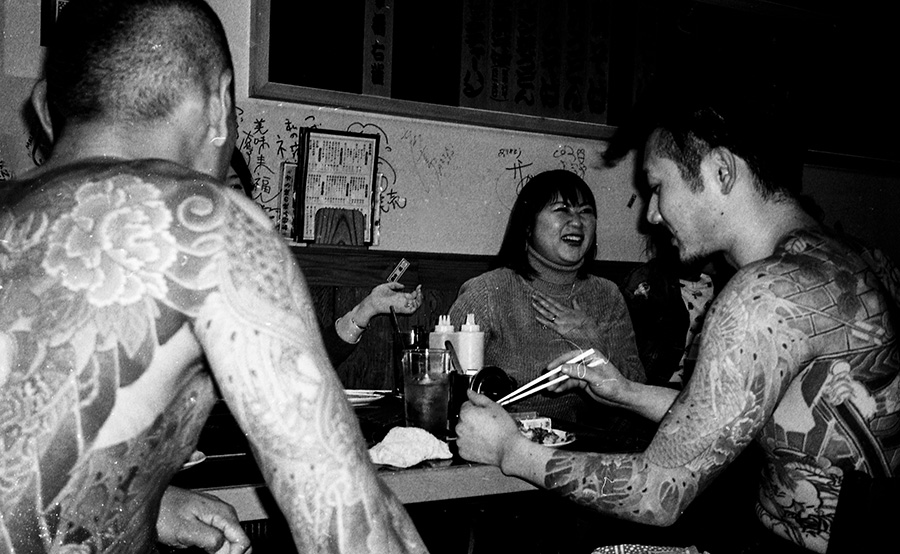

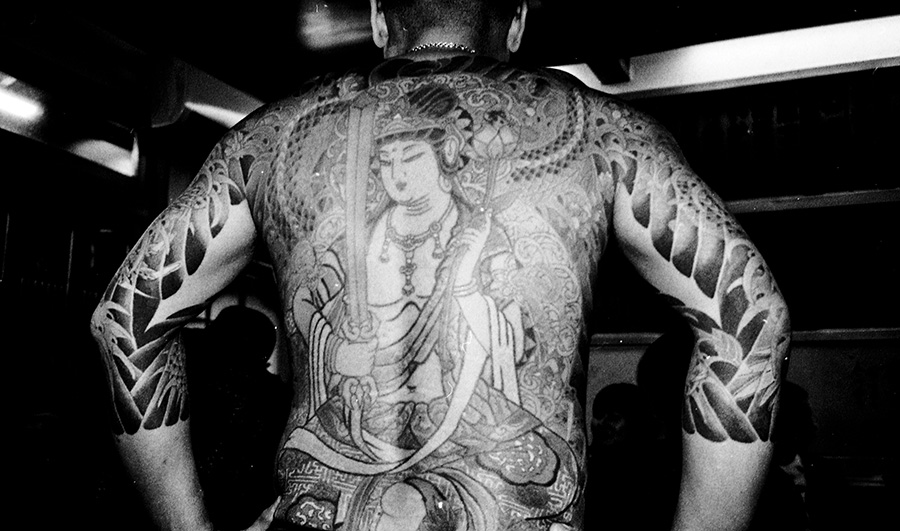

The Dutch photographer Ronin de Goede shares in his latest photobook “Asakusa” his unusual photographic experience into the world of Japanese tattooing in Tokyo, between the studio of a great master, the largest annual city street festival and a group of yakuza.

How does the story of this book begin? What period does it cover?

