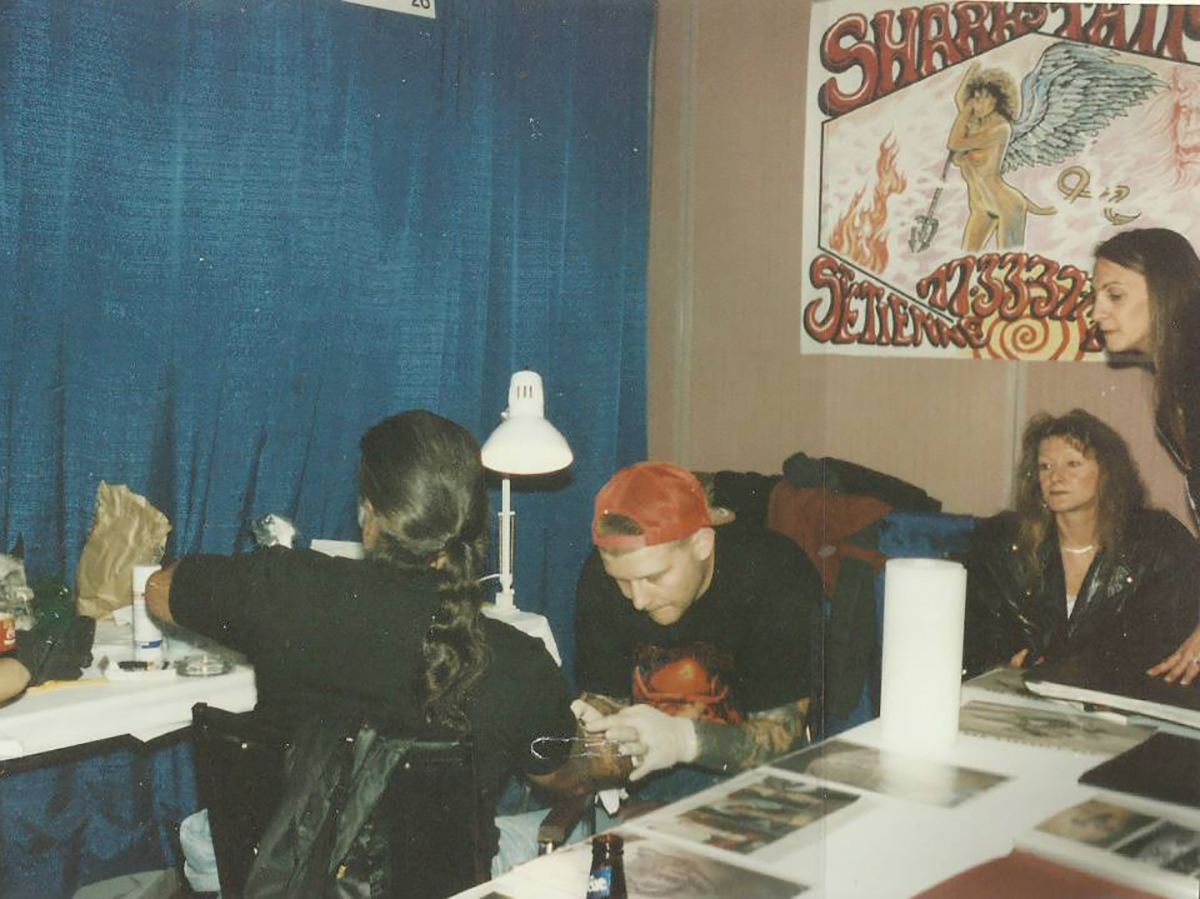

With 40 years in the business, French tattoo artist Phil Sharks from Saint-Étienne is one of the few professionals in France to have been in the craft for so long. Now 57 years old, he looks back for Inkers on his early days and at the same time retraces the beginnings of tattooing in France in the 1980s. Phil recalls the details of his passion, which, after having brought him out of a dead-end youth, finally made him the historical tattooist of his adopted city. He likes to praise the simplicity and the good life of “Sainté”, the only French city to have its own tattoo museum thanks to him.

How long have you been tattooing Phil?

If I count from when I got my first real machines, Spaulding (American tattoo equipment manufacturer and retailer), so when I started tattooing seriously, I'd say 1986.

Did you play with the needle before?

