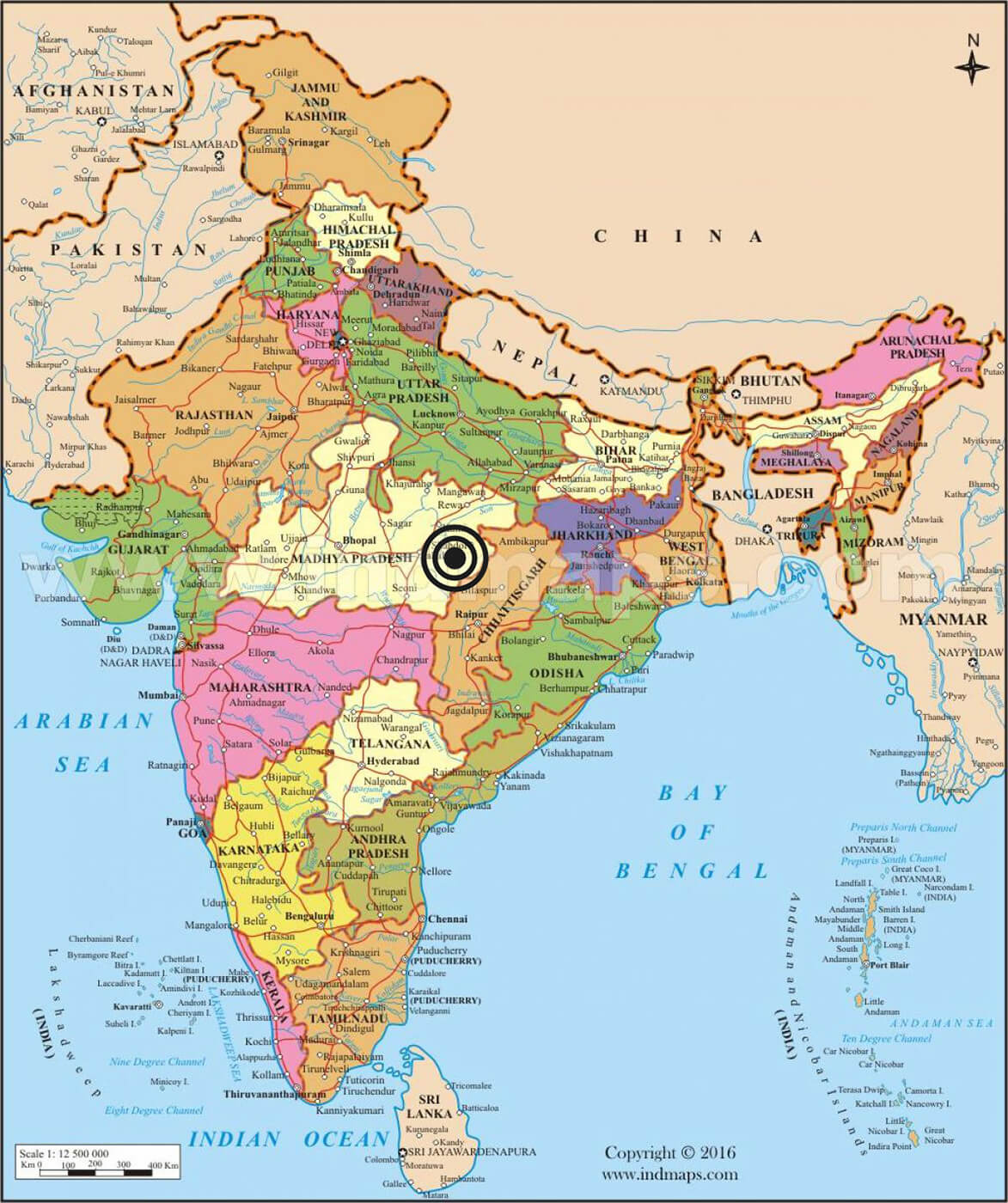

The vast spectrum of Indian tattooing offers 3 perspectives: firstly, the modern and urban tattooing, then, in 2007, close to zero; secondly, the street tattooing intimately linked to popular culture, made of hearts, crosses, bizarre dragons, skulls, names and surnames, Aum, Ganesh and other gods of the vast Hindu pantheon, street practice but that one meets mainly during these big religious gatherings that one calls "mela"; and thirdly, ancestral tattooing, a practice of tribal cultures, of those people whose habits and customs disappear under the steamroller of the modern majority culture.Of these three important aspects of tattoo culture, the last captivated most of my attention. To meet these peoples from one dead end of the world, to witness the past wisdoms and ancestral beliefs at bay, to hit the road for unlikely investigations, to discover unsuspected worlds and improbable peoples, but also to discover and safeguard beautiful patterns and their meanings, that's what I liked the most.Of these ten years spent in the Indian subject, to its various peoples, including some heirs of a very ancient cultural heritage, one of the most beautiful encounters was the one I did with the Baiga, farmers and naturopaths of Madhya Pradesh, in the heart of the vast Indian territory.

Here I am in Baiga country, sporting, satisfied (so far so good), a little of their culture under the sore dermis of my left ankle. But before I could go to visit the Baiga in person it was necessary that my tattoo is treated and that the pain induced by this deep-poking soothed. I decided, a little constrained, to stay quiet for a few days and take a daily picture of the healing process. This photographic ritual only lasted three days, the courage to watch my new tattoo in full light ending on the fourth day.

Morning and evening I cleaned my new body decoration with water and then applied this mixture of turmeric and mustard oil. On the first day, my foot was sore and somewhat swollen, within normal limits. On the second day it was still swollen and the pain had increased. The third day was a continuation of the first two: a little more swollen, a little more painful. The fourth day was the last day I dared to look at my foot in full light, the skin surrounding the tattooed area had taken on an ominous reddish color. The foot was as swollen as the day before but was very painful and limping became my style of ambulation. My "Relaxo" brand flip flops had the colors of Brazil but I was not in the mood to dance samba. From that moment I cleaned my foot in the dim light of my small bathroom without any windows to the outside, opening only one eye to look furtively at the state of my foot in order to make sure that no infection