A people of pirates, head hunters, lumberjacks, planters and tireless travellers, Borneo's Ibans revive the tattoo tradition in order to recover their identity, lost in the limbos of history. We met the elders, whose armours of patang or kelingai - tattoos in the local language - represent roadmaps as much as a spiritual protections.

The tropical night has fallen onto the dense jungle as our canoe touches the sand bank. At this hour, only the python's whistles, the sound of the wind, the tinkling of glasses filled with langkao - the local rice alcohol- , the squeaking of Filipino fags and stories of days gone by, may break the silence. The members of the Iban ethnic group traditionally live in longhouses, big wooden houses on stilts which stretch along a mutual corridor and shelter about 25 families.

Some of them are only accessible via the river, since there is no road or since the existing road is regularly blocked by mudslides. Each longhouse has a representative, a tuai rumah, who gives their name to the village. Here, US is not the acronym for the United States, it rather means Ulu Skrang, the zone above the river Skrang. For administrative convenience after independence, the Malaysian government gathered several tribes under the name Iban, which comprises at least seven sub-groups, each with their own dialect, including the Skrang.

Ibans, also called the Sea Skrang, represent a third of the population of the state of Sarawak. From Java and the Chinese Yunnan, Ibans arrived during the XVIth Century via Kalimantan, a now Indonesian province south of Borneo. Loyal to their reputation of being fierce conquerors, they quickly dominated the other tribes of the fourth largest island in the world, and incidentally adopted and adapted their various tattooing traditions. Sat on a braided straw mattress in Mejong's longhouse, a four hours jeep drive from Kuching, Maja, an old man with very clear blue eyes tells us stories.

Villagers call him " Apai Jantai", Father of Jantai. At the end of world war II he was sent by the government in the neighbouring State of Sabah and then in the protectorate of the Sultanate of Brunei to work as a lumberjack. It was the only conceivable job for the men of Sarawak. "Pepper did not make enough money because our village did not have the means to go and sell it to the merchants on the coast" he explains.

Whole generations of men hit the road for ten to fifteen years, for 500 to 1000 RM (120-240$) a year, cutting down trees with machetes in Sabah, breaking their backs in Brunei's petrol ports, or within the machinery of Singapore's gas industry for the most daring. They came back every three years roughly, to visit their parents, get married and have children. Meanwhile, women were going to the fields, in the pepper, rice and rubber tree plantations. They brought up children and made their own mattresses and clothes. Every time the men came back, they had more and more tattoos.