Yes, I used to tattoo my friends by hand. My mother was a seamstress so it was handy to get the needles. As I said, the Spaulding were my first real machines but before that I had another one, in 1980-82. This one was unusual, it was a vet's machine, a one-piece rotary that was used to tattoo animals' ears. The transformer was that of an electric train, the pedal a wall switch. So it can't really be considered as tattooing, but we had a good time with our friends and it was, in the end, nice.

Did you have any opportunities to observe machine tattooing?

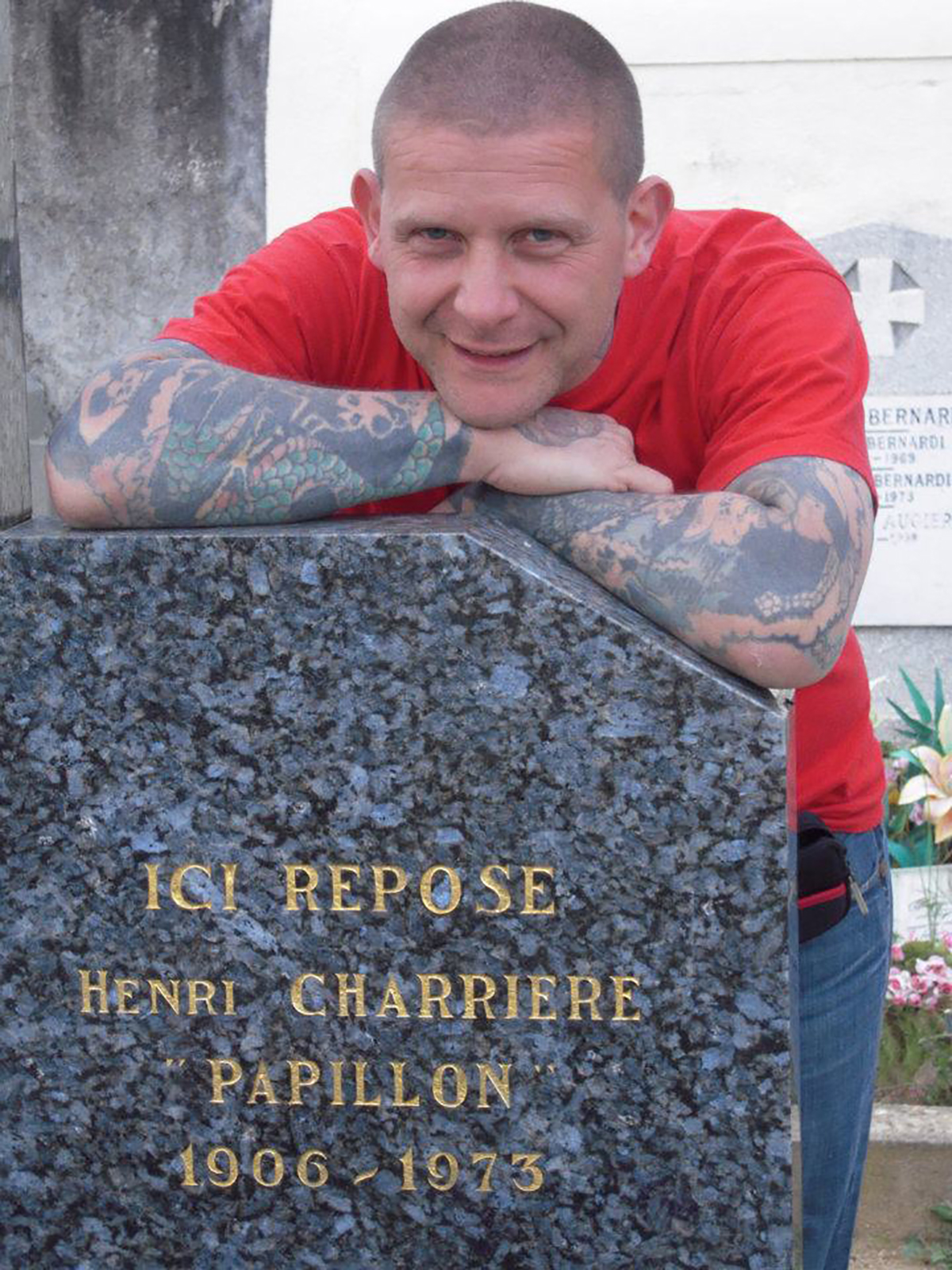

I had friends in Paris whom I used to visit - before I lived there in the mid-1980s - and I went several times to Bruno's, to Marcel's and also to Yvon's at the Puces de Clignancourt. When I went with them I saw what they were doing and I must say that it attracted me. But my first real influences were in music, in the record covers of the bands we listened to, Rose Tattoo or the Stray Cats. Like Bon Scott, the lead singer of AC/DC, they showed off their tattoos. I listened to punk, but also in the late 1970s southern rock like Molly Hatchett. The cover of one of their records introduced us to the American illustrator Frank Frazetta.

