Driven by a deep desire for artistic creation, the young French tattoo artist Harry Kazan recently moved to Japan. There he explored the vast traditional culture of the archipelago, which he reinterpreted through various projects, including a photographic series mixing the fantastic world of the yokai with a Tokyo 3.0 aesthetic.

You've been living in Japan for some time now, what made you decide to move abroad?

I arrived in Japan about two years ago, driven by a feeling of need for artistic creation but also by a feeling of being fed up with the atmosphere in France. It's complicated to explain, but I know that many people who, like me, have left their homeland will understand this feeling.

What is it like for a foreign tattooist in a country that has a very complicated relationship with tattooing?

I've been here for two years, so it's still a bit too fresh to really talk about a "normal" daily life. And then I arrived at a time when the borders were closed, so most of the customers who really consume tattoos, the foreigners, can't come. Fortunately I still have my Japanese clientele, mainly young people aged 25-30 belonging to the hardcore metal scene. In short, it's an adventure every day, but I like it.

Artistically, what kind of tattoos do you propose?

I try to mix Japanese imagery inspired by yokai of all kinds, with references to the Noh theatre and a style close to black work, combining pure black and shades of dots.

This stay in Japan is the opportunity to get interested in the traditional tattoo culture, isn't it?

Yes, because it's a great opportunity to be in this country and to have access to this culture. But it's not something I want to copy line by line. There are codes, apparently simple, almost childish, but which are in reality extremely complex and I am passionate about trying to understand them, to adapt them to what I do.

You seem to be particularly interested in the world of yokai, don't you?

I love everything that revolves around demons, spirits and Japanese urban legends. I am lucky in Japan to have access to resources that are almost impossible to find in France. In my studio, I have entire encyclopaedias on Japanese legends. It's a paradise for me.

