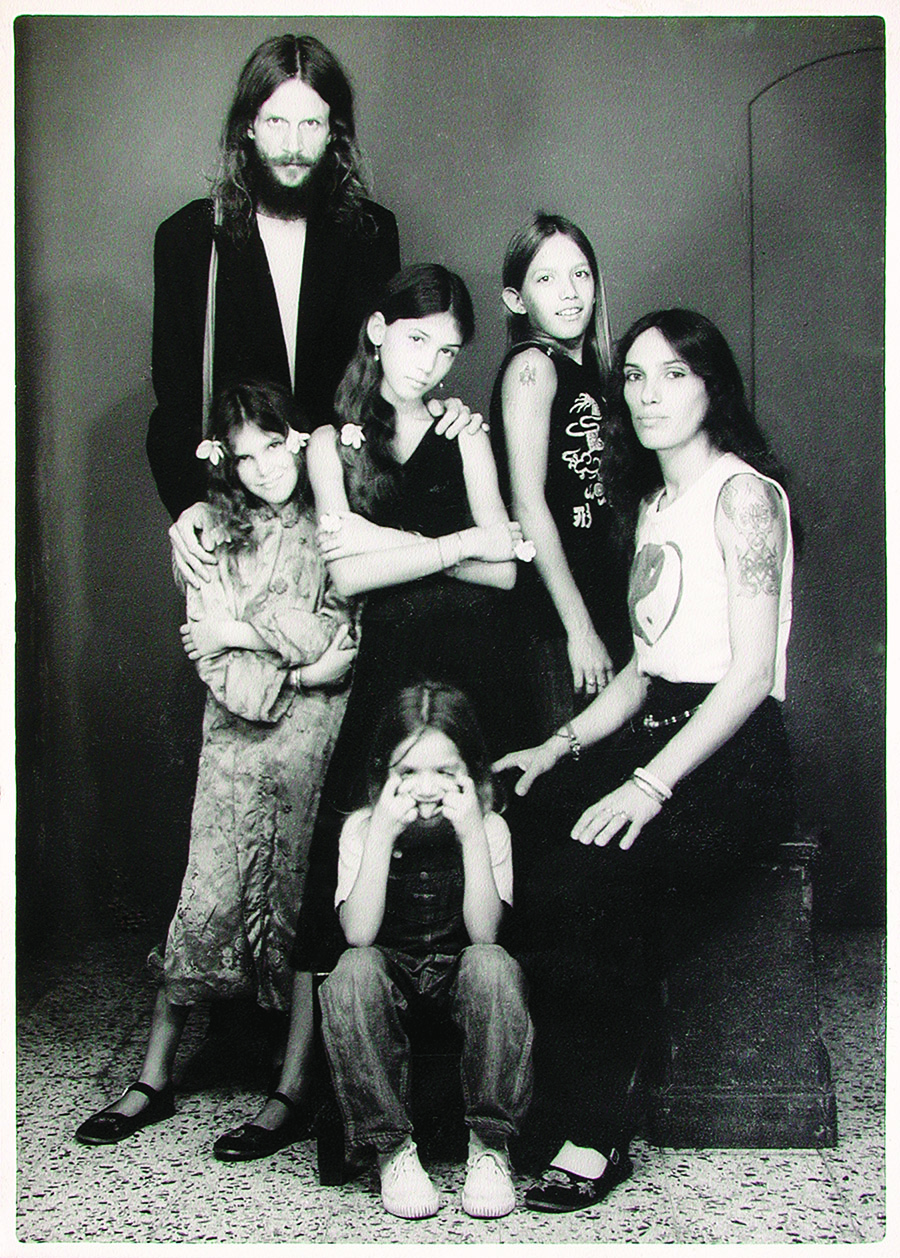

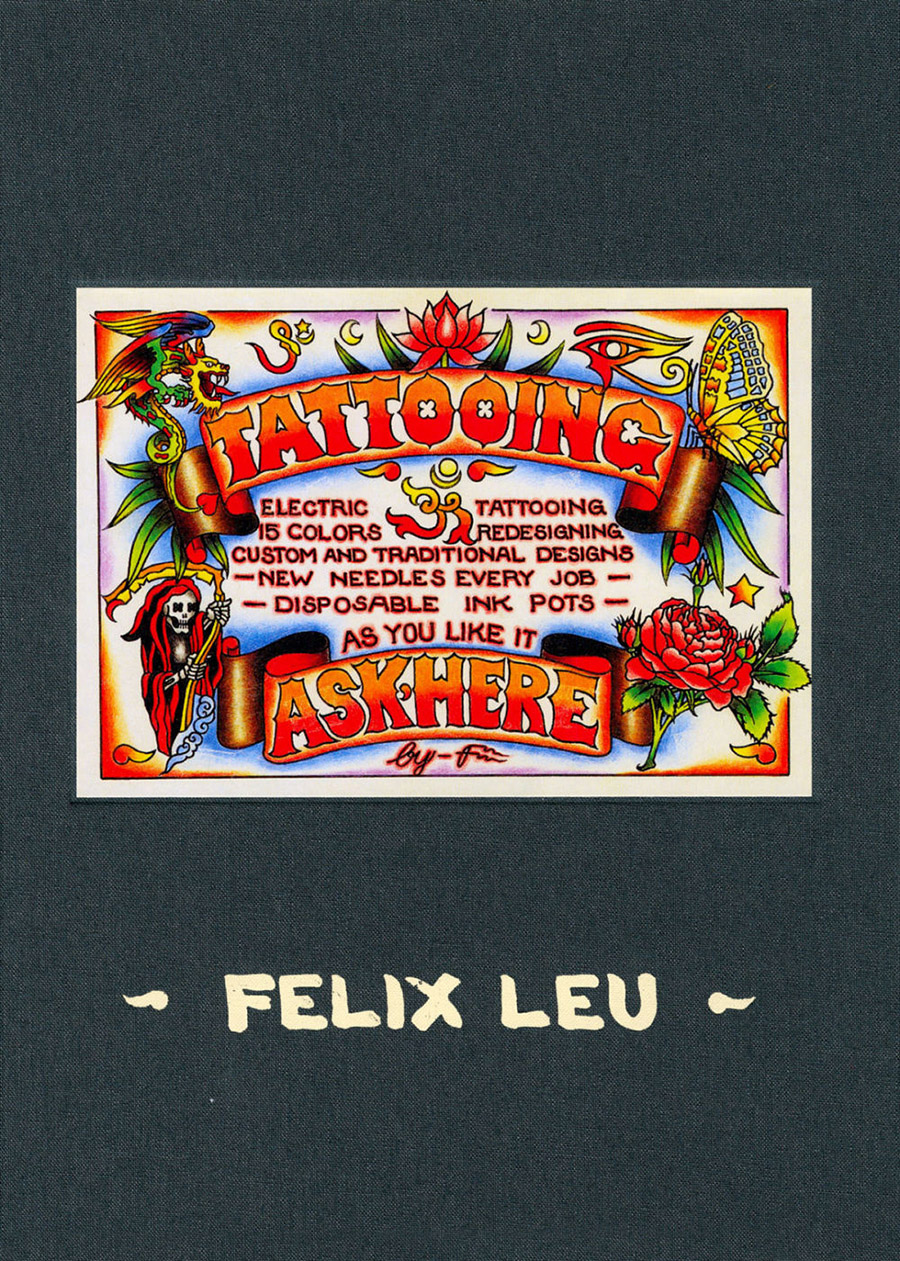

With the publication of the book “Tattooing, ask here” dedicated to Swiss tattooer Felix Leu, we grabbed the opportunity to interview Loretta Leu and get back together on some of the pages of the incredible history that built these tattoo legends. With the publication of the book “Tattooing, ask here” dedicated to Swiss tattooer Felix Leu, we grabbed the opportunity to interview Loretta Leu and get back together on some of the pages of the incredible history that built these tattoo legends.

How did the idea of making this book come about?