Do you end up getting tattoos?

Yes, by some older guys who also taught me how to tattoo by hand. They tattooed really well and soon my mates and I started doing things that inspired us. I kept my first tattoo, done in 1978, the Stranglers' rat from the cover of their first album "Ratus Norvegicus". We didn't really think about the machine, but it's finally one of these guys who gave me that first vet machine I mentioned. I exchanged it for a guitar amp - the guy was a very good guitarist -, under... rather special conditions.

What does that mean?

Today I can say that there is a statute of limitations. This amp, an Ampeg, actually belonged to a guy I didn't like. I knew where he lived and one day, in 1981, I went into his house, through the cellar door which was open.... The amp was 80 watts, it had two speakers, so when loaded on the back of my moped - I had a little Motobécane 51 - it was super heavy!

You were willing to do anything to get your machine?

Yes, I was. That night I was sabotaging my skin trying all this stuff out. I didn't know how it worked, it spat all over the place, the needles I was using weren't suitable and it all ended up looking like an ink stain in which I was tattooing as best I could while suffering in agony.

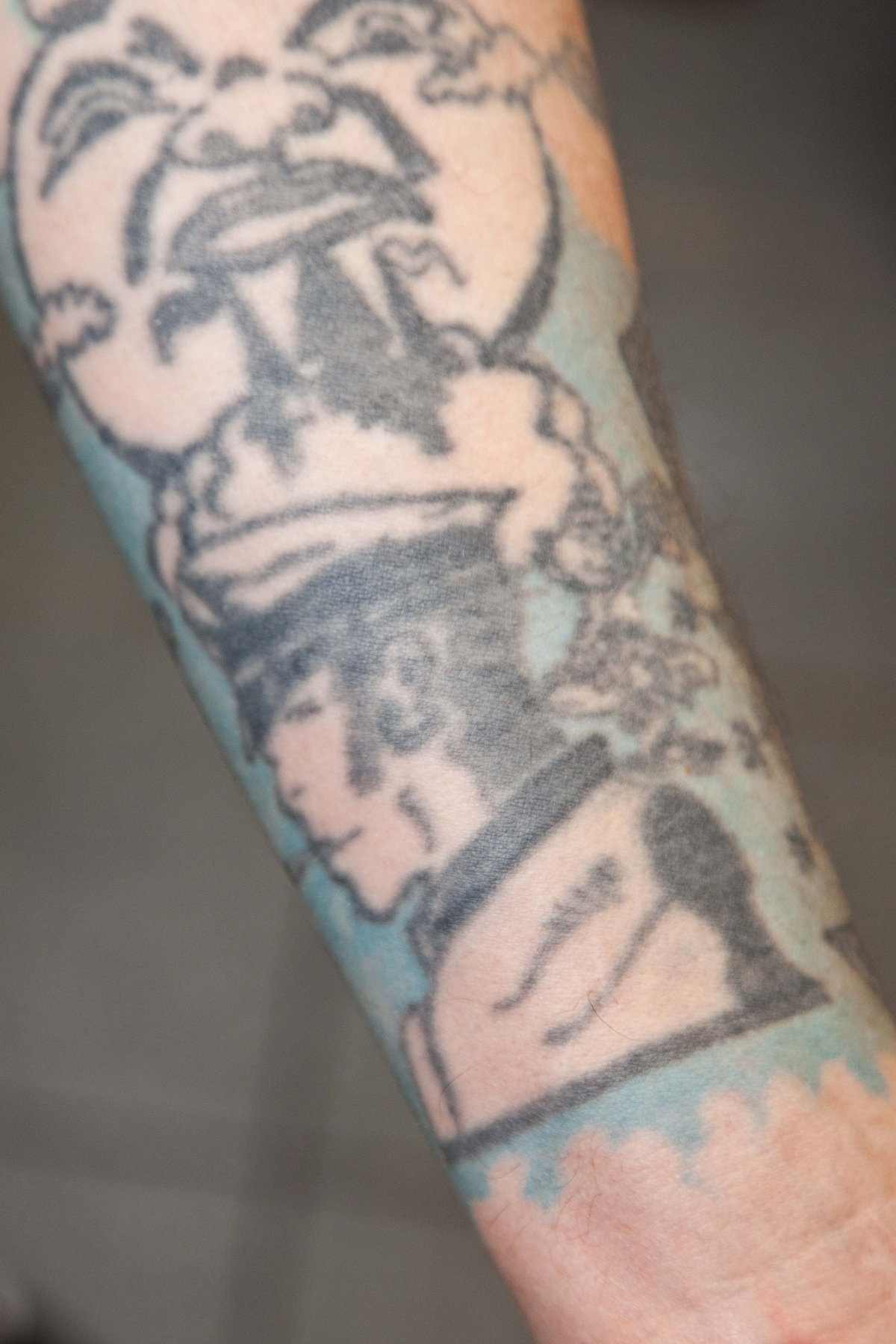

Have you kept those tattoos from back then?

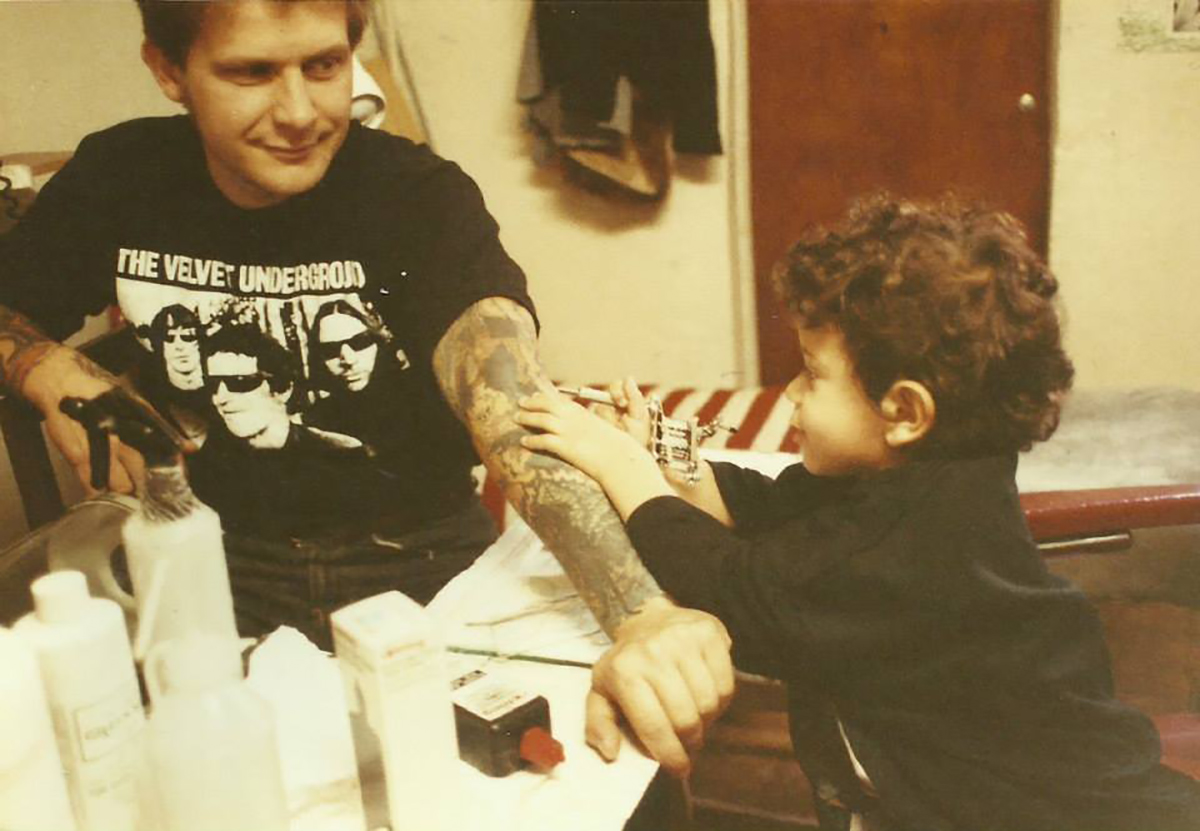

Look (he shows his arm), this Corto Maltese I did myself with this vet machine. The red one was gouache, it only went away a few years ago. See the turquoise? It's from the 1980s, it's a Spaulding colour, it kills.