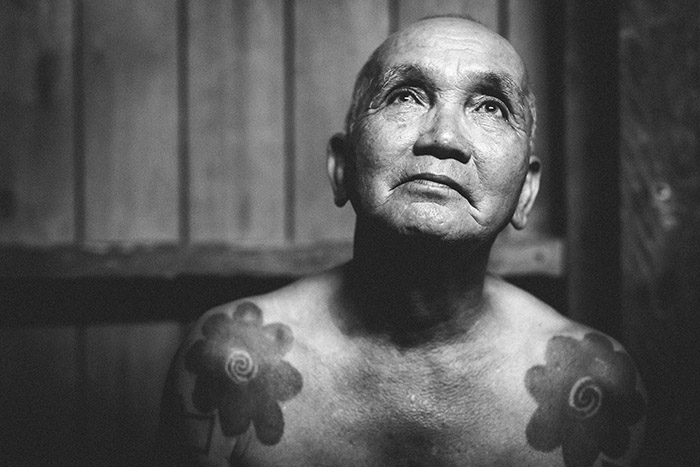

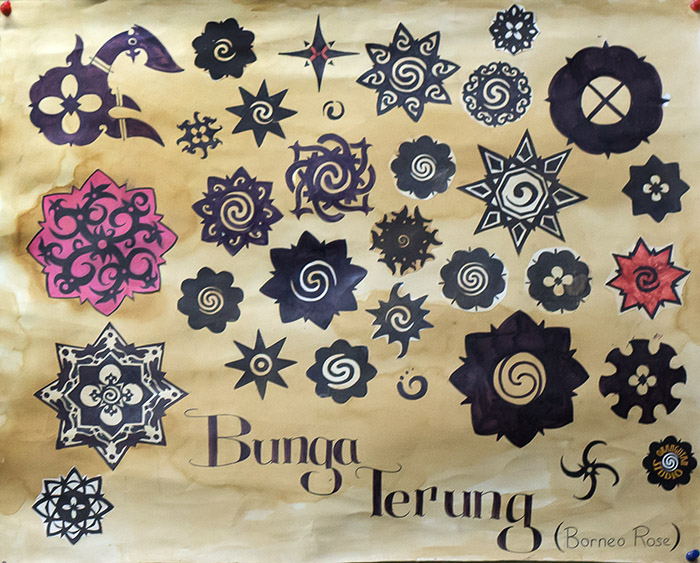

Traditionally, young Ibans begun with a couple of bungai terung tattoos, one on each shoulder. They are inspired by a local eggplant flower, called brinjal. The tattoo symbolised the passage to adult age, it signified a respect of the moral values of the village and signed the young man's departure for the belajai, the initiation journey. These tattoos were opportunely placed by the straps of the wicker bag the young Iban was going to acry during his expedition to "discover the world". For a few months or a few years, he would walk from longhouse to longhouse, offer a hand for everyday chores, refine his knowledge of his own culture, listen to the elders, and in return he received tattoos. During the XXth Century this belajai turned into a temping pilgrimage from job to job, perpetuating the quest for social prestige. The more a man accumulated tattoos, the more he became desirable in the eyes of the women of the community. His marks were the symbols of surmounted obstacles and accumulated riches.

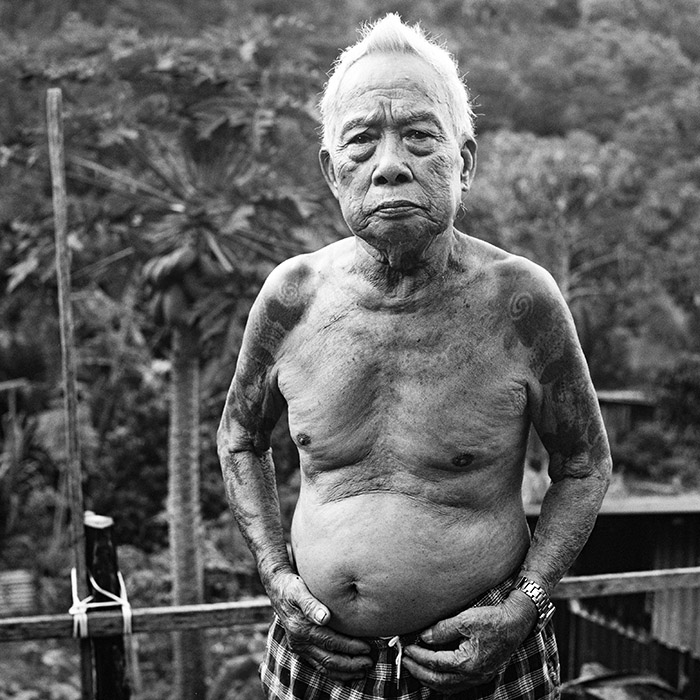

His body would become a journal of his travels and achievements. It is a road book, a passport, a strong sign of identification, which allows Ibans to recognize each other. On Maja's arm, reads a phrase "Salamat kasih semua urang" which means "Thank you everybody", tattooed in the city of Julau. A memory of all the visited place, tattoos are exchanged against an animal or human skull, an amulet or a knife. Metal has a high value, as a basis to make weapons and tools, but it is also offered to the artists so their soul does not soften and they remain hard inside themselves. Strength is needed to tattoo whole bodies on the floor, with just two sticks. "Four people were tattooing my back simultaneously for over ten hours. Not with ink but with candle soot. I drank a lot of langkao to endure the pain" Maja recalls.

On his back forms the tree of life, the story of his existence. At the top, two ketam belakang, a pattern inspired by the shape of a crab, which to him represents a rebate plane, the tool of woodwork, symbol of his years as a lumberjack. On the arm it is called ketam lengan. At the middle of the back a buah engkabang, a maple seed falling like a helicopter, the fruit from which Ibans extract butter and oil. At the bottom the four flowers complete the pattern in an aesthetic fashion. On his chest, Maja wears a small star... it's a plane, he explained. "The first time I saw one flying over the jungle, it was a very mysterious object for us so I had it tattooed, in order not to forget". A great part of Iban beliefs and practices are linked to a free interpretation of the environment. In some villages, elders still listen to bird songs to help them make decisions on a daily basis, and make amulets with what they're inspired with in the jungle, stones and fruits being gifts from the deities.