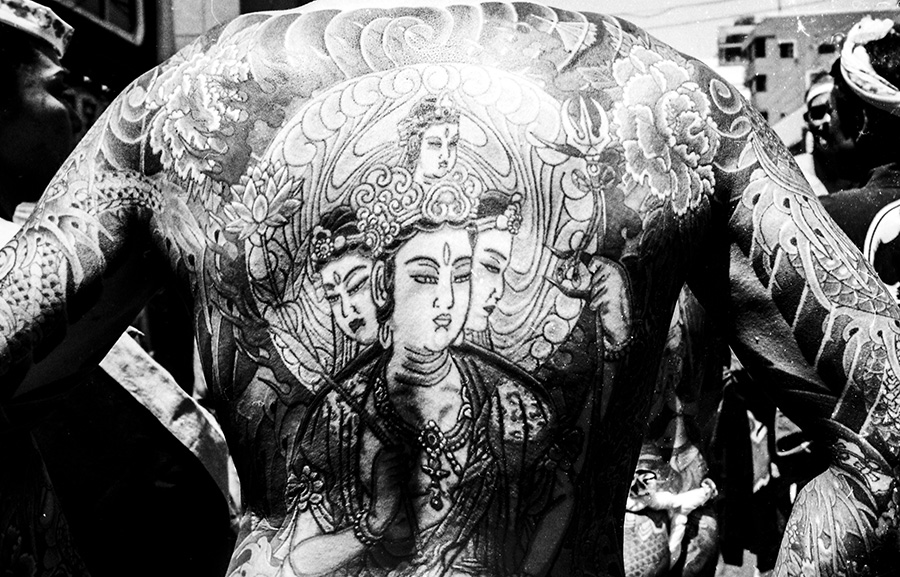

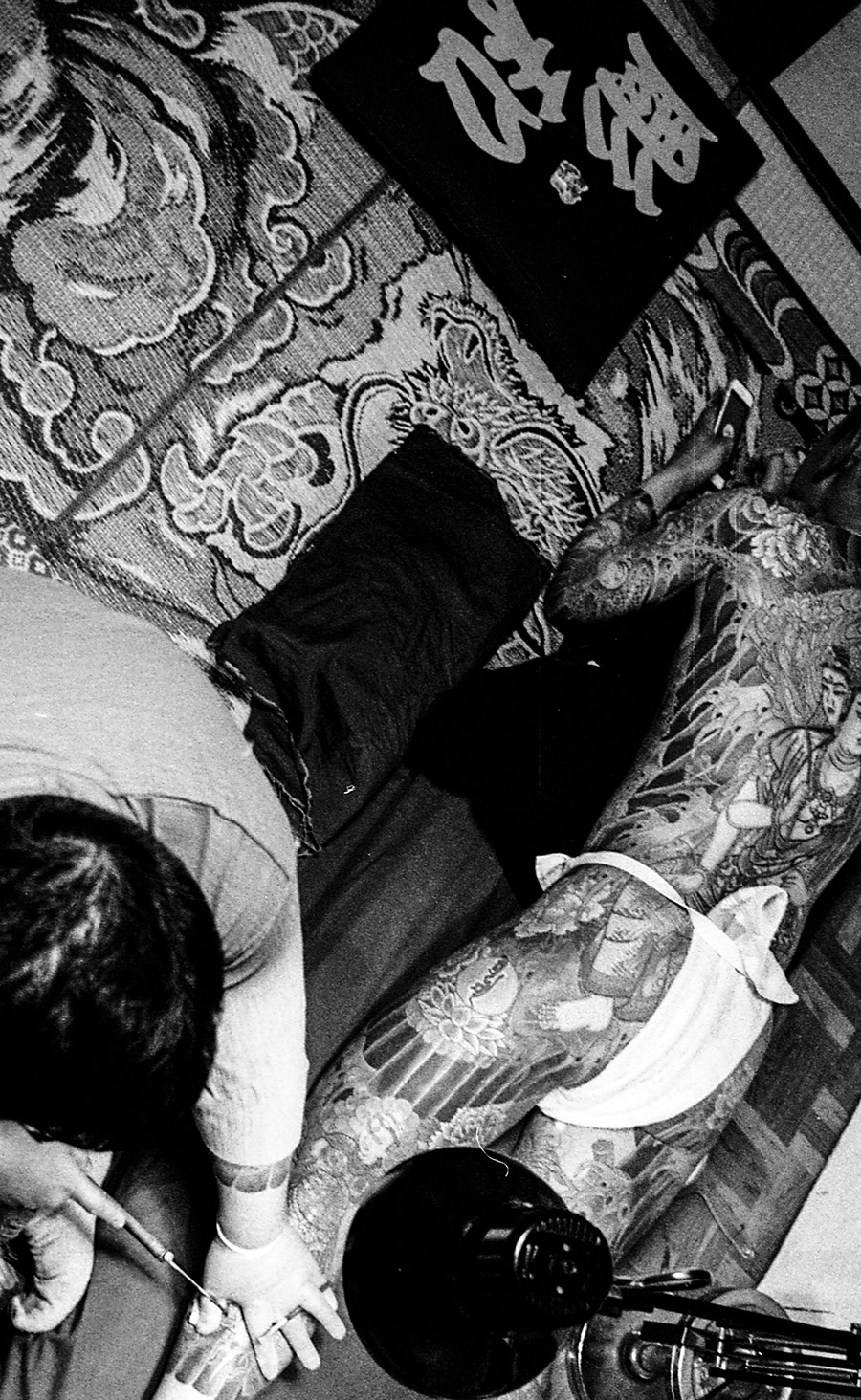

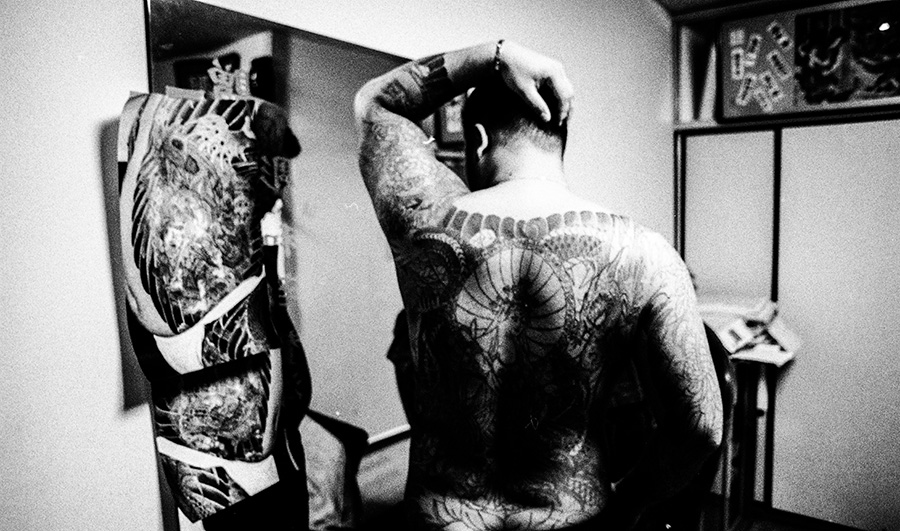

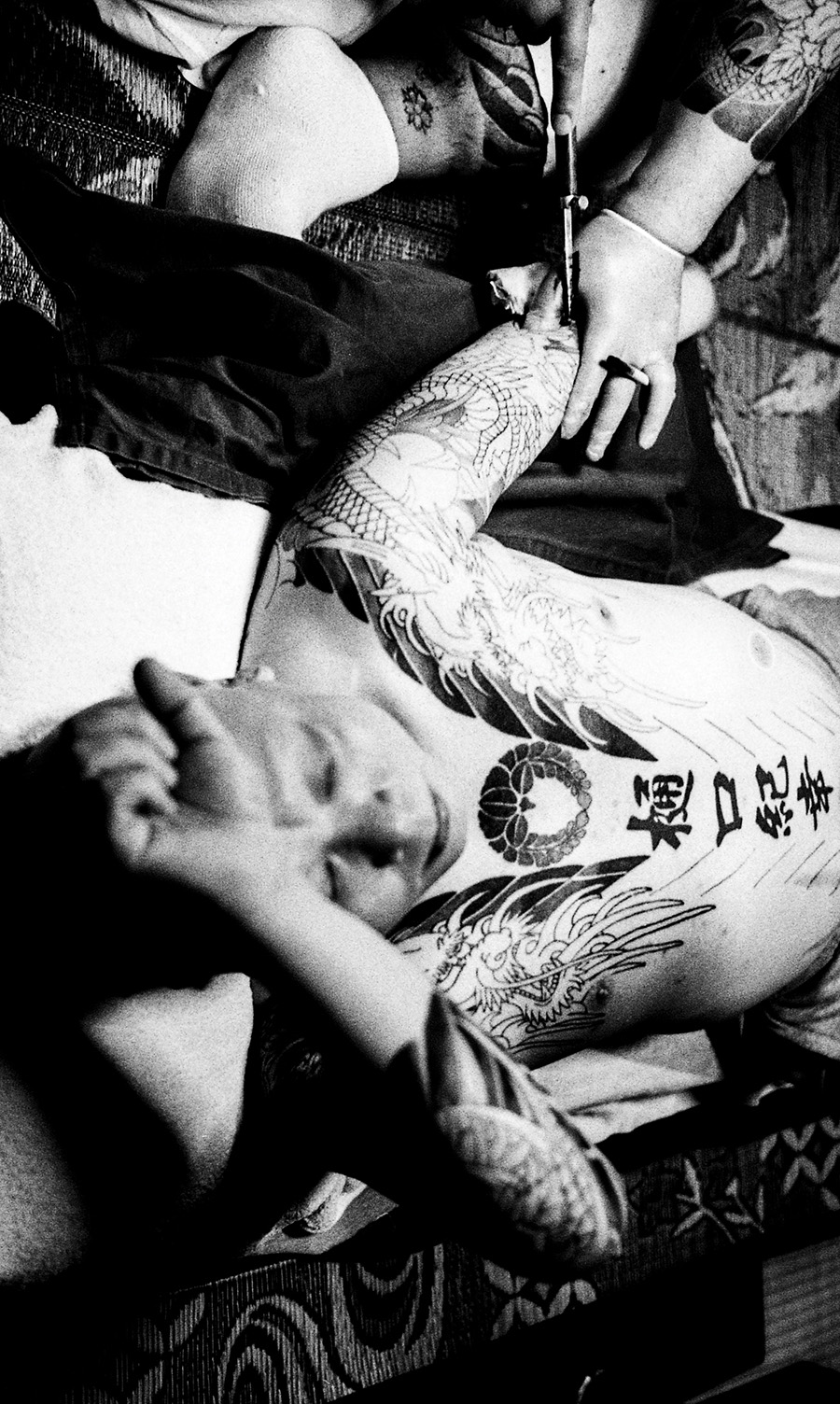

Before I was introduced to Horikazu Sensei, I had already been familiar with the world of traditional Japanese tattoo “wabori” through my friends: Horimyo, a young master from Saitama prefecture and, years later, Marco Bratt, a Dutch tattoo artist specialising in Japanese style. It was Marco who introduced me to Horikazu, who at the time went by the name of Horikazuwaka. Later, when I was invited to work on the 2nd revised edition of “A history of Japanese Body-Suit Tattooing” by Mark Poysden and Marco Bratt, I started visiting Japan more often and became actively engaged in photographing the master’s clientele. Primarily for this project I used (digital) editorial photography. Nevertheless, I always held on to small analogue cameras on the side, slowly creating a personal visual diary of my Japanese adventures. It is the selection of these fortuitous shots of the neighbourhood, the Sanja festival and encounters with people that became the basis for my book “Asakusa”.

How did you see tattoo culture in Japan before this adventure and how did it change after that?

Prior to my visit to Japan, I was not much into tattoo culture. Working in Japan and being introduced to many ‘horishi’ made me more curious about the culture, the skills and the respect for tradition.

Why did you choose the name of the Tokyo district Asakusa as the title for this book?

Traditional Japanese tattoo (both historically and up to the present day) is embedded in Shitamachi Tokyo, especially in the Asakusa district, where many ‘horishi’ reside. I fell in love with the neighbourhood, the public bath houses and the spirit of the old Edo, which still breathes against the backdrop of a constantly changing modern Tokyo.

Photographing was not as easy apparently, it looks like you had to prove yourself to the tattoo artist Horikazu in some way and do some little works. Can you tell us about it.