What happens after this machine?

We started out as friends, then in the mid-1980s things got more serious with the arrival of biker magazines in France, like Easyrider. Inside there were advertisements, including Spaulding's tattoo material. As many did at the time, I also asked for their catalogue and by the time I received it, I had the time to decide that I was into it. With the money in my pocket, I ordered my first material...

It wasn't going to be cheap?

I was lucky. I didn't have any money but I made friends with an older guy, a businessman, who asked me how much I needed. "5000 francs" (about 750€) I said - which was a lot. "Well, I'll lend it to you," he said. Once I received the material I was like a madman. I almost slept with it! Later I had the opportunity to thank him.

At that moment you think you can make a profession out of it?

I had always liked drawing and I liked tattooing. And then I discovered all these tattoo artists in Paris who worked with machines and I thought it was cool. My problem was to learn. Because once I received the famous Spaulding material, there were so many elements that I didn't know what to do with them. I was just... observing.

What was your situation at the time?

I wasn't doing anything. Nothing but bullshit. I didn't want to do anything. My mates and I were into music, we were getting high and we didn't like anything. We didn't give a shit. We didn't like the world we lived in and we didn't want to be like the world around us, like the adults of the time. The tattoo was like a revelation. I said to myself, "Here's something I'm interested in". My old man couldn't see it. He said: "It's not a profession".

Did you have dreams?

To be a rock star, to do lots of free drugs and to fuck lots of girls.

Being part of a biker group too?

It was a world that attracted me a lot. I liked the hostile side: you come in and terrorise everyone a bit. But being part of a clan and a gang didn't appeal to me. I'm too independent, I don't like authority. Tattooing was not a smooth ride though. It was not a job. Whether it was to get the material or to enter tattoo shops, it was not easy. At Bruno's, for example (the first French professional tattooist, based in the Pigalle district of Paris, but also a distributor of equipment with the Jet France brand), the guys weren't very friendly. You had to put a five-franc coin in a turnstile to get in before being received by guys in grey coats. It wasn't the "cool" tattoo. At the other Parisian tattooists it was different, more mysterious, with an atmosphere. There was Marcel but also Christian from Belleville. He was in a more zen spirit, more rock'n'roll, more simple. There was a soul in those guys that you couldn't find in Bruno.

How did you get started as a professional?

I had a friend, from Roanne (city in central France) like me, who was doing tattoos in Clermont-Ferrand and he explained a few things to me. In Lyon, I used to go to Franck and Joce. I was watching. I didn't have the money to get a tattoo but I went with my friends and if you got on well with them they were not stingy with information. So I started to sabotage myself and my mates. I was progressing quite quickly in some areas. On others it was more complicated, but I was into it.

After the boredom, you finally had a goal?

Yes, I didn't want to be a jerk anymore. But I didn't think I'd make it my job. Because you have to realise that at the time there was one tattooist in every big city and that was it. So the prospects were slim. But I wanted to do it well. Anyway, in 1986 I was 21 and I was in Roanne. At home I set up a room for tattooing but I was finally obliged to free it up with the arrival of my son, so I took a small shop. It's hard work. I had made a lot of mistakes and in a small town it is difficult to get rid of the image that others have of you. People even had the impression that I was sinking a little deeper.

Did you stay in Roanne?

After a year I wanted to leave. I then took stock and realised that 80% of my clientele came from Saint-Etienne and the surrounding area. From Roanne it was easy to go to Lyon, which was the same distance away and where there was more going on, but I couldn't see myself living there. In Saint-Etienne, there was a working-class atmosphere which I liked.

No tattooist in Saint-Etienne?

One guy had been there for three months, otherwise no one. Once here, I realised it was cooler than I had imagined. Finding a place was not easy, but the solution came through a lonely, gruff old military man, not even tattooed, who probably liked me. I told him straight out what I wanted to do and he agreed, even accompanying me to the estate agency. I was in a discreet area, not too visible but accessible, in the centre. I often say: in cities like this, you have to be located like a sex shop, accessible but not too visible. My shop was old-school, you couldn't see inside, it was quite dark and there was always this mysterious side that attracted all sorts of fantasies: arms dealing, drug dealing...