had not triggered. On the fifth day the whole area of the tattoo, and a little beyond, was blackish, just like my thoughts. And it was going to last. Alone, in this little village, the fear of a gangrene would last three weeks, as long as the physical pain lasted. On the tenth day, following an article written by Dr. Chourasia and published in a regional newspaper, in which he gave me the pleasant nickname of "Pardesi Babu" (Mister from elsewhere, Mr. foreigner), I was contacted by a team of journalists from a regional television station, News Express. They wanted to report on Shanti Bai and myself, so they invited me to accompany them to the Maravi village, Lalpur. I was ok, I had something to show this family of tattoo artists, the somewhat catastrophic state of my foot having not seen improvements. I embarked in the 4x4 Sumo of the journalists, also accompanied by Doctor Chourasia who had no explanation for what was happening to my foot. Auuuuum Shanti Auuuuum.

Once at the Maravi's place, I showed my ankle to Shanti Bai and her husband Chamar Singh, who, in a dead silence looked at my tattoo in astonishment. Not very reassuring, I told myself. They had no explanation for me as to the turn of events. The only suggestion they made to me to ward off the spell was to hire a local "shaman." The little man, dressed in his too short pants and his stained tank top, appeared ten minutes later, a handful of dry plants in his hand. A few moments after the arrival of Mister Miracle, my only hope, my only somewhat deflated lifebelt, he knelt down at my feet and began his incantations while waving his plants. All of this, of course, under the greedy lens of the News Express cameraman. Halfway through the incantations, the other journalist interrupted the shaman to ask him to move on or whatever, which irritated me to the highest point. Interrupting the eventual miracle that would save my foot was more than I could emotionally handle. I then asked him angrily to close it or get out. And the prayer resumed its course. This "rescue" mission turned to burlesque.

Then the journalists did the interview with Shanti Bai, surrounded by half of the village too happy that an unexpected event is taking place locally. When everything was recorded, in the box, the journalists satisfied and me, still a little dubious and hardly more reassured than when I arrived, we went back to the car and decided to go to meet the Baigas, in a village far from about thirty kilometers. Halfway there, our team stopped in front of an isolated farm. The Baigas are generally humble and poor farmers, I immediately realized that. Against the backdrop of the farmyard and a Baiga peasant woman accompanied by her four children, Dr. Chourasia was interviewed by our three journalists.