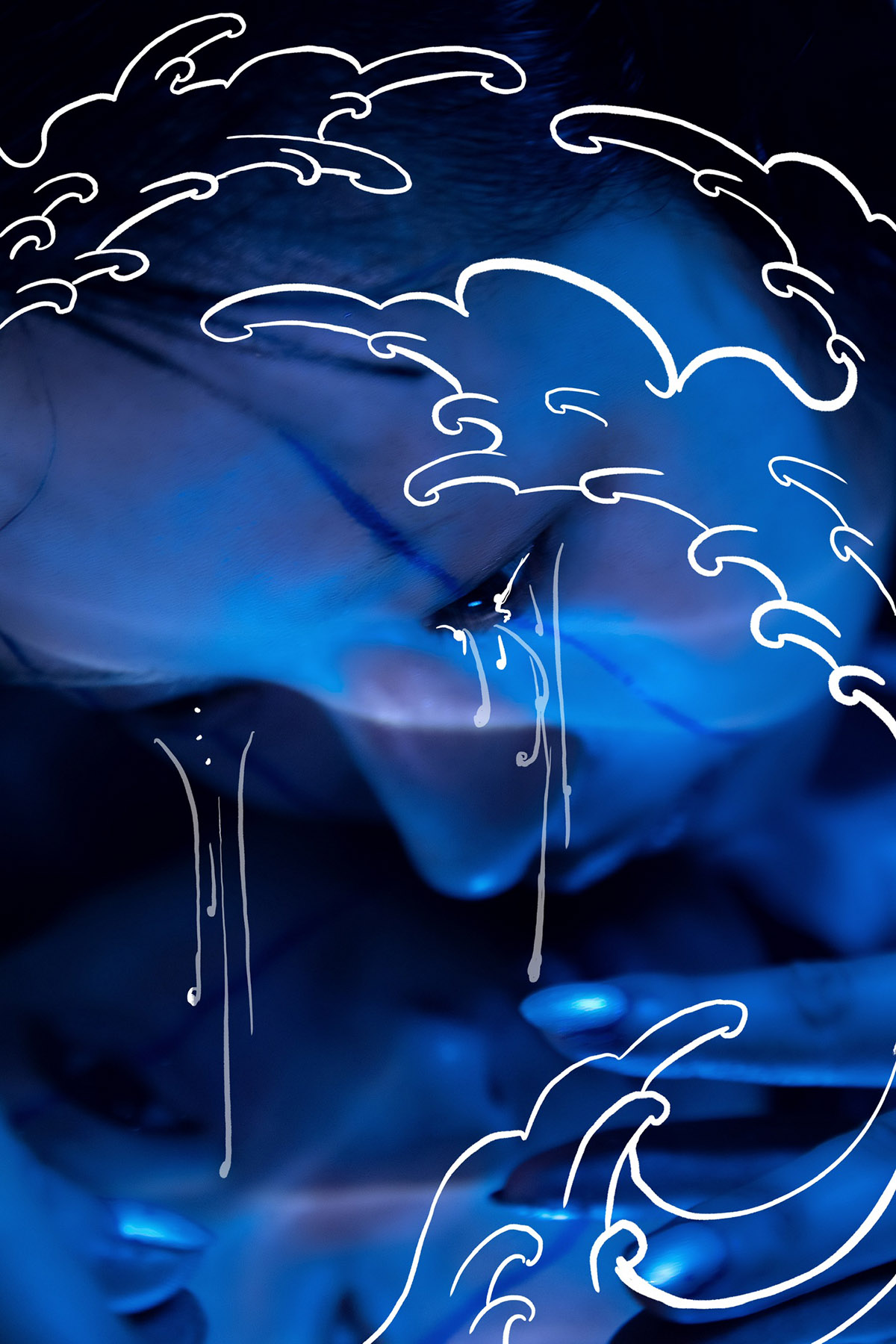

We find this interest in a series of photographs that is a bit different from your rather monochromatic instagram, how was it born?

This series was born from my meeting with Solène Ballesta, an incredible photographer. From the moment we met, we thought it would be cool to collaborate on a project, without really knowing which one, until I exhibited masks in a gallery -Atelier 485- in which the idea was to reinterpret Japanese culture through paintings, masks and mapping. The masks were the central element of this exhibition which was paralleled by three abstract paintings representing Zohonna's evolution towards Hannya (in Noh theatre, hannya is the final phase of the actor's transformation after two previous stages).

What were your desires for this series and how did you divide the roles?

We quickly agreed on the fact that we wanted a slightly mystical atmosphere but also a bit of cyberpunk, Neo Tokyo, etc. Solène was in charge of organising the shoot and it went really fast, in a snap, thanks to her. Solène was in charge of organising the shoot and it went really fast, in a snap of the fingers, thanks to her. Setting up a shoot is often a pain in the ass so we were pretty lucky. Solène then pre-selected about a hundred images before narrowing the selection down to about fifteen. The photos were then cropped and retouched, and I digitally modified them.

How did you go about it?

I used software such as Illustrator, Photoshop or Procreate to draw on the photo, then distort the lines, integrate them more or less subtly, cut out parts of the original photo and replicate it elsewhere in the frame, etc. Digital technology was used to show the gap between tradition and futurism. Digital technology was used to show the gap between tradition and futurism.

The hannya mask is often used, why this one in particular?

It was purely aesthetic, because in the collective unconscious of the West it conjures up a rather mystical image of Japan. This mask is very popular in everything related to pop culture, tattoos and art.

You mentioned masks, what interest do you have in them?

More than anywhere else, I think that in Japan the mask has an essential role in everything that concerns entertainment, religion and art. Whether it's in the matsuri (popular festivals) with the masks of Hyotokko (the grimacing face of a comic character wrapped in a white polka-dot scarf) and Okame (a round female face with full cheeks), in the temples with the dance of the Shishi (Chinese lions) for the new year or in the theatre with everything that revolves around Kabuki and Noh. It fascinates me.

The mask is a work of the craftsman and you told me that you create them yourself according to a very particular approach. Can you tell us about it?

My approach is unusual. I spend most of the year gathering physical or digital information on a lot of subjects in order to create a sort of data bank. Then, when the time comes to produce, I lock myself up - almost literally - in a workshop to make the most of these months of research. Then, trials and failures follow one another until I finally come up with a convincing result.

Do you use wood to make them?

No, I use resin mixtures to duplicate and modify the masks more quickly. My initial plan was to produce about 50 of them. Making them in wood would have been too expensive, both in terms of time and money. I had planned to make one in wood, 1.5m high, but I decided to postpone this project. + Instagram : @harry_kazan