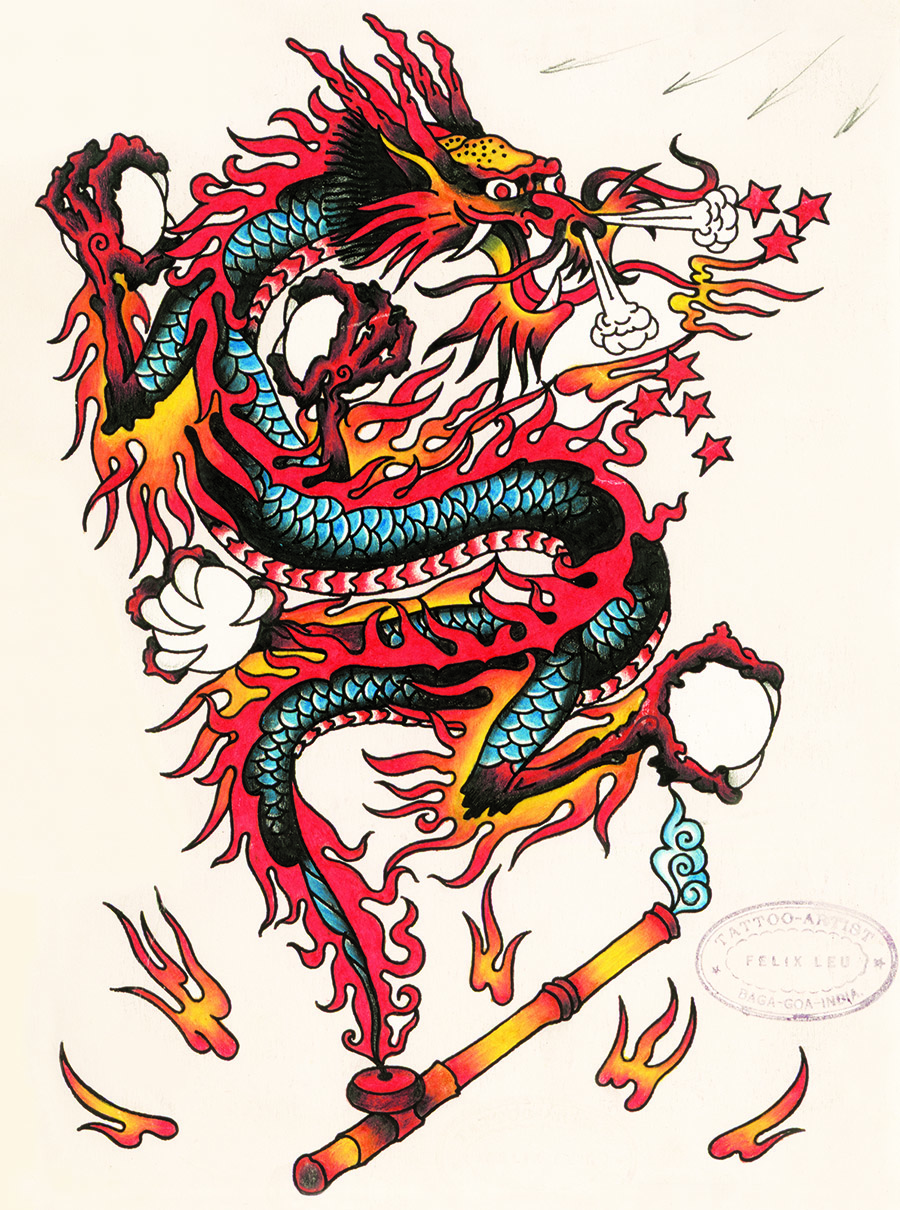

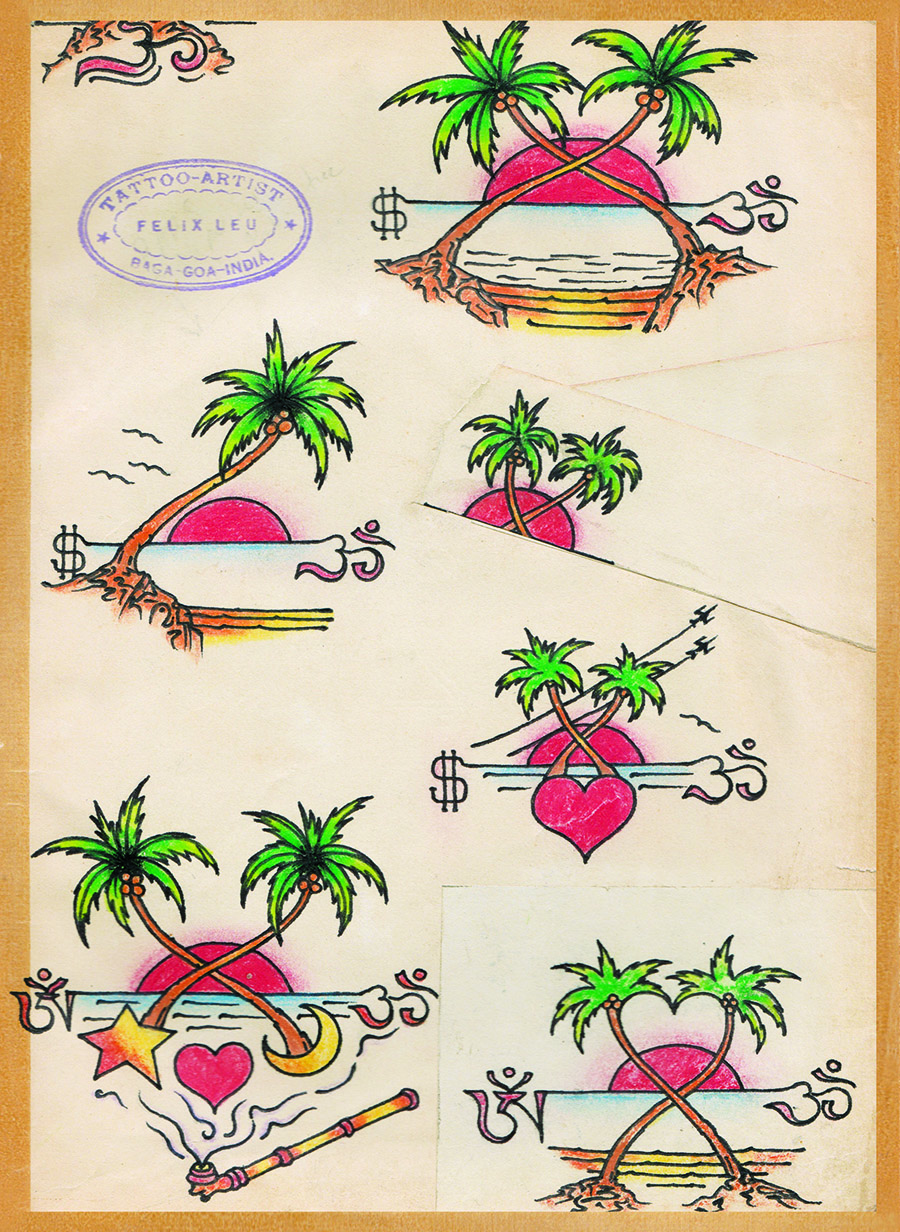

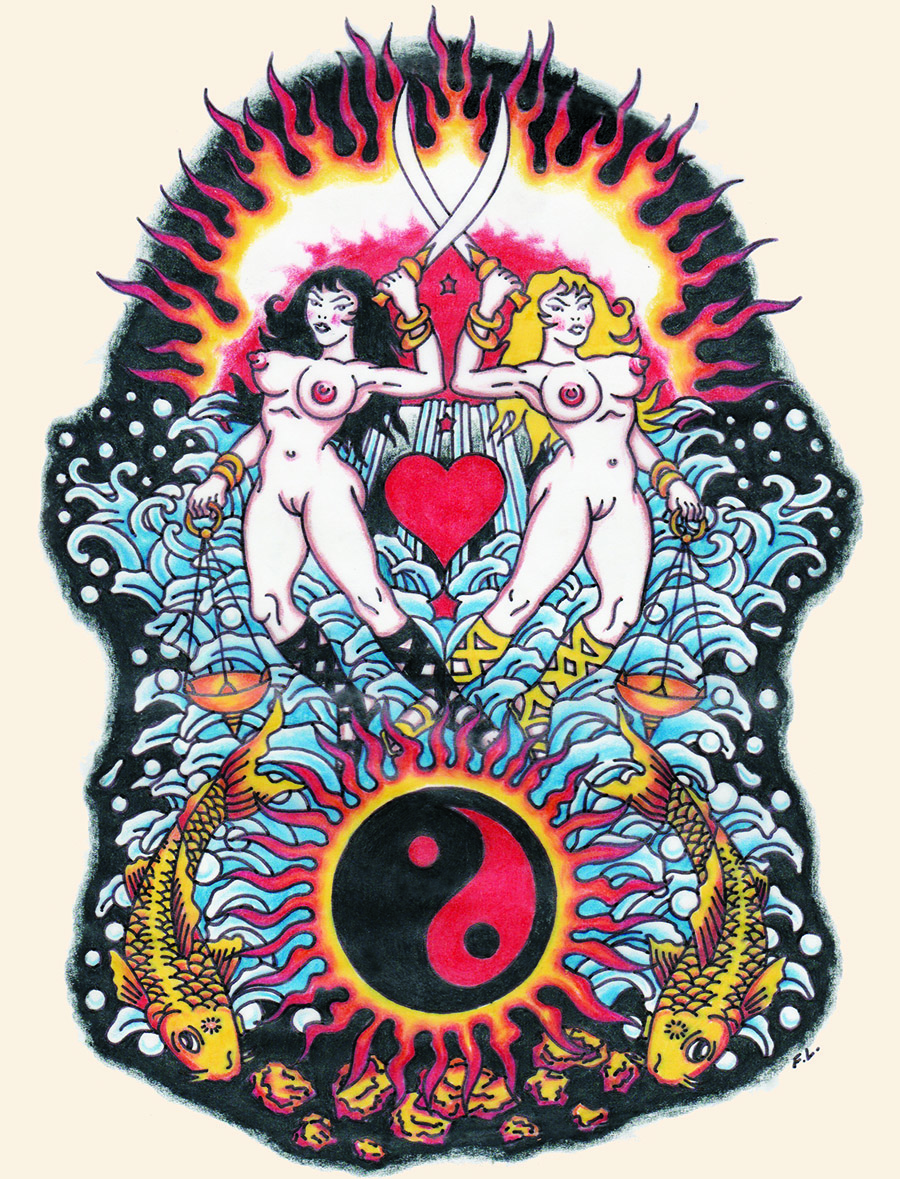

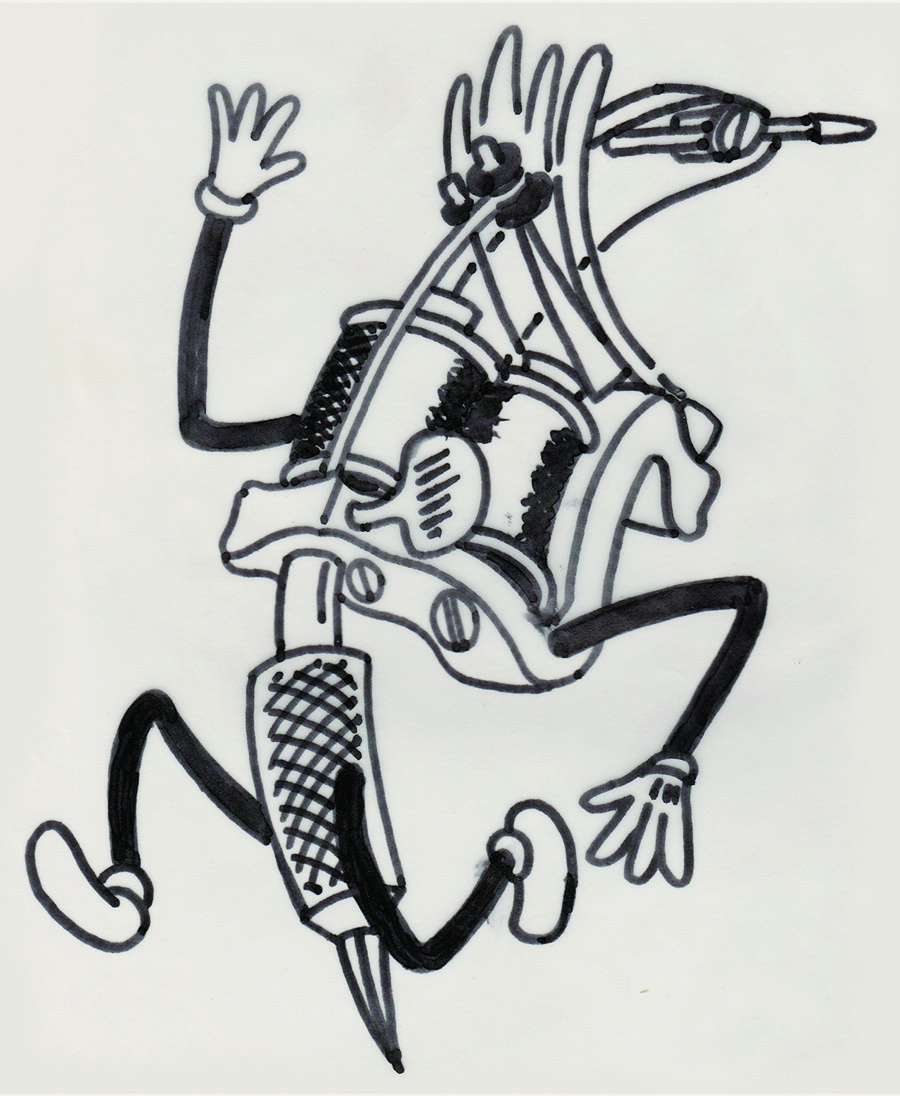

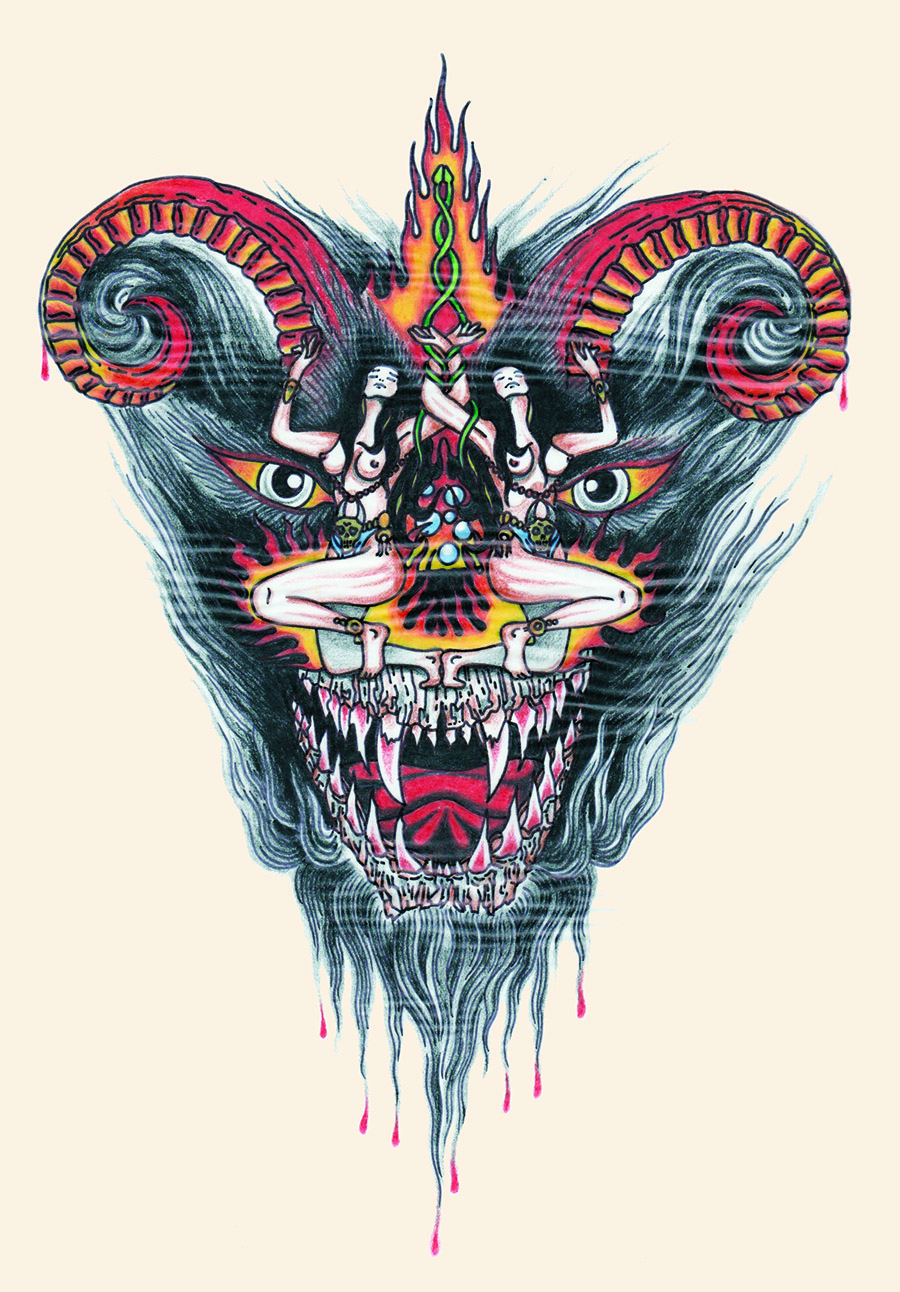

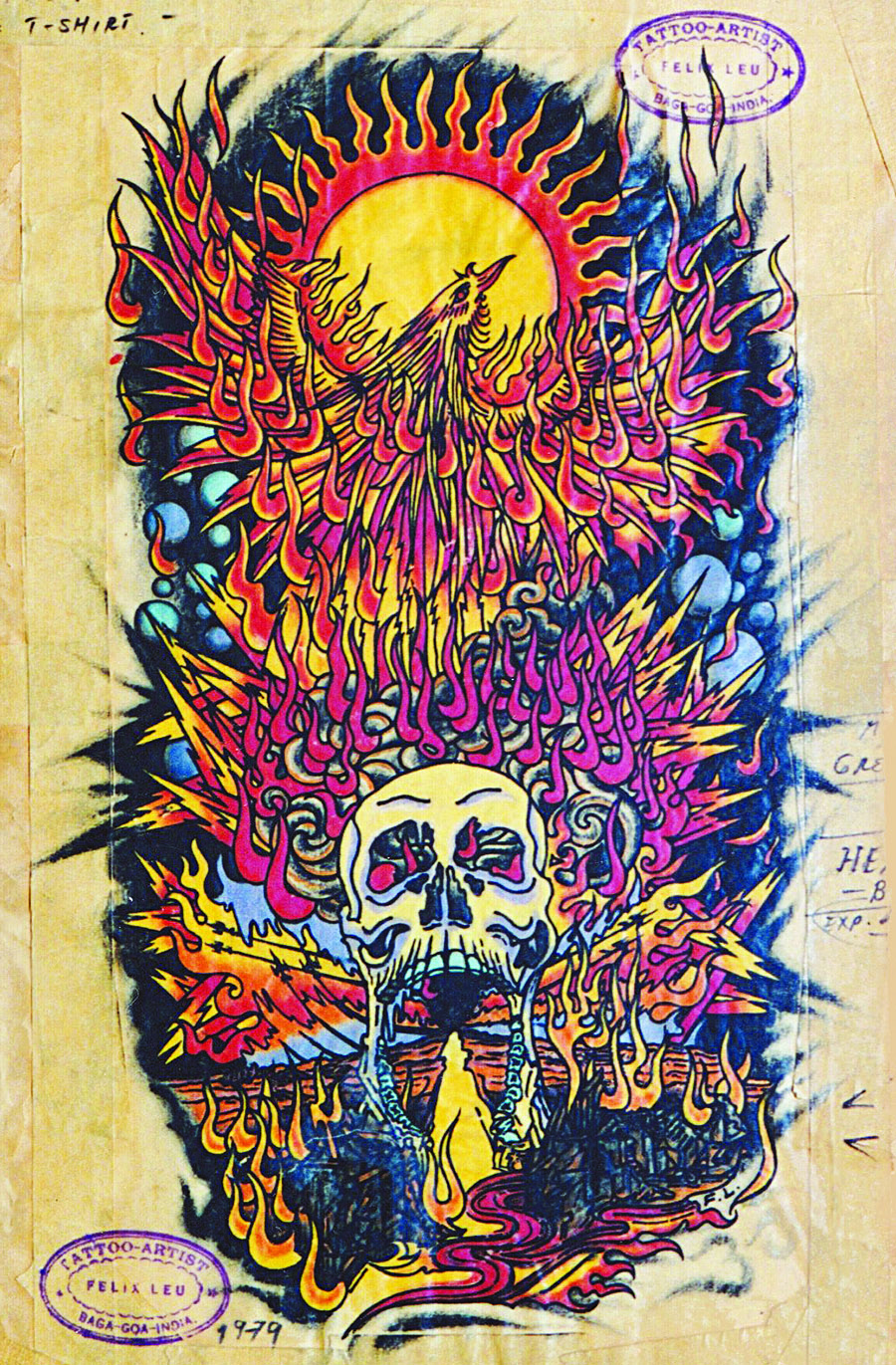

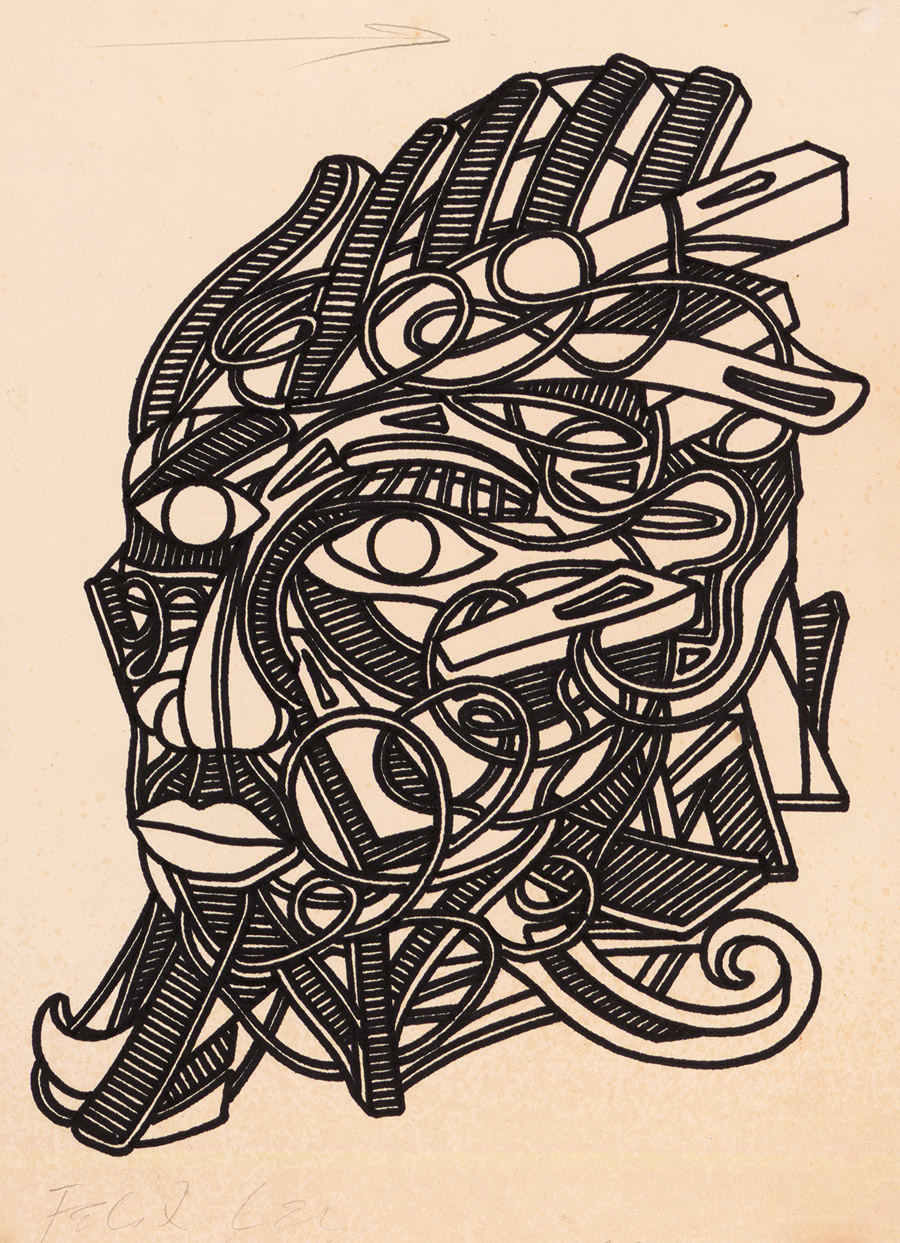

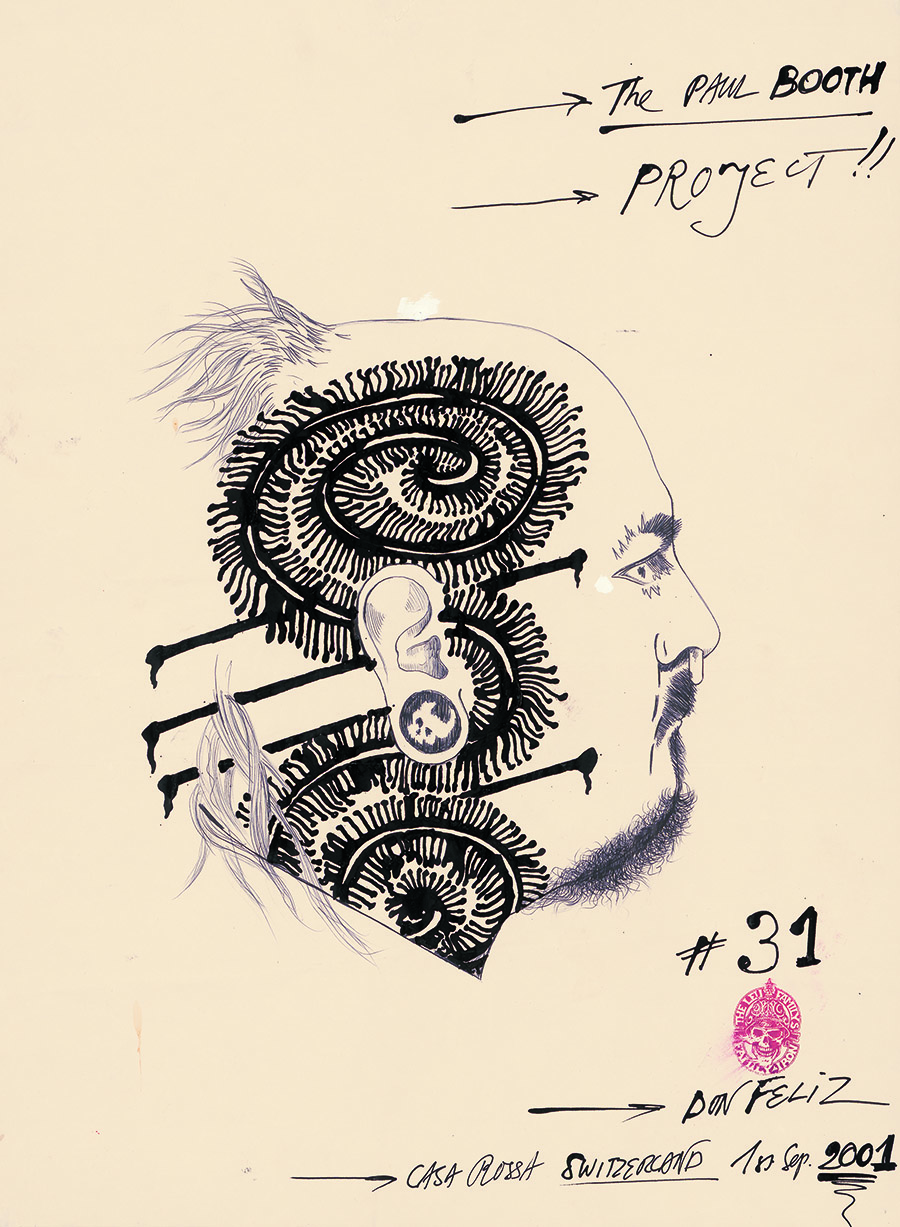

I had started to collect some of Felix’s earlier flash drawings, just knowing that one day I should do something with them. I looked through our old flash books; we didn’t keep his drawings separate, they were mixed in with all our other flash. It took me some time to collect all these images. Then, my daughter Aia Leu came to visit and saw what I was collecting. She said: “Why don’t I help you and we do it again, make a book together and I’ll publish it.” It is really thanks to her enthusiasm and hard work that this project came to life now. The idea from the beginning was to include Felix’s tattoo designs, photos, also an early drawing like the one from 1977 which shows fantastic line work for a future tattooer. And part of the story before his tattoo life. Because tattooing didn’t come into our life until we were 33. We had a whole life before that. When tattooing came to us, we already had four children and had travelled a lot; we had done many things to support ourselves, make jewellery, batiks and other different jobs of that kind. Whatever we could figure out to survive in fact. And then tattooing came into our life; I’ve put the story in the book. It’s even in Felix’s own words because we decided to quote some of the interviews that he did.