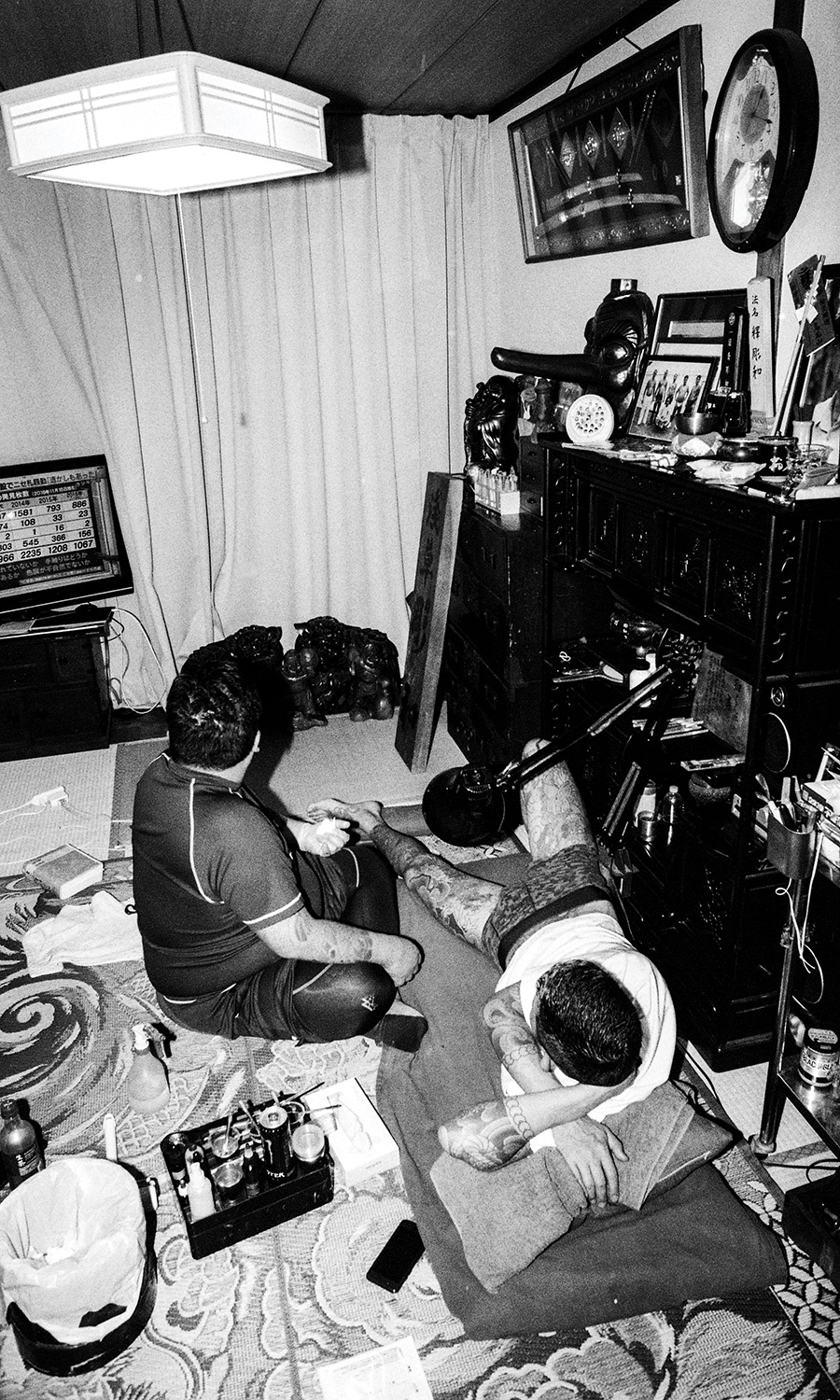

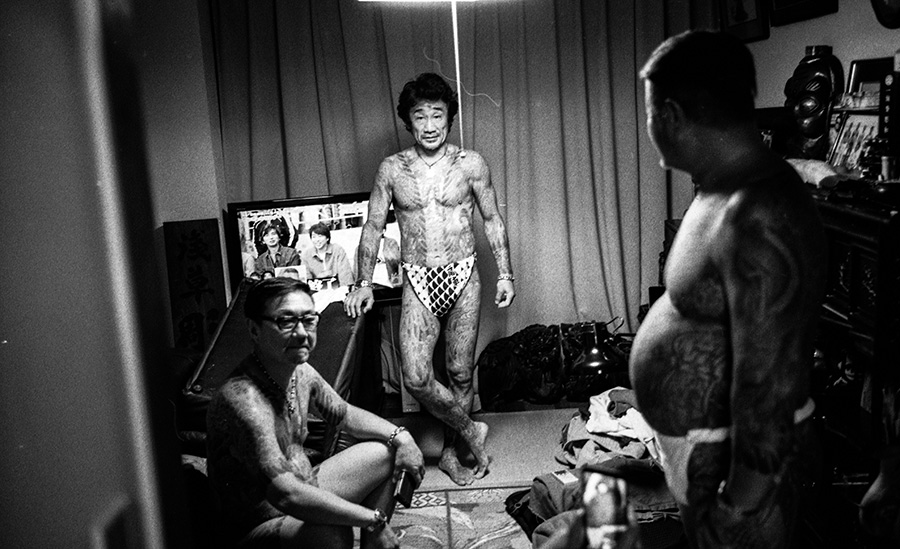

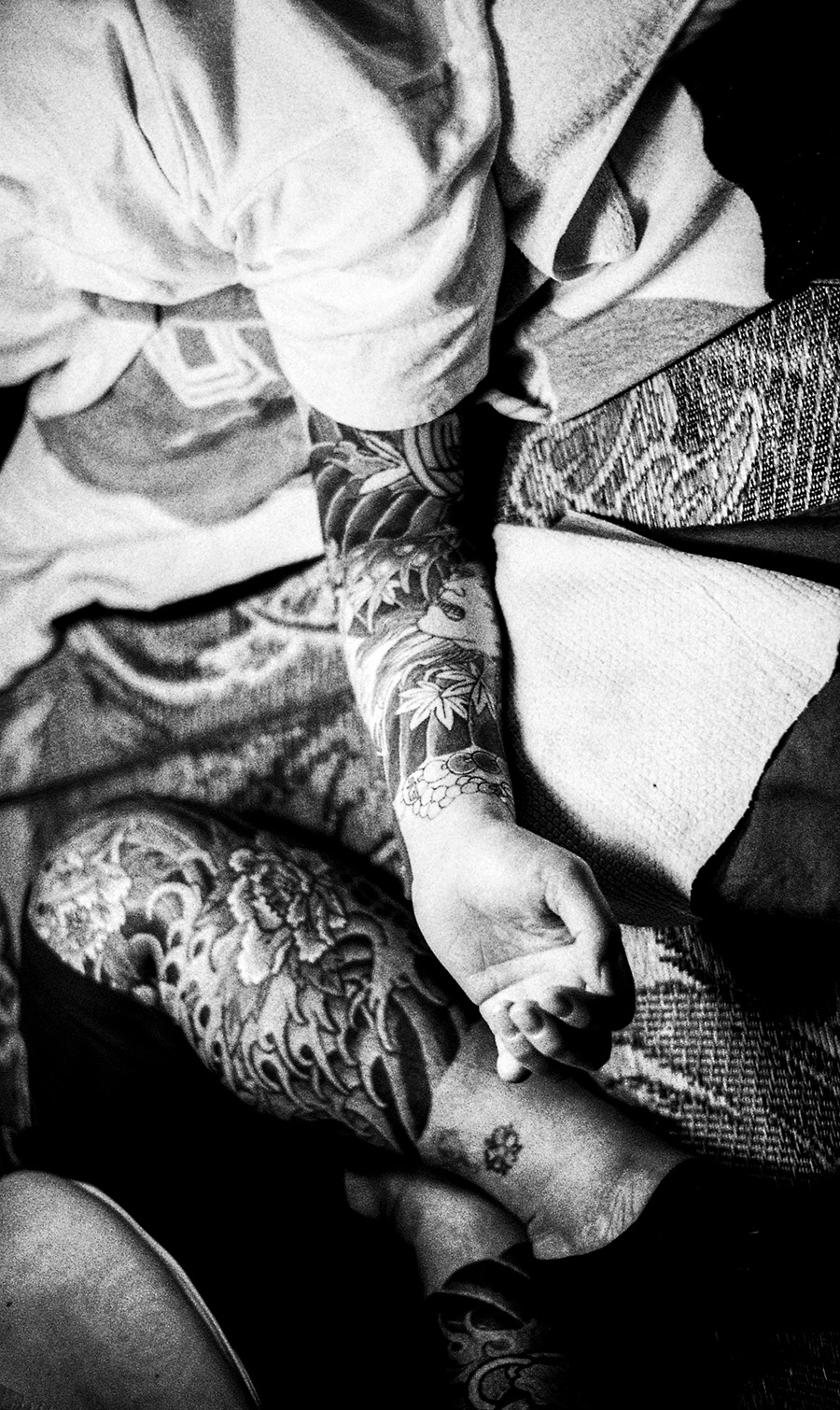

At the beginning it was not always easy. I watched hours of ‘tebori’ sessions before I could actively start taking pictures. I always stayed at the master’s mansion or studio that kept us closely together: working, eating, bathing and sleeping. After work I met with his friends and family and slowly my presence became natural, resulting in significant friendships.

Horikazu is a respected master, of Second generation – his father was also a tattooer named also Horikazu-, what were your relationships with him ?