How did the first few months go?

It started right away.

What was your clientele like?

A certain area came in at the beginning but it was good because I was rather hardcore. I liked this bad boy, slightly destructive side. I needed to let off a bit of steam - more verbally than physically, I should add. I made it clear that it was OK to have a laugh here, but that I shouldn't be taken for a fool. And I knew a few people through music, so I had clients from the punk and rock'n'roll scene. There was a lot of movement in Saint-Etienne in that respect. Then I very quickly had people from all walks of life, they could come in discreetly. That shaped me. I learned to express myself more correctly, to behave differently.

Do you get some publicity?

Yes, through the local newspaper, and I took the opportunity to improve the image of tattooing by insisting on hygiene, on the fact that the time of tattoo artists without gloves who sterilised with a lighter was over. I insisted on changing the dirty and dangerous connotation that still clung to the tattoo.

At what point do you say to yourself: "I've done it"?

When I had a sufficiently full appointment book, with a satisfactory waiting list. In the early 1990s, you had to wait three to six months, which was enormous. I had clients from all over the world, from Switzerland, from Italy. That was a recognition. So we received them well. Recognition is not what people tell you, but the way people do things. I finally had a regular income, an apartment and a landlord who, for once, didn't give me the cold shoulder.

Do you follow a bit what's going on in the industry?

Yes, thanks to the advertisements in the bike magazines. In Paris, in 1988-89, I used to buy foreign publications at the Brentanos bookshop, in the Opéra district, where I found Tattoo Outlaw Bikers and Tattoo Revue. There was also Hot Bike. We used to buy these bike mags so we knew who was doing what in France and what was going on. In Paris, I also found information at the "Parallèles" bookshop. And then Tattoo Time came along. I discovered the American tattoo artists Greg Irons, Ed Hardy and the Dutchman Henk Schiffmacher, people I later met at conventions.

Are you travelling?

Yes, I needed to meet other people, to discover other techniques, other tools. I wanted to surpass myself all the time. Conventions were starting to develop. I used to go to England, to Dennis Cockel's in Soho, Jock's in King's Cross... His place was rootsy, but it was the tattoo as you could imagine it at the time, with worn carpet and yellowed flashes. The first real convention was perhaps Dunstable in England, organised by Lal Hardy. I met Ron Ackers there in 1990-91, in the equipment stand run by Micky Sharpz, Micky Bee. I was hooked. Then more conventions came along and I tried to do them all. It helped me a lot, I turned a corner.

In France, how is it going?

It was more closed. There were guys like Tin-Tin who I had heard about in Toulouse, people from Lyon too with the old skins, it was cool. I met a lot of people. In the 1980s, I'd say there were about fifty tattoo artists, at most. And then it grows. In the 1990s, I'd say the number tripled. As far as conventions are concerned, the one in Bourges made a big impression on me, then the one in Paris in 1991 at the Elysée Montmartre - I even took part in the second one, where I met some great people, including Crazy Ace from Toronto. In the Rhône-Alpes region, I was the first to organise a convention in 1993-1994, at the Château de la Ferrière in Andrézieux. There were Neusky, Gros-Gros from Vichy, Jammy from Arles, about thirty tattoo artists in total. Then a second one in Saint-Etienne, with music groups that I liked. It made tattooing live here, where I was still the only tattooist.

No tattoo without music and no music without tattoo?

First of all, it's music. It is through music that I came to tattooing.

When you start, do you draw according to the flashes sent by Spaulding with his material?

I used to draw all the time. Spaulding's flashes were very small, so we had to go to the copy shop to enlarge them before we could personalise them. I liked copying to learn. But what I didn't like to do was the very thing that popularised tattooing in the 1990s: tribal. I preferred Japanese. I discovered Horiyoshi III very early on and I was amazed. Horikin's work too, he was fully tattooed and had also tattooed his wife. It was something in the 1980s.

Who were your references among the illustrators of the time?