Why was it important to tell Felix’s story?

I have at home a whole collection of books of tattooers from the early 20th century. I’ve always found it interesting to read about Charlie Wagner, Amund Dietzel, George Burchett and all these people, to know how tattooing was back then. Today, many young people and artists say to me: “You come from this wonderful tattoo family…” but, they don’t actually know much about us, because very little has been published over the years. So that was the idea behind the book : to present Felix Leu so that younger artists know something about him. Older ones like myself could find it fun to read too, because they might have had similar experiences. And if in 50 years’ time somebody is researching about tattooing in those early years, then they’ll find a book about Felix and what he did.

You said you were initially looking for earlier flash, did Felix draw a lot even at the start of his tattoo career?

Yes, in the beginning it was one of the things that brought people to us. He drew custom flash for people in a period when not many tattooers were doing that; most were doing traditional “off the wall” flash. But Felix was an artist before he was a tattooer so he could offer this custom service. Somebody would come in with a sketch - I’ve put one example of this in the book - and Felix was able to draw a better version for him. I don’t have much of his later flash. Most of the ones in the book are earlier ones, from the 80’s to early 90’s. The last part of his tattoo years Felix did a lot of freehand work where he worked directly on the skin, that’s why there aren’t many sketches on paper. He would just draw some main power lines on the skin with a pen and then tattoo directly with the machine.

Flash was also a way to advertise.

Yes. He said from the beginning: “You can be the best artist in the world, but if you don’t put it out there, nobody knows”. Same for Filip. His reputation has grown by now, by word of mouth but also because we do still send out photos of his tattoos and artwork to the magazines and books. Advertising in that way is important if you do something. Otherwise, you can be great, but if nobody knows you’re there and what you’re doing, this doesn’t help you.

The book is a great opportunity to meet a man, determined at a very early age to enjoy life and the freedom of the time…

Absolutely, that was Felix 100%. “We only live once”, he liked to say : “We only get one time!”.

What was the trigger that made him leave his parent’s house at 16 ?

Well, he didn’t agree with his father’s mind-set. He was a Swiss architect, conventional, bourgeois, well respected and all that. Felix was quite proud of the fact that in his rebellion he got kicked out of many schools - maybe 10 - by the time he left home. The last one was even a Rudolf Steiner school, which was supposed to be very alternative and open-minded…

What was the reason?

He told me that in one of them he punched one of the teachers in the face (laughs). But really the trigger for Felix to leave home was when somebody gave him a copy of Jack Kerouac’s book On the Road. He totally agreed with the message : “Go out there, enjoy your life, explore and meet a lot of women and have a good time” (laughs). Also, he had grown up with his father but his mother was a Swiss artist : Eva Aeppli, who was living in Paris at the time and had married Jean Tinguely, a Swiss sculptor. Felix visited them a few times when he was 14 or 15. Even though they weren’t famous yet and living a very poor artist’s life in a studio in the Montparnasse area, I think he very much appreciated their lifestyle. It inspired him, he could see there was another way.

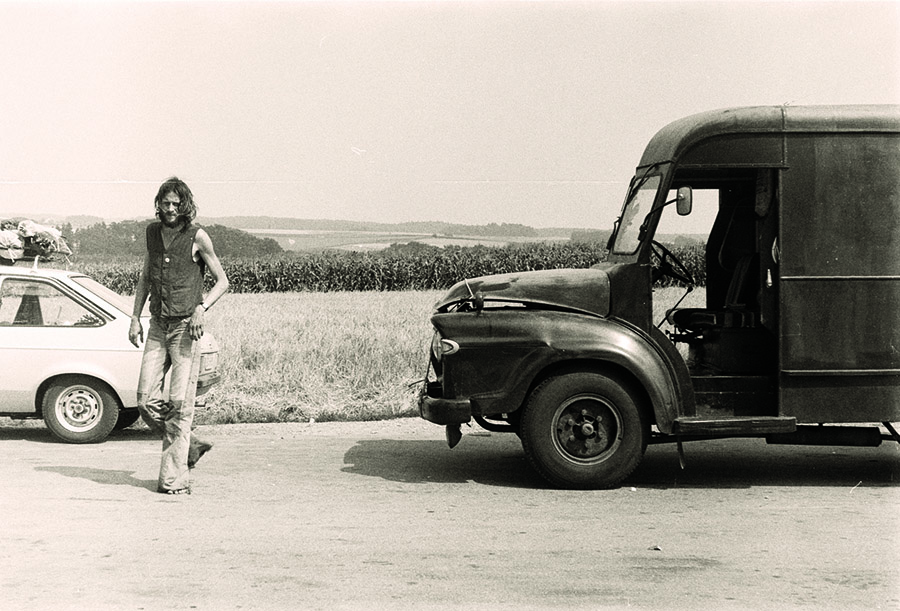

Then he spent 4 years living a very beatnik lifestyle.

He told me that he had quite an education in Paris, because for some time he was living on the streets, sleeping under the bridges next to the clochards. They taught him some tricks about how to survive outside. He said that his first job was as a beggar. To him this was a very honourable profession if you did it properly, without bothering people. Don’t tell them your story, don’t bore them with your problems, just ask them! If they have money maybe they’ll give you some, or maybe not. I know he spent some time like that, buying bread, cheese, and a bottle of the cheapest wine once he had enough change, before falling asleep somewhere, under the bridges…

Did he have any connections to help him ?

His mother couldn’t help very much because she didn’t have anything either. He was kind of on his own. The second job that he learnt from the street people was to draw on the sidewalks. He would get a postcard of a famous painting that people would easily recognise and copy it on the sidewalk. It’s also a good profession, except when it rains, right? (laughs). He told me that another way in which he learnt to survive was, because he was good looking, making friends with young American female tourists, they always had a hotel room. That night he wouldn’t sleep in the streets.

How important were these 4 years for his personal development do you think ?

They gave him a lot of the courage and strength he had throughout our life, to travel and do the things we did. He was not afraid. You can choose to starve and not have food when you’re on your own, but it becomes a different story when you have children. You have to find a way. Strangely enough, he kept something from his early background, a certain way of doing things which was very Swiss-German like : whenever he set his mind to something, he did it really well. He didn’t do things half way. Whatever he did, he went for it 100%.

You meet him in New-York in 1965, what did he look like?

I was invited by an ex-boyfriend to the Jewish Museum for the opening of an exhibition of two sculptors : Tinguely and Nicolas Schöffer. It was a big gala where everyone was very well dressed, there were art collectors, champagne, etc. I walked around, heading to the buffet and as I entered the room I saw this tall, skinny guy, dressed in a dark red velvet jacket, with a white t-shirt, black skinny jeans and motorcycle boots, he had longish hair… He looked like an artist. We both looked at each other and it was like a flash. I thought : “Oh, he looks interesting…” A little bit later I was sitting on a bench with my ex-boyfriend and we were having an argument. Soon he got up and left, leaving me crying. Behind the bench there was a pillar and suddenly Felix appeared from behind it, smiling, and asked me: “Can I buy you a drink ?” That’s how we met. We went around the museum, he told me he was assisting his step-father, Tinguely, for the exhibition and asked me if I wanted to see upstairs, where it was closed to the public. I said ok and we went up. It was all dark and there were just a few things displayed. He tried to kiss me! I said: “Hey! We just met!” (laughs). But we really liked each other and we managed to meet again the next day. From then on we were pretty much together all the time. I knew within a few days that this was the most interesting person I’d ever met and I wanted to be with him. A few months later he said that he was going to Morocco and asked me if I wanted to come. I said yes. That’s how our story started.

As you said earlier you had a whole life before tattooing. What happened during those 13 years?

We tried many different things. Survival was not always easy. When we lived in cities, we lived in squats. In London, where my mother was, we stayed with her a few times. Felix would go to art schools at night to use the facilities, because they were also open to non-students. He already knew how to do silkscreens and printed about 50 copies of a folio of mandala designs he had drawn. Then I would go to small alternative book-shops and try to sell these. Felix learned how to make jewellery too. Me, I didn’t have a work permit because I was there as a tourist, so I did some modelling in an art school ; they would pay in cash. I worked also for some people who had gambling tables in Soho and other parts of London. They hired young women like me to run these games; we just had to set up the cards and take the money. It was clubs with people dancing and drinking. I never had any trouble, but that was a very good job, very well paid! And for some of these years we lived in the countryside in Formentera and Ibiza, where life was cheap at the time.

Was it Felix intention to be an artist ?

He didn’t like the art world. He had experienced it with his mother and Tinguely. He didn’t want to be part of it, to deal with galleries or art dealers. He was an artist, 100%, but he didn’t believe in compromise, in being nice to somebody he didn't like, just in the hope that they would buy his art. It was hypocrisy. That’s what he liked about tattooing so much : it was direct. There was nobody in the middle, just you and the client. A clean transaction. And you could do it anywhere.