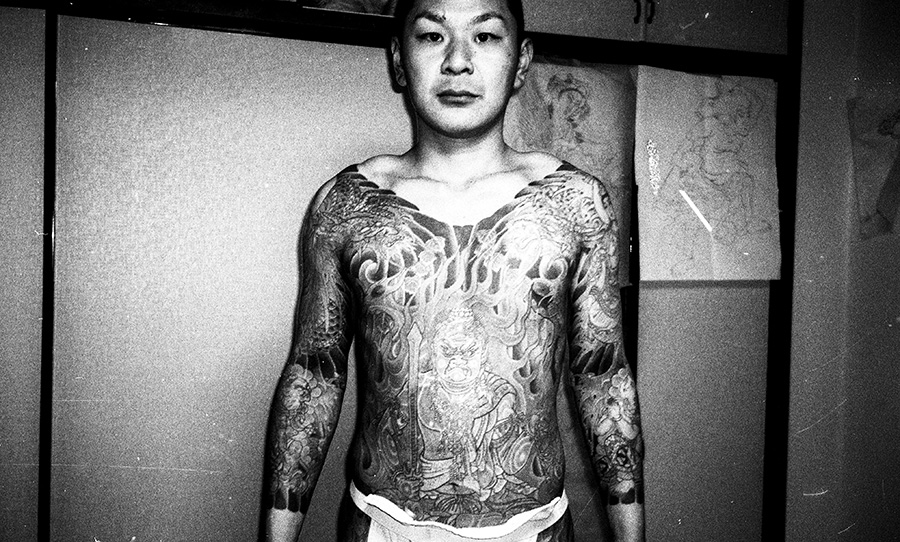

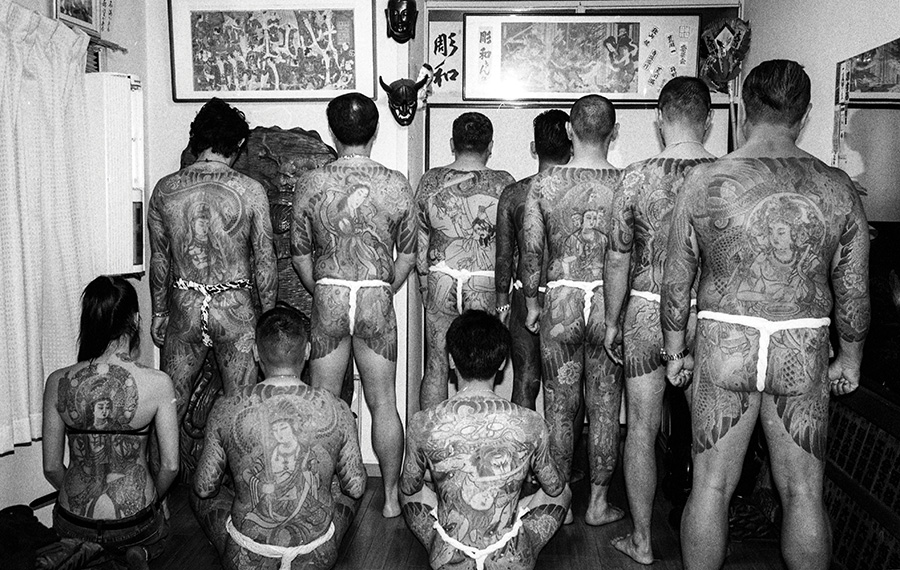

Unfortunately, I have never been able to meet Horikazu Shodai (the first) in person: his medical condition was too poor. In the meantime my friendship with his son has always been special. The work and style of both father and son are exceptional and unique in the world of traditional tattoo. It has always been an honour to follow master Horikazu, to see his work and methods from inside and to get to know him personally. (Note that not all tattoos in Ronin's images are works of Horikazu).