I got really hooked on Franck Frazetta when I saw that I could tattoo his drawings, like the cover of the band Molly Hatchett. Later there was Boris Valejo... In Lyon, Franck Tattoo loved it, he did a lot of freehand adaptations of Frazetta. The explosion of role-playing games in the 1990s also opened the way for new illustrators, some of whom were very talented, like the American Gerald Brom. They brought in other ideas, a certain freshness. And then people started to mix record covers with traditional tattoos. They were more aware of what was possible. I had quite a few hard rockers - before they were called metalheads. I don't necessarily like that music but bands like Iron Maiden or Megadeth had crazy covers that fans would ask me to do. I was having a blast doing these big pieces.

In the end you stayed in Saint-Etienne?

Yes, but not only because it was working well. I simply learned to like this city, with its proletarian, simple, friendly side. You go to a bar, people talk to you easily. It's a pleasant city.

You finally became the historical tattooist and as you said, at that time it was one tattooist per city. How did it go with the competition?

I started getting them in the early 2000s. I knew there would be an evolution but I didn't know it would become so important. Six to seven years ago tattoo artists were popping up everywhere. When new shops open, they don't usually come to me. But I show up in every one of them. I see how they are, what their reaction is, if they are nice. Sometimes it's hypocritical and sometimes they come, I like it.

How do you see the evolution of tattooing in your city today?

It's a bit like everywhere else, there's something for everyone. I can't even criticize those who do it at home any more, because some are more talented than others who are well established. Tattooing is for everyone. I would even say that - it's maybe mean - it's become a traditional profession, not so much rock'n'roll. It has lost its soul. I have rare collectors' items and I invite everyone to come and see them but, in the end, very few people bother to push open the door. You can't talk history with them, some of them don't even know how to assemble or disassemble a coil machine. But you tell me, there's no need now.

What do you miss most about those years?

The guys had an artistic soul - even if I don't like this word - they had an artistic culture and were inspired by painters and illustrators. And you had to really like tattooing because it wasn't a profession open to everyone. You had to be prepared to be rejected, especially in small towns like this. A lot of people wouldn't have started at the time when I started. Nowadays, some people do it because they think they can make money easily, because they want to be considered as artists. I insist on the fact that I am a craftsman. What I mean is that many people show off without knowing the origins of the profession. But we live in a superficial world and I like people who are discreet, efficient, who do what they have to do.

Do you regret the time when, as good craftsmen, tattoo artists had more control over their equipment and made their own colours, for example?

I don't regret it because it was still restrictive and nowadays there are high-performance colours. But it also had its charm and was part of the job. We didn't complain as much as we do now. We were happy to get our pigments and to do our own colours - which you do in fact once in large quantities and for a long time -. But the thing that tattoo artists today know little or nothing about is soldering. You had to prepare a whole week's worth of needles - well, I worked on a weekly basis. I would weld them, then ultra-sound them, then dry them, then wrap them up and sterilise them.

Do you work today with a restricted colour palette?

Yes, I stay with very primary things. This allows me at least to be sure of their availability when some appear one day and disappear another. At least the basic colours are always there.

We see a lot of realism in your work at the moment.

Actually, I'm doing quite well. I've gone back to more basic, old-school, realistic things that last.

Can you introduce us to the studio and the people you work with today?

John -Jojo- has been with me for eight years. He's very passionate about everything geometric and unstructured, which he interprets with his own style. He's a jack of all trades who did his apprenticeship at the same time as Jess - Martucci, now in London. I've had several other people in the meantime and then Gaëtan arrived two years ago, who is more into neo-trad. Finally, Mélanie has been there as an apprentice for a year and a half. It's a good team.