For Rimong, 70, the star among the flowers on his back represents a precise emotion. "Because I loved looking at stars in the evening with friends. It's a memory that fills me with joy". For the tattooer as much as for the tattooed, the meaning of each piece gives ample room to personal interpretation. On his arm, Rimong wears a tuang, an imaginary creature from his dreams.

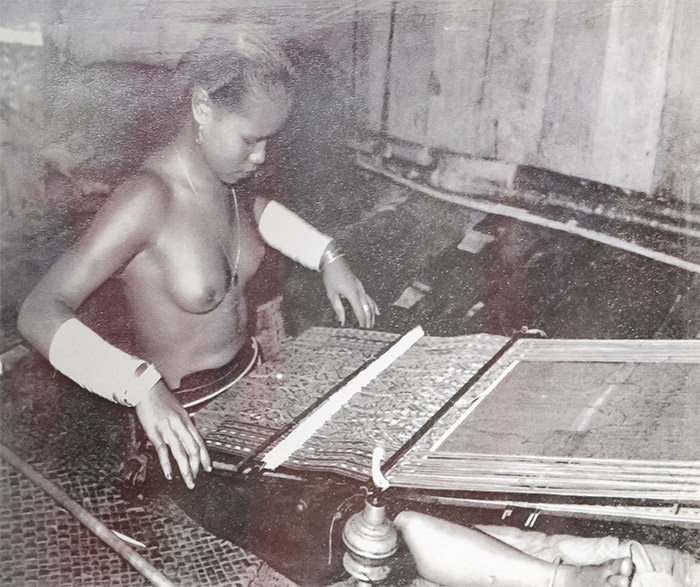

The tattoos are an echo of their spiritual beliefs, the patterns being inspired by the power of animals, plants and humans. Before tattooing, a chicken was sacrificed to appease the spirits and ask for the god's consent. Women of the community respected the same ritual before weaving a pua kumbu, the sacred textile used to wrap the heads freshly brought back by victorious warriors and by shamans before invocatory ceremonies. With the ngajat, a ritual dance, the pua kumbu is another strong piece of Iban heritage.

Like the traditional tattooer invoking the spirits to be guided in the realisation of a pattern, Iban women weaved images that their ancestors showed them in dreams.

It was the kayau indu, the "women's war", practiced for generations while men were cutting the heads of their enemies, to attract the god's favours during fights against other tribes and for the harvest of rice. The best weavers were thanked for their essential contribution to the well-being of the community with a tattoo on their fingers, or a pala tumpa, a circular tattoo on the forearms. Iban women wearing traditional tattoos have almost disappeared today.

Also rare now, the tegulun, a tattoo applied on the fingers of victorious head hunters, the only one to necessitate a religious ceremony. In spite of the peace treatises of 1874 and 1924 between the Dayak tribes, head hunting reappeared sporadically, to eventually disappear at the beginning of the 70ies.