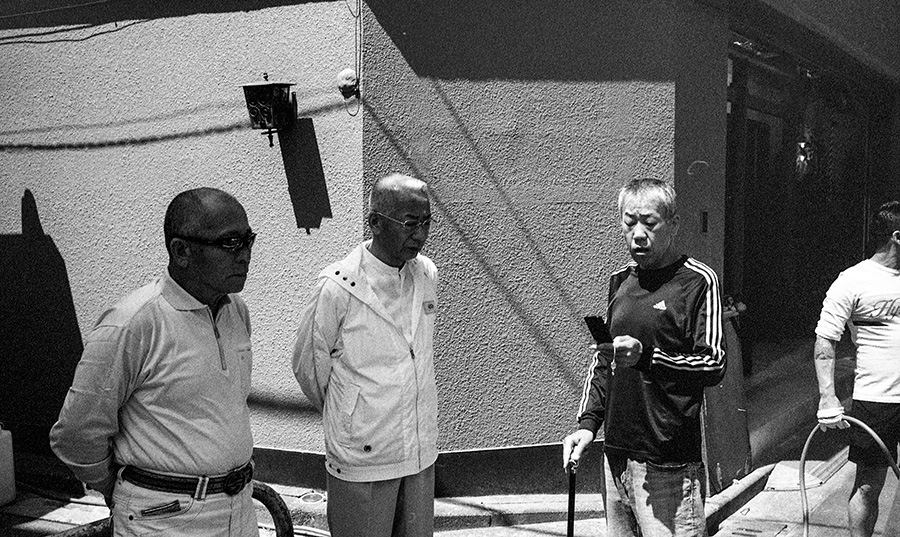

Your book replaces the culture of tattooing among the yakuza but the anti-gang laws in the 1990s had the effect of reducing their number and gradually making them abandon distinctive signs such as tattoos to blend in with society. Are the tattoos still popular with these men?

Not all the people in my book are yakuza or openly identify themselves as such. In my personal view, in the Shitamachi area “horimono” is still very popular among members, it might be less in other parts of Japan.

Do you have an idea about the proportion of Horikazu's customers being yakuza ?

Neither am I in a position to present any credible statistics with respect to master’s clients nor have I met all of them (and there are a lot!). What I do know is that all clients always treat the master with great respect. Some of the clients have a privilege of receiving their tebori sessions in the sanctuary of their own homes. Those were the visits I always enjoyed making photos of.

What is the relationship to tattooing for these men? Is it an obligation, a fashion, an intimate and sincere relationship?