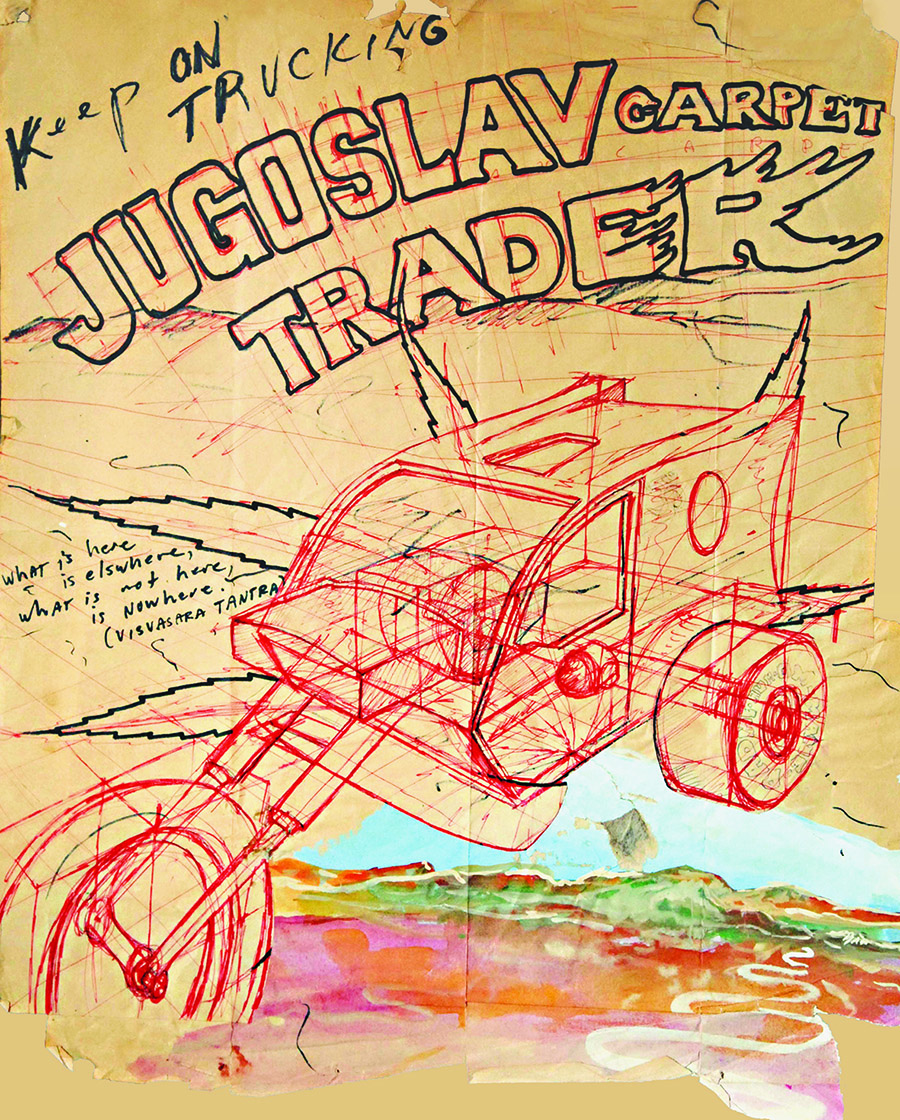

Then, Felix is asked by your mother, who had a boutique in London, to drive her in his van to the Kosovo province of Yugoslavia where she wanted to buy hand embroideries and Kilim carpets. And there, Felix had this revelation about tattooing. How did you look at tattooing at the time?

It was not part of my consciousness, I had never met anybody who was tattooed. The same was true for Felix. The only tattoos we had noticed were the ones we saw in photographs of tribal people in the National Geographic Magazine. We always thought they were beautiful, but we knew nothing about Western tattooing.

It needed a lot of perspicacity for someone who hadn’t any relationship to tattooing to understand that here was an opportunity.

Felix understood immediately. If in this little village where they stopped, these young men came to him waving money saying : “Tattoo, tattoo, tattoo” simply by looking at the images that his co-driver, our friend Robbie, had on his arms - a geisha done in Scotland, and a Scottish piper done in Hong-Kong -, it would happen everywhere. He was smart. He picked up immediately that it was a good one. And the fact that he was already an artist, and so was I, gave us an advantage. Then Felix started to actually look at tattoos on the arms of truck drivers on their way back to England, when they stopped for gas and to drink a coffee. It was all old style traditional designs. He thought : “I can do that. I can do even better artistically. I just have to learn how to do it technically”.

What was your reaction when he came back and told you that your future was going to be in tattooing?

I don’t remember, but during our whole life together I had faith in him. I was glad he was figuring it out because I was busy taking care of the kids. He was always the one finding solutions to our problems : “Let’s do this next, let’s go there”. “Ok”, I’d say. That’s just what was happening next. I don’t remember ever having any doubts.

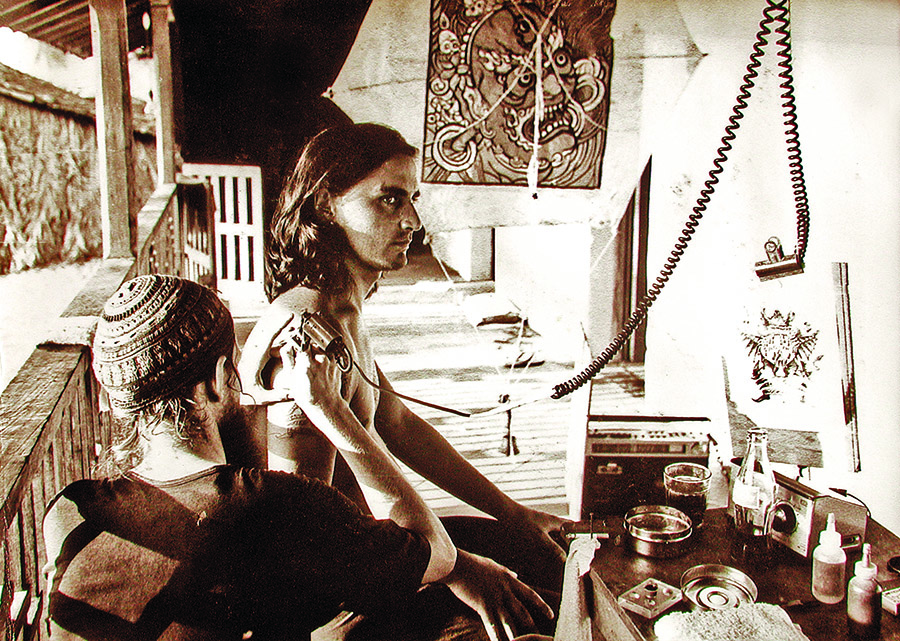

1978 is a crucial year in your life : Felix has the revelation about tattooing in Yugoslavia ; he learns the basics of tattooing with Jock, an old-timer in London who accepted to teach him and then, after 6 months of “apprenticeship”, all the family leaves, Felix with a bit of a material to start tattooing, to Goa, India. Why that fast and why that far?

First of all, life was very cheap there, and it was also a good place for kids to grow up in. But the main reason was that Goa had a steady stream of travellers passing through it, Westerners who would come there for 2 weeks, one month… people like us. So Felix thought that was a good place to go and tattoo. We didn’t have a lot of work in the beginning, maybe one or two tattoos a week. But because life was cheap - we could even afford two maids in this big 10-room house we rented - and with some money we had saved in Europe we knew that we could last for a few years. There were just a few tattooers there at the time. We became friends with Gippi Rondinella from Rome and Paco el Vasco, a nomadic tattooer. There was also an Indian tattooer, Soma, who worked in the market in the town of Mapsa and in the weekly hippie flea market.

How could you be sure that this stream of people would become a clientele?

Because of that village in Yugoslavia, come on! It’s true that tattooing was not so popular with hippies until Janis Joplin got her bracelet and little heart from Lyle (Tuttle, tattooer from San Francisco). It was not a big thing in the hippie scene. There were not so many people tattooed when we arrived. But there were travellers, freaks, which is a bigger name for the whole thing. “Freaks” includes everyone who thinks differently, people who don’t follow the mainstream; hippies is a certain niche label. Because we were the same as our clients in a way, it worked!

Felix didn’t have any tattoo culture and therefore came to it without any preconception. He was able to offer custom tattoos, using contemporary references picked up from his era.

Felix went for what people were asking for and he was able to draw it. Most of the flash that I found is fairly representative of what people asked for in Goa : butterflies, Goa scenes, eagles, Om and peace signs, dope leaves, Ganesh, Buddha… also what you see in the transfers shown on the inside covers of the book. It was their ideas, but Felix’s way, right ? We also had a catalogue of flash sheets from Spaulding and Rogers, but the images were a very small size, so it was Filip’s first tattoo-related job to enlarge them by hand using the grid system.