Then we resumed our journey for a few more kilometers, on a winding road in the middle of a pretty dry countryside in this month of January. Once arrived in a rather miserable village, the doctor, accustomed to the place and its inhabitants allowed us to discuss peacefully with some members of the community. In this long-awaited moment, my camera broke down after only twenty photos. The curse continued his work. Fate has a sense of humor that I do not always understand. Fortunately, during these three weeks of limping around in the Dindori district, my daily discussions with Doctor Chourasia provided me with many insights into this unique Baiga culture. Here are a few : The Baiga people form a very ancient ethnic group of approximately 300,000 souls whose DNA is close to that of the Australian Aborigines. They are mainly found in Madhya Pradesh but also in Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Sometimes nicknamed "The Sons of Nature", because of their proximity to it, they once inhabited the forest that nourished them. They then became farmers practicing slash and burn agriculture. They do not plow because their beliefs lead them to think that one does not have the right to skin Mother Earth. Over time they refined their knowledge of plants. Their remedies and poisons, but also their diagnostics are reputed for excellence, so they are considered as very effective homeopaths. Inspired in the first place by nature and inked only on women (men do not even have the right to attend a tattoo session), Baiga tattoos have three major reasons for being. First, they clearly indicate their clan identity. Secondly, the pain caused would prepare women for the pain and the vagaries of the world (childbirth, work, etc). Third, only tattoos accompany the deceased in the afterlife, the ultimate memory of this world. But a few other reasons are added: body beautification, social status. The Baigas also believe that this practice works in the same way as acupuncture and these "bites" would greatly improve some functions of the human body. Finally, another belief encourages women to be tattooed here and now : if they did not do it, once in heaven, God would energetically take care of it with the help of a big iron bar. Baiga women do not tattoo each other. They usually involve women - tattooers from other social groups, mainly from the Ojha, Dewar or Bad(n)i groups (such as Shanti Bai). The generic term used to refer to these inking professionals is "Godharins" ("Godhna" meaning "tattoo" in Hindi.)