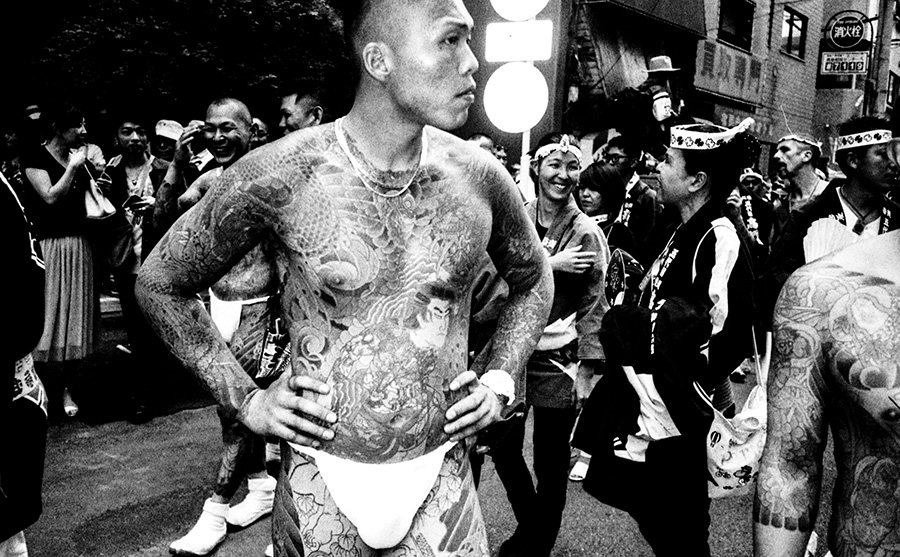

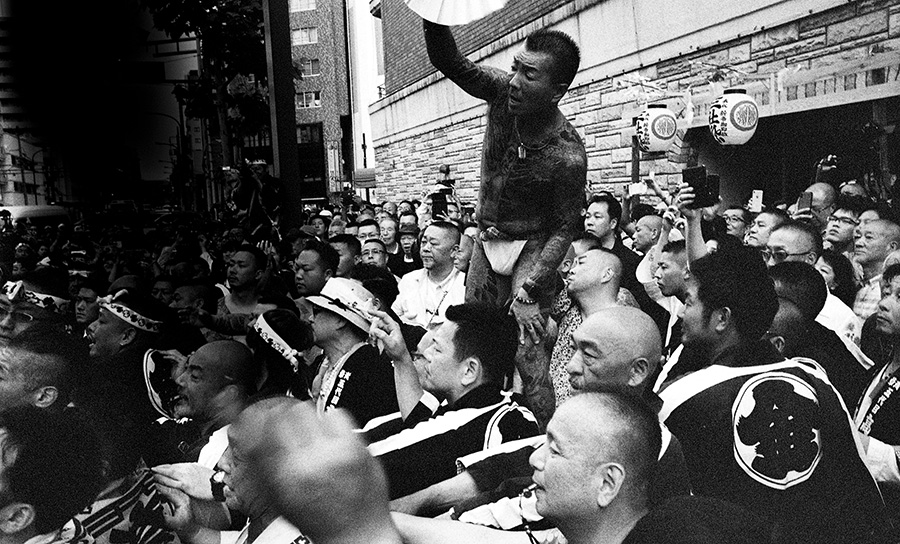

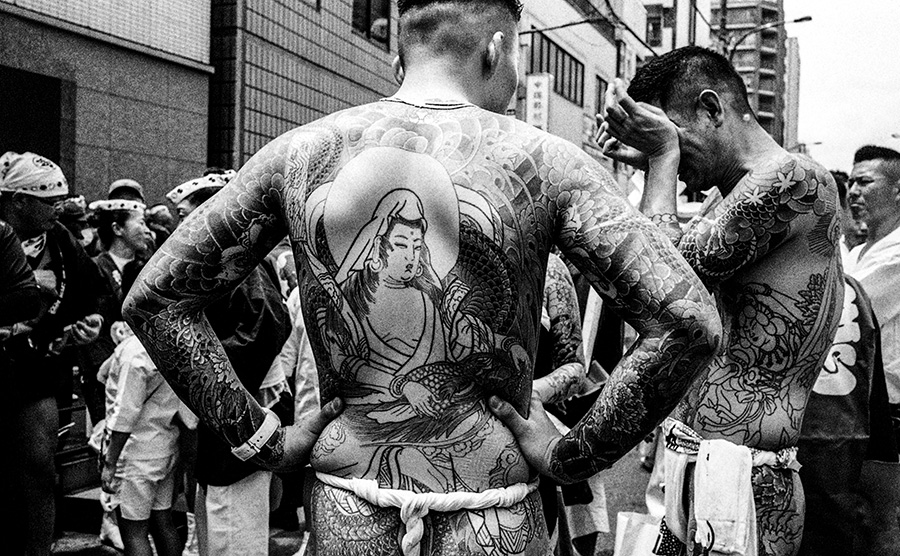

I suppose it depends on personal circumstances. For some people, perhaps, it is an obligation, others might consider it fashionable but, in my experience, most clients have a more intrinsic motivation. Some believe sincerely in the protective power of the motives and the “sumi” (the ink) that is used. Many clients participate in different Shinto festivals, where they use the opportunity to reveal their tattooed bodies, while carrying, riding or standing on a ‘mikoshi’. The Sanja Matsuri festival is the most famous example of this phenomenon. The time preceding the festival is a particularly busy period for the master: his clients want to finish, retouch or even cover some old tattoo works in time before the festival.

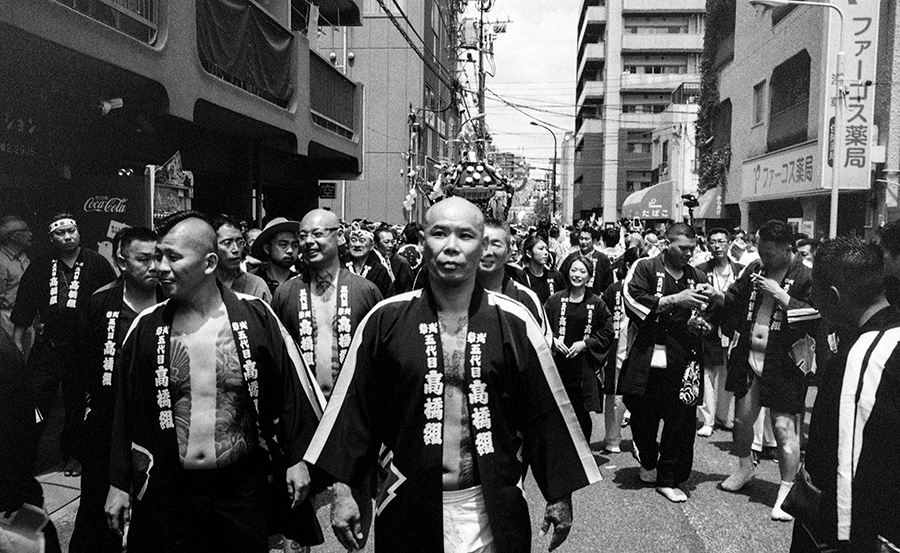

In the book Mark Poysden says you became the official photographer of the 5th Takahashi-gumi, a yakuza group. What interest did this honor serve according to you?