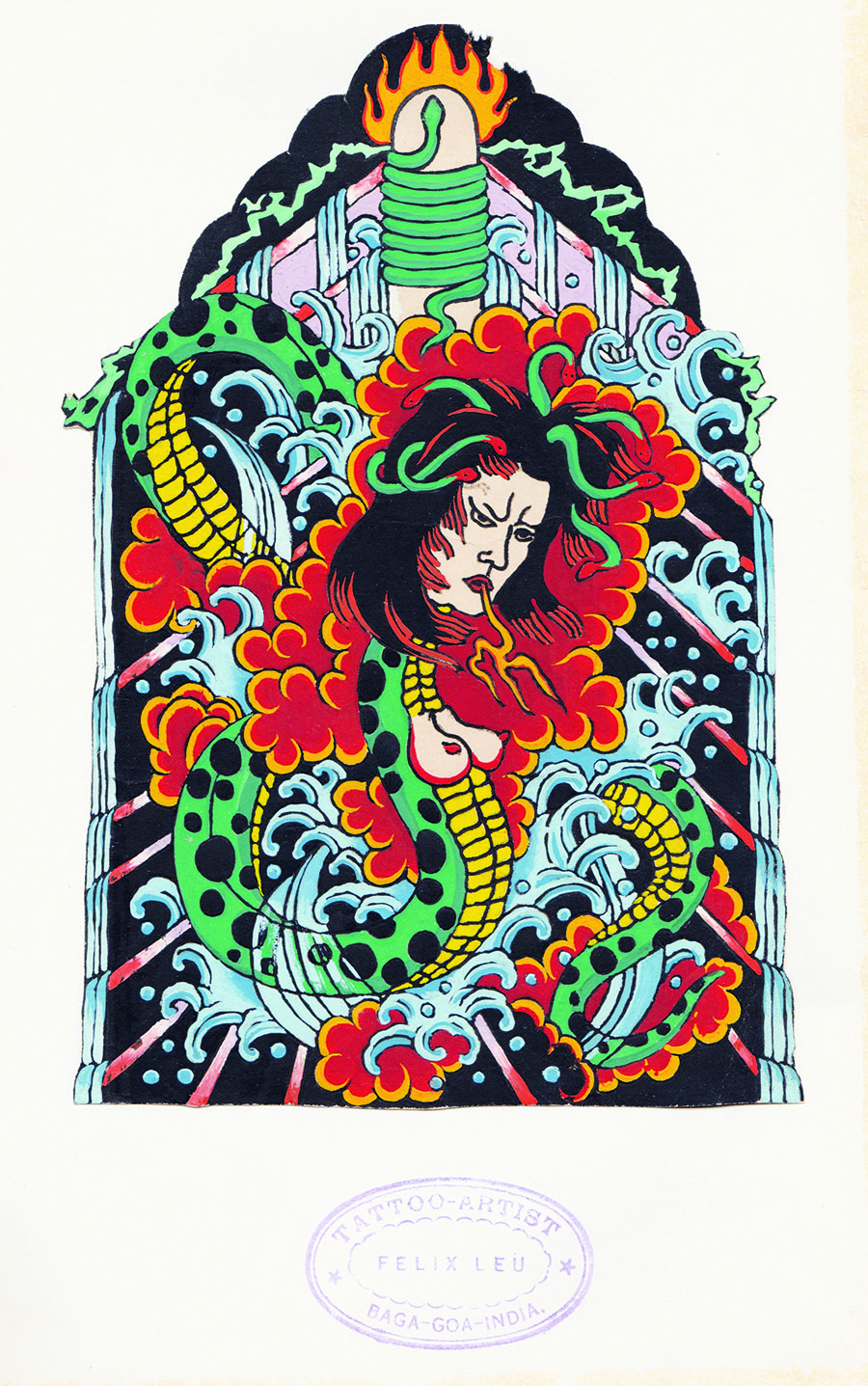

What were Felix’s graphic inspirations?

He was a huge admirer of Salvador Dali. He thought he was really a good painter and somebody who worked really hard at it. He liked comics, all the underground artists like Robert Crumb, also the artists who did the psychedelic posters in San Francisco in the 60’s like Rick Griffin or Mouse and Kelley who did artworks for The Greatful Dead, etc. In 1967, Felix was in San Francisco for a few months during the Summer of Love, and that definitely had an influence on him. He also liked Peter Max, very brightly coloured art which combines fine art with a cartoony style. Later on, he really liked Robert Williams, who did that famous record cover for Guns N’ Roses. He had also a lot of influence from the East, inspired by Indian and eastern forms and symbols.

You left India after almost three years, why?

For a couple of reasons : we weren’t getting enough work and our money was starting to run down. On top of that one day we had our remaining funds stolen and we were obliged to ask for repatriation to Switzerland by the consulate.

What happened once you were back in Switzerland ?

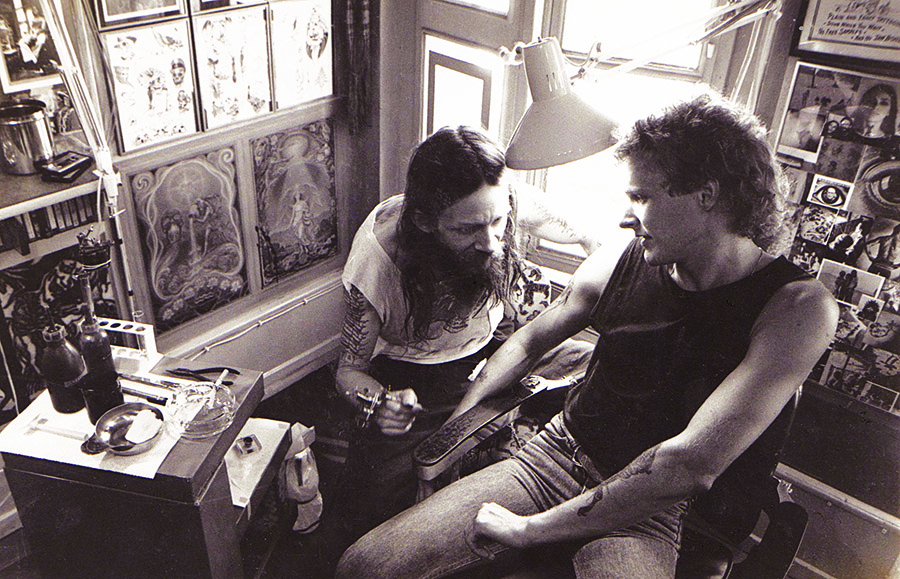

We arrived in Lausanne with absolutely no money. The first few months, the State helped us. They gave us a place to live in a little hotel in the middle of the city. We said the government: “We need a place to live, but we don’t need money to live. We’ll tattoo immediately”. And that was true, we were tattooing on the second day already. Felix immediately drew up some flyers and went to a photocopy place to print up a bunch. It was summer time and there was a public place where a lot of young people would hang out. We stationed ourselves there and when someone with a tattoo passed by, we would go and say hi, said we were at the hotel over there, that we had a lot of designs and everybody was welcome to come by and see (laughs). But after two days the manager of the hotel came upstairs and said it was not possible for us to tattoo. He didn’t mind the work… but he minded all the punks and everybody coming up and down the stairs (laughs)! Then the authorities put us in another hotel; here nobody minded as the hotel was full of ex-alcoholics, ex-this and that. We told them again: “If you give us a room where we can tattoo we won’t need any money from you”. They gave us three rooms this time: one for me and Felix, one for the kids, and one for tattooing.

What was the situation regarding tattooing in Switzerland at the time?

There was no federal law, it was controlled by the Cantonal Doctor of each Canton. Tattooing was only tolerated in the Canton of Vaud (where Lausanne is), and Saint-Gallen. There was only one tattoo shop in Lausanne. It was an ok shop with two guys working in it but they didn’t do custom work, only flash off of a sheet. At the time, most Swiss people who wanted to get tattooed would go to Paris, to Bruno - he was famous at the time - or to Amsterdam to Henk (Schiffmacher). Those were the options from Switzerland. That’s part of the reason why our business grew quickly I think. There was a demand for it.

You stayed in the second hotel?