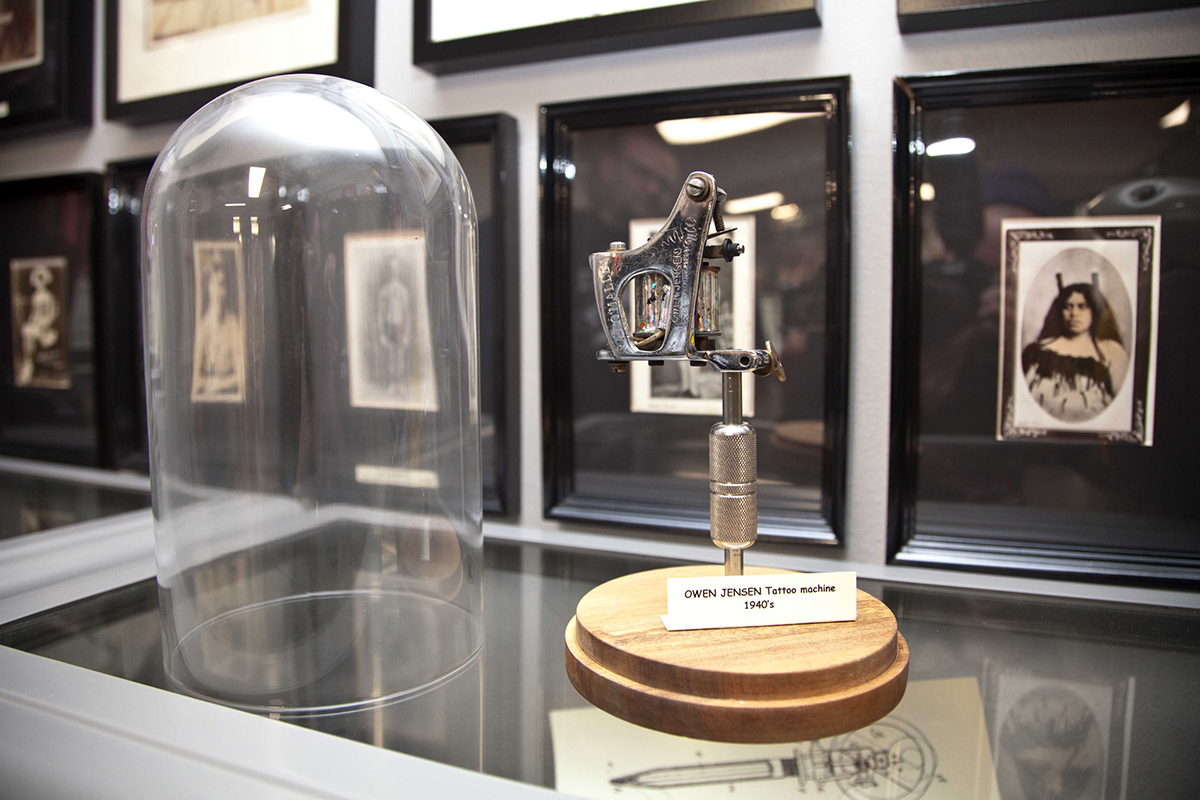

This studio, in which you have been living for three years, is also a tattoo museum. You exhibit a part of your collection of objects linked to its history. Can you tell us about it?

I wanted to share it with other people. And making a museum about tattooing in a studio was part of the trick, many tattooers have done it before me. It's a way to give a bit of soul to my shop and to exchange with the curious people who come.

Where does this collection start?

From the very beginning of tattooing I had to be interested in the history of tattooing because the tattoo artists who brought the tattoo were part of it: Bob Roberts, Lyle Tuttle, Jack Rudy, Brian Everett, Ed Hardy, etc., it's the History of the American tattoo. Then there are the older ones and before I drank Sailor Jerry rum I already knew who he was. In the 1990s and 2000s, I was really into it and for 15-20 years I distanced myself from the historical aspect. I got back into it when I realised the value of the stuff I had, like my first Spaulding machine, the books I had collected, some hakata dolls (Japanese ceramic painted dolls)... New historical publications also came out and enlightened me about what had happened. This got me back into it and I said to myself why not make a small collection. I quickly became passionate about it. I discovered things, it was still possible to make good deals at the time.

What are your favourite parts?

My Owen Jensen bike; a 1930's Detroit kit whose origin I can't clearly identify; I also have a Chicago kit with a wood-mounted transformer, pedal and machines and a portable battery-powered rotary kit - it's basically the first battery-powered rotary machine sold by the Moskowitz brothers of New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s. There's also my little drawing of Sailor Jerry, with the acetate and the business card; it's symbolic but it's nice. Finally, I have a 1944 photo signed by Charlie Wagner (early 20th century New York tattoo artist) himself. It's from a series I used to see everywhere, but now I have an original. It's a pleasure. And then I have original albumen photographs of Japanese tattooists, it's so beautiful!

Is there a piece missing from your collection?

The one I would like to acquire, like many, is Edison's original tattoo machine (from which the first electric tattoo machine was patented in 1891 by Samuel O'Reilly). For the moment, I only have a copy, made by young Russians. + IG : @philsharks Sharsk’s Tattoo 33 Rue de la Résistance, 42000 Saint-Étienne www.sharkstattoo.com