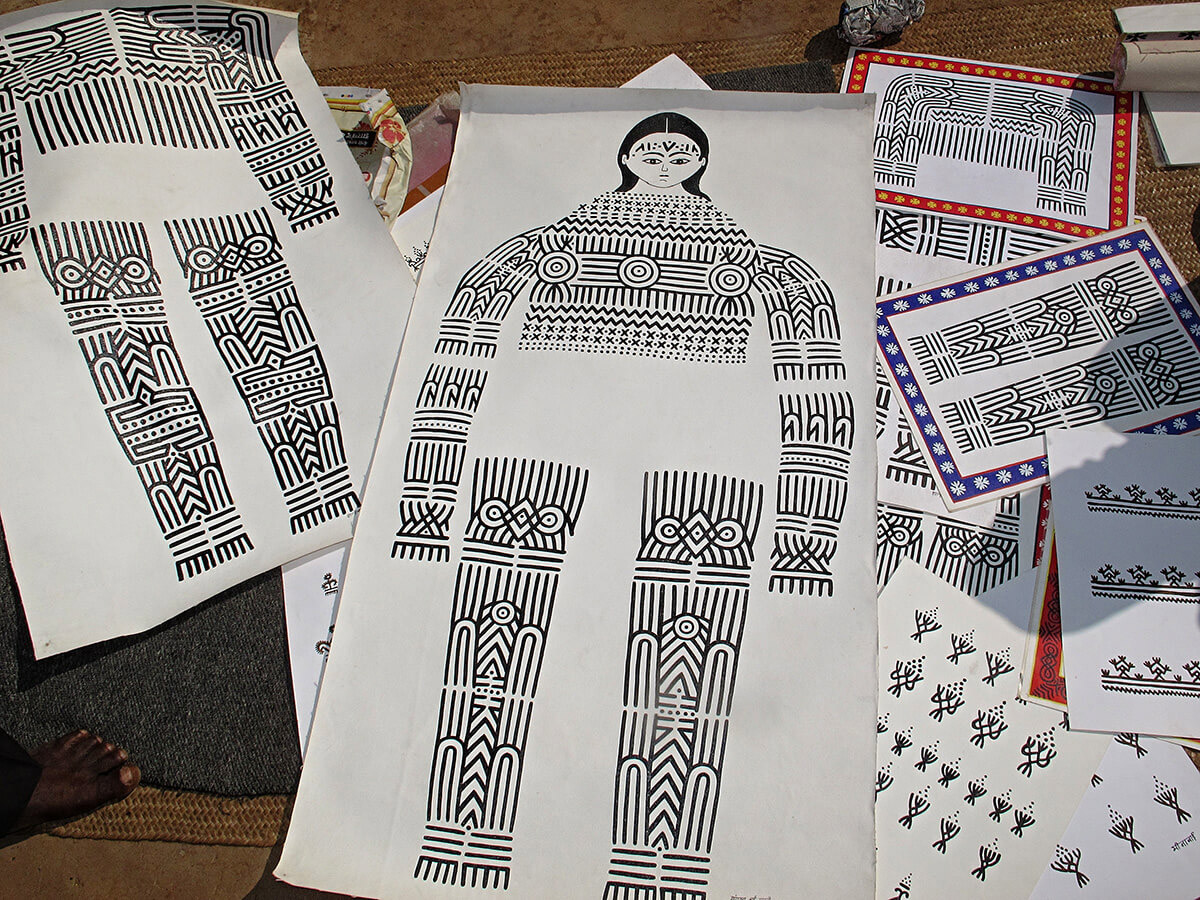

The patterns are not chosen at random. The different parts of the body receive their specific patterns at a specific moment in the life of the women : the first tattoo is the one made to the forehead. This is the "V" plus some vertical dots and lines. This happens around the age of 7 to 8 years and can be done up to 16 because beyond that the forehead tattoos bleed too much, rejecting the pigments. Then comes the back around the age of 16. After the forehead and the back and according to the different Baiga groups, before or after marriage, the legs, thighs, arms, throat and finally the chest will be tattooed. It will take 20 to 25 years for the whole body (except the buttocks and belly) to be tattooed. The recurring patterns, very geometric and stylized will be linked to nature (grains, bull's eyes, beehive, peacocks, hens, flowers, trees, etc.) and the elements (mountains, fire, sun, moon, etc.). But today, as in most tribal cultures, such practices cease with the new generations. School and television are the two main factors of this slow but sure disappearance. Moreover, these body marks are too ostracizing for this youth from ethnic groups at the bottom of the social scale, and who are just waiting to blend into the mold of the majority culture.

A foreigner likes to be tattooed by the Baigas.

To finish with that story, and come back to my ankle, following this last meeting with Shanti Bai, I bet more on a change of care than on the incantations of the shaman in tank top. After cleaning my tattoo with water, in the morning I applied the local recipe, turmeric and mustard oil, in the evening I applied a mixture of Homéoplasmine (a basic french skin care cream) mixed with a few drops of essential oil of lavender, recipe that I usually use for all my tattoos. After this last tattoo rejected two successive scabs of ink, I could finally walk pretty much normally. Due to a lack of time and a broken camera, I had to leave the area to reach Raipur, further east, the capital of Chhattisgarh, an urban ugliness. Fifteen days were needed to collect my Canon, and in that time I took advantage of a camera loan to go deeper into the state of Chhattisgarh to encounter another fascinating tattoo culture: the RAMNAMI. Adventure that I retrace in another article for INKERS. TRANSLATION Newspaper article, with a few mistakes from Dr. Chourasia: A Frenchman had to overcome the pain of the needle to get a tattoo, on both feet, one of the customs of the Baigas culture. This Frenchman named Stephane visited several parts of the country, but the culture of Dindori and its tattoo art impressed him. He now thinks of writing a book on the Baigas. For the past week, Stéphane has been surveying the villages to witness the wide variety of local traditions and to collect informations on the lifestyle of the Baigas. Stephane told us that the tradition of tattooing made him travel through Himachal Pradesh, Orissa, Bengal, Assam, Arunachal and other states. But for him, the most interesting tattoo culture is the one found in the Baiga culture of Dindori. It is usually women who perform tattooing by hand. Pain in a surprising tradition. As soon as Stéphane was tattooed by Shanti Bai from Lalpur, he felt an unbearable pain. Despite this, he approves and respects this most surprising tradition. "In the Baiga community, there is this well-known legend that women who do not get tattooed suffer more misfortune after their death. This is still believed today. The culture of tattooing in the Baigas continues. A young Frenchman interested in it had his feet tattooed. " Doctor Vijay Chourasya