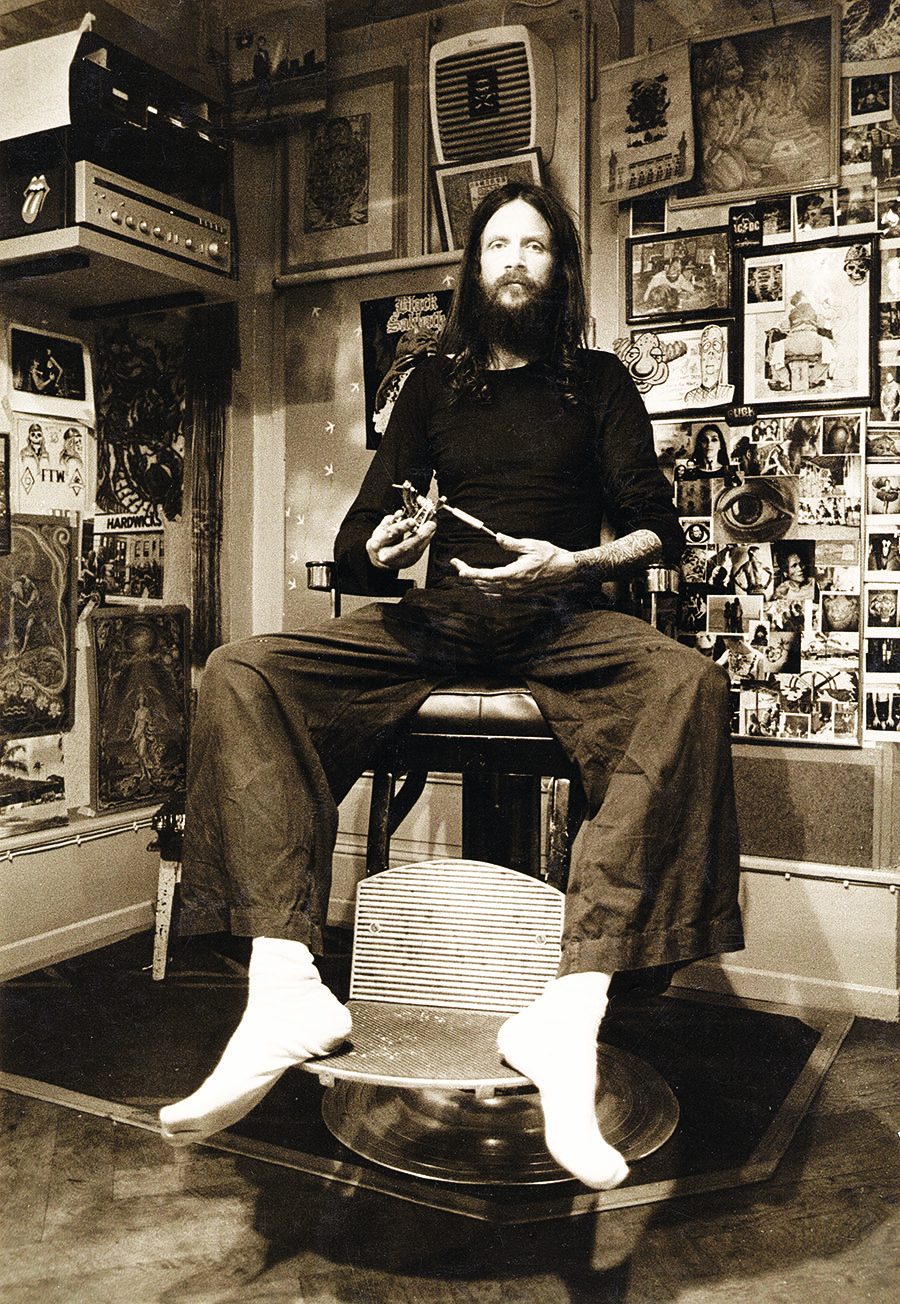

For a while, then we met some members of a bikers’ club which had its clubhouse just across the street from he hotel: The Warlords. Mao (tattooer running the oldest tattoo studio in Spain, in Madrid : Mao & Cathy) was the President of this motorcycle club and he was really nice to us. He said that if we wanted to, we could tattoo in the clubhouse. It was living day to day. Sometimes, when we arrived there for work I didn’t even have the money to pay for the paper towels or gloves we needed, so I would borrow money from the cash box of the club. I would go and buy the paper towels and the gloves, and then as soon as we did the first tattoo, I would put the money back. Mao knew about it. Then the government offered us the apartment on the Rue Centrale, where we stayed for 20 years. Nobody cared in this old building, once again filled with social cases, about the people coming up and down the stairs at night. Most of our customers would come when they had finished work, around 7 to 10pm and we would tattoo till 2 or 3am in the morning.

That was a big change, from being a tattooer on the road to an urban tattooer.

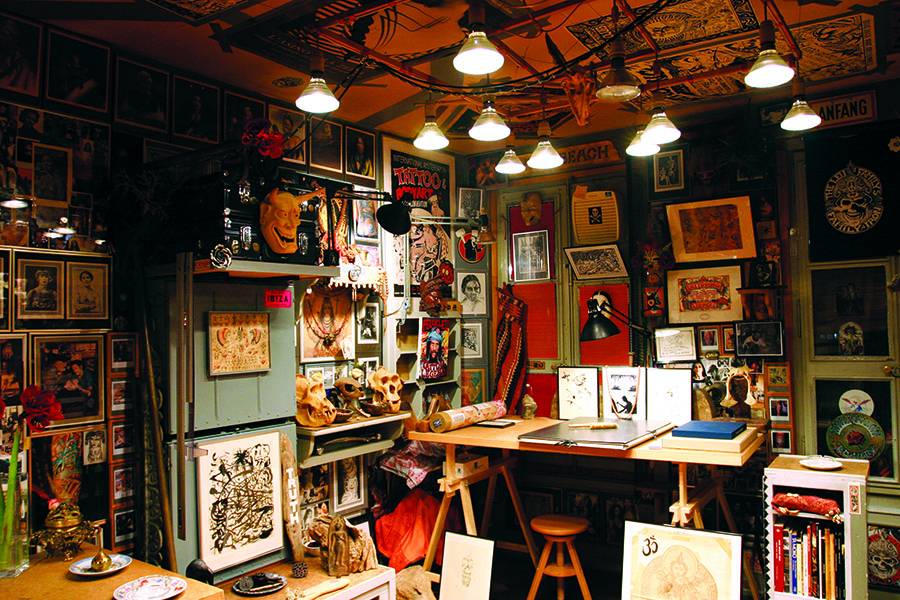

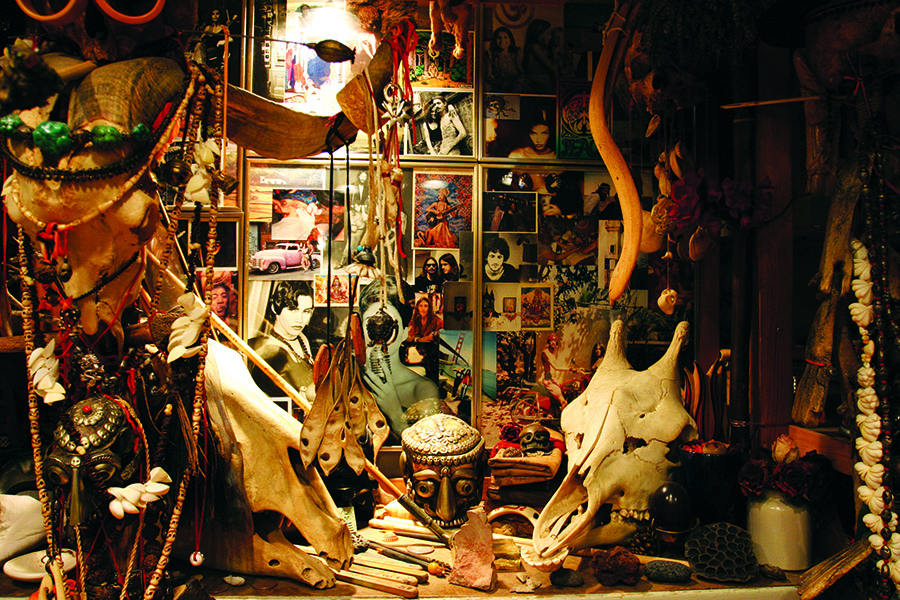

All the family helped but Felix was the driving force in the creation of this studio. Even though it was a small place, he tried to make it really interesting and really special. A place where people liked to come. Even though we never had any alcohol, people came to hang out sometimes, to look at the books, listen to rock’n’roll. It had a good vibe. It wasn’t like Switzerland (laughs), it was something else. We never had any bad things happen there, no fights; once Felix had to kick a guy out, but we never had anything stolen, even though the room was full of objects from around the world. People appreciated it as a special place.

Who were the people coming to you in Lausanne?

At first it was the bad boys, the ones who got into trouble all the time, young kids ; then there were a few punks, we had a lot of quite young clients in the beginning, including the next generation of beatniks and hippies from the “Centre Autonome” in Lausanne – a big squat that has since disappeared - then we started to get regular kinds of people: mechanics, teachers, cooks, doctors, nurses and so on. Other tattooers also came as our reputation spread…

Who were the tattooers Felix looked up to?

Some of the ones that we noticed as being exceptional when we started were Ed Hardy, Cliff Raven, Don Nolan, Robert Benedetti, Spider Webb. And after that many more.

Felix was doing custom work, how would he feed his inspiration?

Felix looked at books and other artists but mostly he relied on his own imagination. Already in the mid-80’s, Felix started experimenting with more psychedelic colours and shapes, free-handing a lot of his work. He drew a lot, every day, and he was a big reader - we never had a television. We didn’t even have a telephone for 10 years, people had to write for an appointment or they had to come and see us directly. Felix was a big believer in rock’n’roll and it was a constant in the studio. ZZ Top was one of his favourite bands. We discovered a lot of music when we came to Switzerland. Because of our travels some bands we had never heard before, like AC/DC, Motörhead... Then also his inspiration came from the things that the customers brought us and were asking for; a lot of it was connected to the artwork on vinyls, from artists like Frank Frazetta and Boris Vallejo. We adapted it to tattooing. Besides these influences Felix developed his own artwork.

Do you think that having worked close to Tinguely, who was a sculptor, had an influence on his sensibility to 3D art?

Absolutely. And not only 3D art. Tinguely was experimental in so many things, he was very avant-garde… Felix was definitely influenced in that direction, both by his mother’s and by Tinguely’s art.

The hippie movement had a lot to do with LSD and you said Felix was doing also a lot of psychedelic work. What place did drugs have in his creation?

It definitely was part of our lives. Felix was a confirmed marijuana smoker, until the day he died. LSD played a big part in our life at different times, especially in India. There is a series of three painting (titled respectively : “ LSD 25”, “Mescaline” and “Speed”) where he wanted very specifically to see what effect certain drugs had on his artistic state of mind. One of Felix’s favourite mottos for many years was : “Sex, drugs and rock’n’roll”. Three of the main things in life, the enjoyable things : “Sex- drugs-and-rock’n’roll”.

What would he think of the tattoo world today?

He was very intelligent and I think he would have accepted the changes. But he might also have regretted the loss of interest in books or knowledge, in the history of what came before. I’m sure he would be super impressed by how many fantastic artists there are today, the fact that many come to tattooing with an art background. But I think he would regret the loss of the outsider element. Because what attracted us to tattooing is not only the directness with your client but also this element, the circus heritage, something outside of normal society, the pirate and rebel thing. And that seems to be getting lost. Everybody’s trying to be normal. But things change. C’est la vie…. And life is wonderful! http://www.leufamilyiron.com https://seedpress.ie