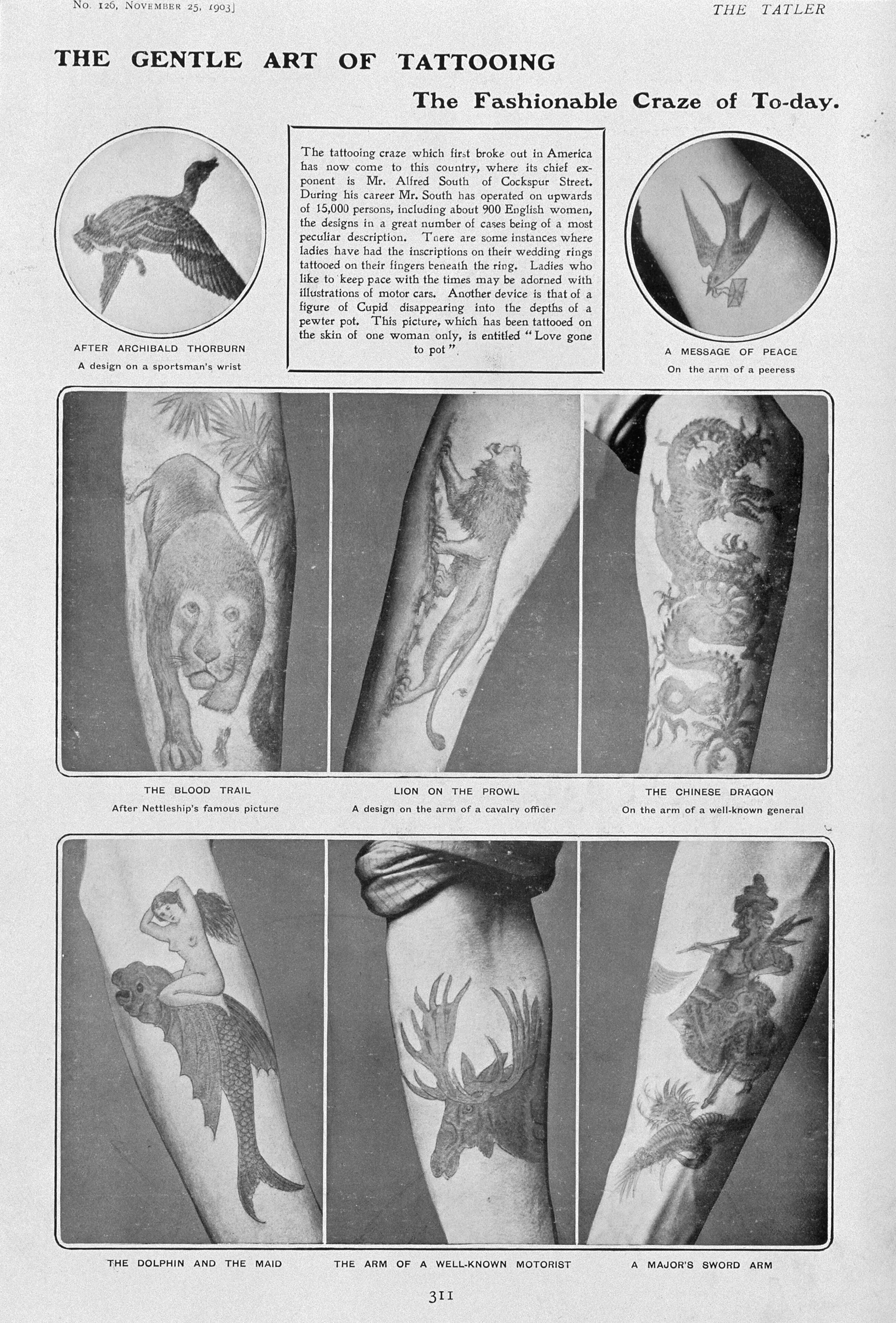

The dispatch reads like a rumour. But at least it’s a plausible one: tattooing was more widely accepted in Britain than it was in France at the time. “Ladies and gentlemen wilfully lend their aristocratic skins to the tattoo artist,” published La Lanterne in September 1894: “It is quite pleasing to hear of such a distasteful habit from neighbours who usually pride themselves on their taste, bon ton and etiquette.” Tattoos were used as souvenirs and proofs of travels: in a time where orientalism was in fashion, tattoos were brought back from foreign countries esteemed for their mastery of this art. Edward VII got a cross tattooed on his arm during a pilgrimage in Jerusalem in 1862; George V was tattooed with a dragon in 1881 in Japan. Tattooing was also becoming fairly common on British soil, which sparked the French fascination with the phenomenon. In September 1894, newspaper Paris spread the news of a new tattoo artist opening his shop to the “ladies” and the “snobs”: it was Sutherland MacDonald and his Jermyn Street’s salon, next to Turkish baths. As a result of the development of a “local” tattoo trade, the number of British tattooed individuals soared in the 1900s. In 1903, l’Echo de Paris estimated their number to 15 000, 900 being “women of then gentry”. Sutherland MacDonald, Alfred South and their colleagues tattooed delicate symbols and monograms on both men and women. They were experts at tattooing without inflicting any pain: MacDonald was known for supposedly using injections of cocaine as an anesthetic. During the Second Anglo-Boer War, newspapers reported that it was becoming fairly common for women to bear the initials of loved ones who had to go away to fight. But was Jennie Churchill tattooed or not? Since the snake on her arm was never photographed, it is highly probable that it was nothing but a legend. However, she remains an important individual in tattoo history. Since she might have been tattooed, she became a prime example of this moment in history where British “tattooed ladies” became a highly discussed topic in the French press. In 1906, Gil Blas even attempted an audacious pun by calling them “femmes de marque”, as they were both distinguished women and marked ones… Behind Jennie Churchill and the mysterious snake of her arm is whole flock of anonymous women who paid visit to the tattoo artist to adorn their bodies. Sources « Fashionable Savages », Globe, 21 octobre 1892. « The Fashion to be Tattooed”, Hull Daily Mail, 11 novembre 1892. Michel Delines, « Chronique. Le tatouage dans le grand monde », Paris, 24 septembre 1894. Tiphaine, « Chronique. Londres tatoué », La Lanterne, 28 septembre 1894. « Ce qui se passe. Échos de Paris », Le Gaulois, 8 septembre 1895. « Échos », Le Mot d’ordre, 15 mai 1895. « Gai ! Gai ! Tatouons-nous ! », L’Écho de Paris, 5 novembre 1903. « Échos. Tatouages », Gil Blas, 5 juin 1906. Sources des illustrations Portrait de Lady Jennie Spencer-Churchill, auteur inconnu, vers 1880 (Wikimedia – Domaine public). Portrait de Lord Randolph Churchill et Lady Jennie Jerome, Georges Penabert, 1874, The Churchill Archives Centre (Wikimedia – Domaine public). “The Gentle Art of Tattooing”, The Tatler, 25 novembre 1903, Wellcome Collection (Domaine public). Further reading Katherine Dauge-Roth, Signing the Body. Marks on Skin in Early Modern France, New York, Routledge, 2020. Alistair O’Neill, London. After a Fashion, Londres, Reaktion Books, 2007. Amelia K. Osterud, « Jennie Churchill and her fabled tattoo », Tattooed lady history, 2015. « Early Modern Tattoos with Matt Lodder », That Shakespeare Life, 1er février 2021.