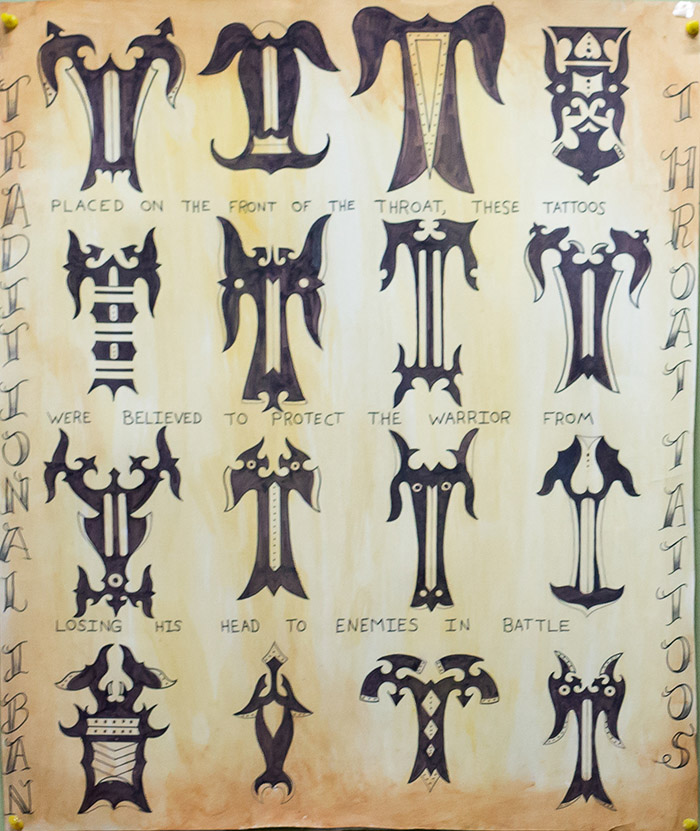

More common, the Ukir rekong, allegory of a scorpion or a dragon on the throat, symbol of strength based on the power of these animals. It protects the necks of warriors against the blades of rival tribes, while the back of the neck is protected by long hair. A good number of men share the motif of the fishing hook on the arm or the leg, a reminder of their activity as fishermen.

This whole cosmos was jeopardized when the Christian missionaries ventured into the jungle to impose the divine word in these villages which had been animists forever. In the kitchens, the gaudy portraits of Jesus and the Virgin Mary in 3D have become the only authorized decoration.

The forced Christianisation that started in the 60ies created a deep breach in these communities. Today, 80 to 90% of the inhabitants are converted in longhouses, some of them become priests, and most of them go to church on Sundays. A church to be found in each minuscule hamlet by the soccer field. In the long house Lenga Entalau, the missionaries arrived late, only fifteen years ago, but they made up for lost time with brutal measures.

All the elders were forced to burn their relics, amulets, remedies and skull-trophies bearers of life, or to throw them in the river. Some of them became ill at the sight of the brazier, as if their soul was consumed at the same time as their precious goods. Some resisted passively, hiding their last skull in a plastic bag at the back of a shed, or entrusting the objects charged with black magic to a son gone to live in the city.

Bryan did not give in. 97 years old and covered with tattoos, he worships seven deities, messengers between men and Petara, the supreme god, as well as the various spirits and ghosts that make the Iban pantheon.

His tattoos protect him against strokes of bad luck. He is convinced of this since he heard a story during world war II. In 1940 some Ibans were enrolled in the British colonial army, where they formed the most part of troops assigned to the protection of the coast of Borneo against a Japanese landing. A waste of time, since the imperial army occupied the island and gave the locals a hard time, starved, tortured and massacred them. A lot of them escaped in the jungle. At the end of the conflict, in collaboration with the Allies, they set up a guerrilla to chase the occupier: it was the Borneo Project. Japanese soldiers dropped like flies under the hits of poisoned blowguns. Bryan was one of those rangers in charge of holding the line against the Japanese, who never managed to reach Ulu Skrang. "One day, an Iban regiment fell into a Japanese trap. The only survivors are those who had kept their amulets and had not converted to Christianity" he asserts.

Today, the young generation has distanced itself from institutionalised religion and a minority is starting to be interested in their ancestors' past. This minority thinks that a degree is not enough to prove one's social worth. Facing constant attacks against native culture by religious people who want to model their soul, by politicians who want to suppress their idiosyncrasy, by business men who devastate their forests with bulldozers - and globalisation sweeping away everything as it passes by, the Iban tattoo is becoming a part of the culture again. More a community than a ritual, more a sign of defiance against the times than a sign of appeasement destined to the gods, adapted to the taste of foreign visitors and sometimes emptied out of its spiritual substance, tattoos remain an important ethnic identification mark facing a terribly uniform world.

" Iban culture and traditions : the pillars of the community's strength " by Steven Beti Anom, a work of reference on the history of this people.

"Panjamon: une expérience de la vie sauvage", by Jean-Yves Domalain, The travel diary of a French naturalist who lived in an Iban tribe at the end of the sixties. Even though he was married to an Iban woman, tattooed and accepted by the community, he had to escape to save his life, poisoned by the village's shaman.

Sarawak (1957) and Life in a Longhouse (1962) by Hedda Morrison, a German photographer known for her pictures of the Beijing of the 30ies and 40ies, and of the Sarawak of the 50ies and 60ies. She lived in this region of Borneo for twenty years, and her photography missions in the district of Kuching granted her a rare access to numerous communities.

Text : Laure Siegel Photos : P-Mod Translation: Armelle Boussidan