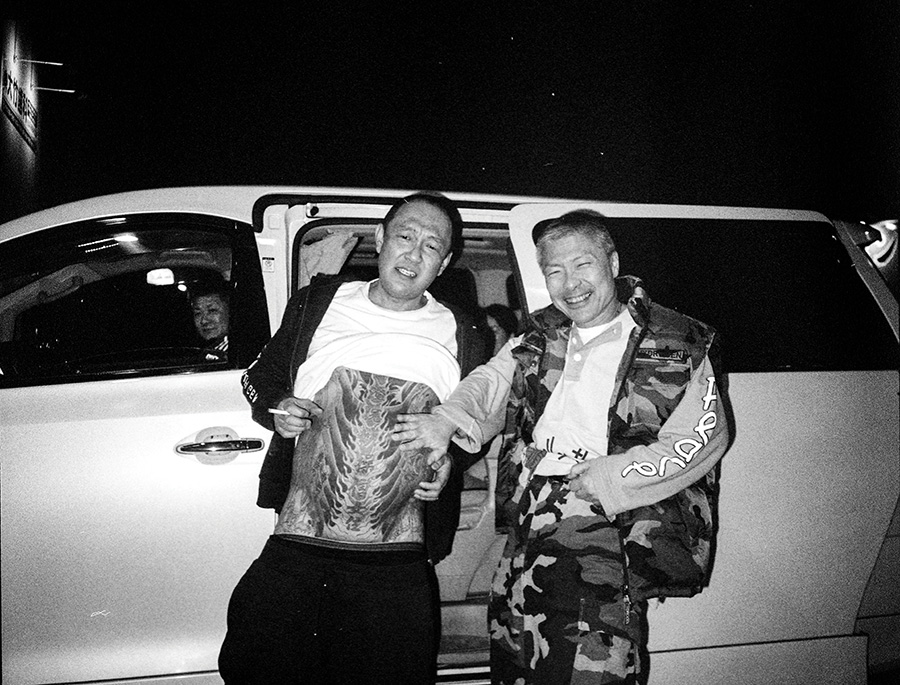

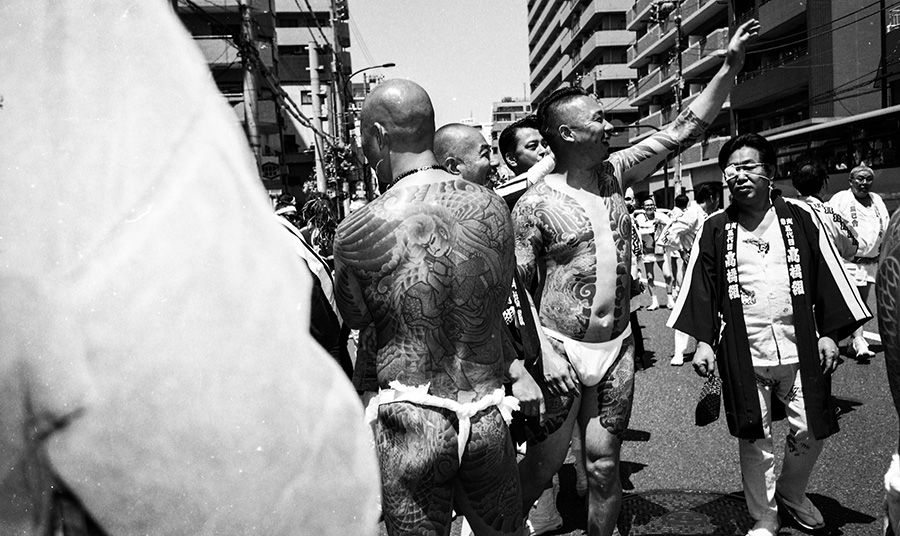

In the book my friend and author of the introductory text, Mark Poysden, refers to me as “an” (and not the) official photographer for the Takahashi Gumi 5th Generation during the Sanja Festival. As I had already been working during the Sanja, I was invited to focus on some specific photography, mainly the official group shots near the local office and with the Mikoshi, preferably with the Senso-Ji and Sky tree in the background as particular landmarks of the area. A selection of this more (digital) colorful work was then sent to the group to use for their annual Matsuri calendar. That was a nice way to give something back for all hospitality that I had received from the group before, during and after the Sanja festival. Unfortunately, Mark words are sometimes misunderstood. Just to be clear: I work in my personal capacity and have no ambition to become anyone’s photographer.

Why is it important for them to show there here at the matsuri?

They are proudly radiating their presence and power in relation to the festival and territorial boundaries but also to the community in general, especially wearing their ‘hanten’ or only a ‘fundoshi’, showing their tattoos in public. There is also a great expectation from the audience and many gather to see this extraordinary spectacle for themselves. Especially the climbing, standing or riding the mikoshi which is strictly prohibited conveys an overwhelming energy between the ujiko and the crowd.

It is forbidden to undress and show tattoos in Sanja, your photos show the opposite. What is the reality of this ban?

To the best of my knowledge, the display of tattoos is undesirable and generally controversial in many places. At the Sanja festival the situation is reversed. It has always been more a rule rather than an exception to display tattoos openly. For this reason, for many people it is one of the best places to see “horimono” in real. I am also aware that outside the festival these men usually hide or cover their tattoos in public and show them exclusively in private settings, for instance, in their own special bath houses, local restaurants, bars or hot springs of choice.

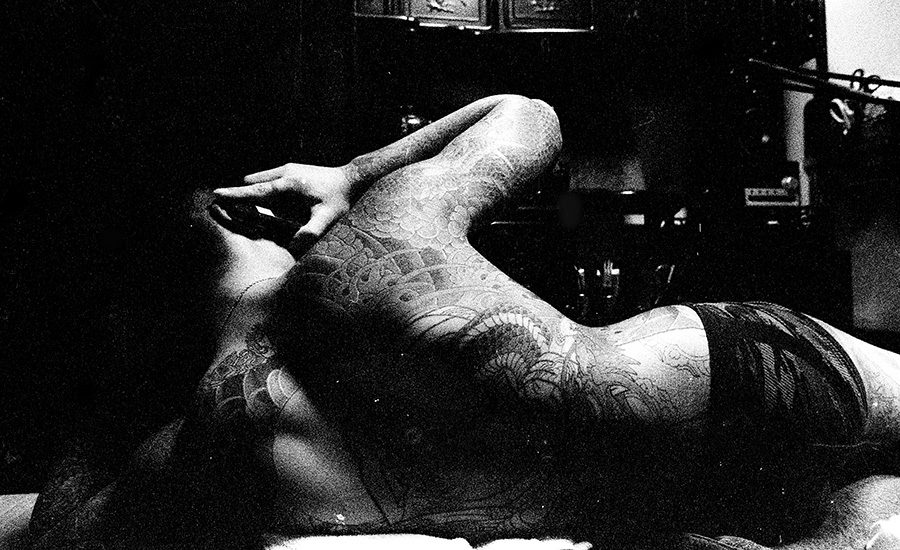

The images taken in the middle of the tattoo blend, surprisingly, with others of your privacy, taken in the Tokyo night, like an echo to the Yoshiwara pleasure district souvenir. What was your intention to ?

If the reference is made to the (female) nudity in my pictures, these women are not prostitutes. Understandably, I visited a variety of colourful establishments, with hostesses and the like. However, women in my pictures are either personal friends posing or other more random encounters.

Photographing is necessarily a physical experience ?

It is an instinctive experience.

The are-bure-boke esthetic (a rough, blurry, defocused photographic aesthetic) refers to Japanese photography from the late 1960s. Associated with these images tattooed yakuza's popular in the past - now that they've decided to fade into society, would you say Asakusa is a nostalgic book?

In my experience, contrary to the efforts of the government to suppress it, the tradition of Japanese tattoo is very much alive and celebrated all over the world. Perhaps, the way and the place I worked embrace the nostalgic spirit of modern Tokyo.

Does this adventure continue today?

As of the pandemic I have not been able to travel much. At the moment I am working on other projects, which require my full attention. Nevertheless, one thing is definite: Japan, its culture and people will always be a part of my work, either with a focus on traditional Japanese tattoo or something completely different. + IG: @ronin_de_goede Zen Foto Gallery : https://zen-foto.jp/en/book/asakusa