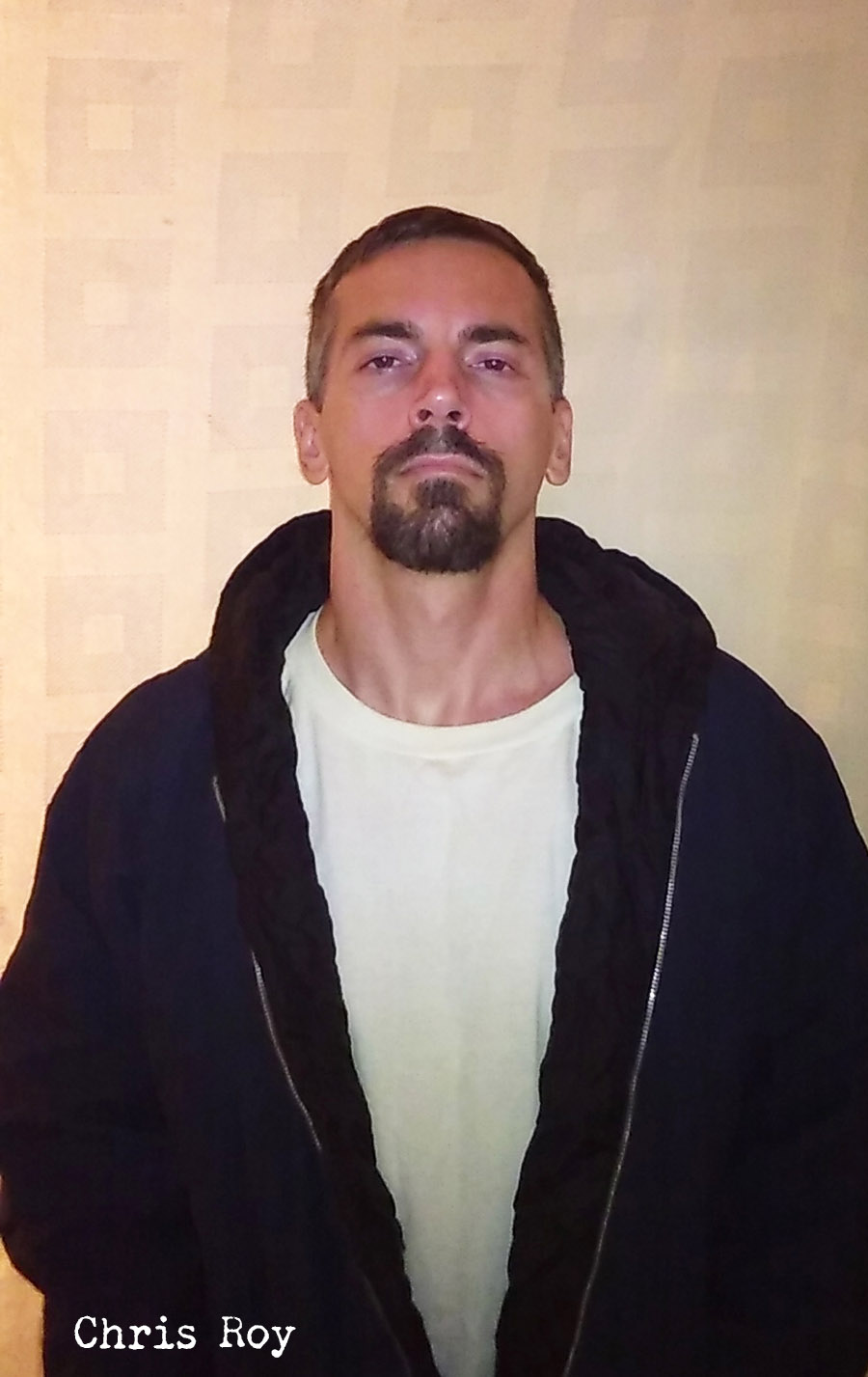

Chris Roy, convicted for murder at age twenty, has been incarcerated in a super max jail in Mississippi since 2001. Roy is Parchman Prison’s tattoo artist – the man who inks fellow inmates through cell bars with equipment made from next to nothing. His epic life journey from juvenile drug dealer to tattooist in one of the USA’s most brutal prisons is one of ruthlessness and bad luck, struggle and neglect, tenacity and discipline.

Text: Tom Vater Photos: Chris Roy

“I get along with the vast majority of guys I tattoo. But I have done plenty of tattoos on guys that I have no respect for, guys I've had deadly encounters with, and, if the situation had been reversed they would likely have tried to scar me or infect me with the viruses available on every zone… or tattooed a “Fuck you” on my back.” I have been in touch with Chris Roy for more than three years now. Like me, he writes crime novels. But it is his career as a tattooist, a brilliant meditation on incarceration and identity, which drew me to his story. “I was raised in the midst of ugly Gulf Coast beaches, thieving in communities of both rich and poor. Mom was an awesome Mom, but she had no help. It's no excuse, but that's why I began stealing and dealing - from and to the popular people with all the money.” From the age of twelve, Roy started to work as a mechanic, first fixing his friends’ go-carts and dirt bikes for free, then working at his uncle’s salvage yard. But he didn’t last. “I couldn't stand that adult mechanics who learned from me were being paid way more, and I needed better pay since my mother kicked me out. I left home with a motorcycle, jeep, boat, a pocket full of drugs and $600.”

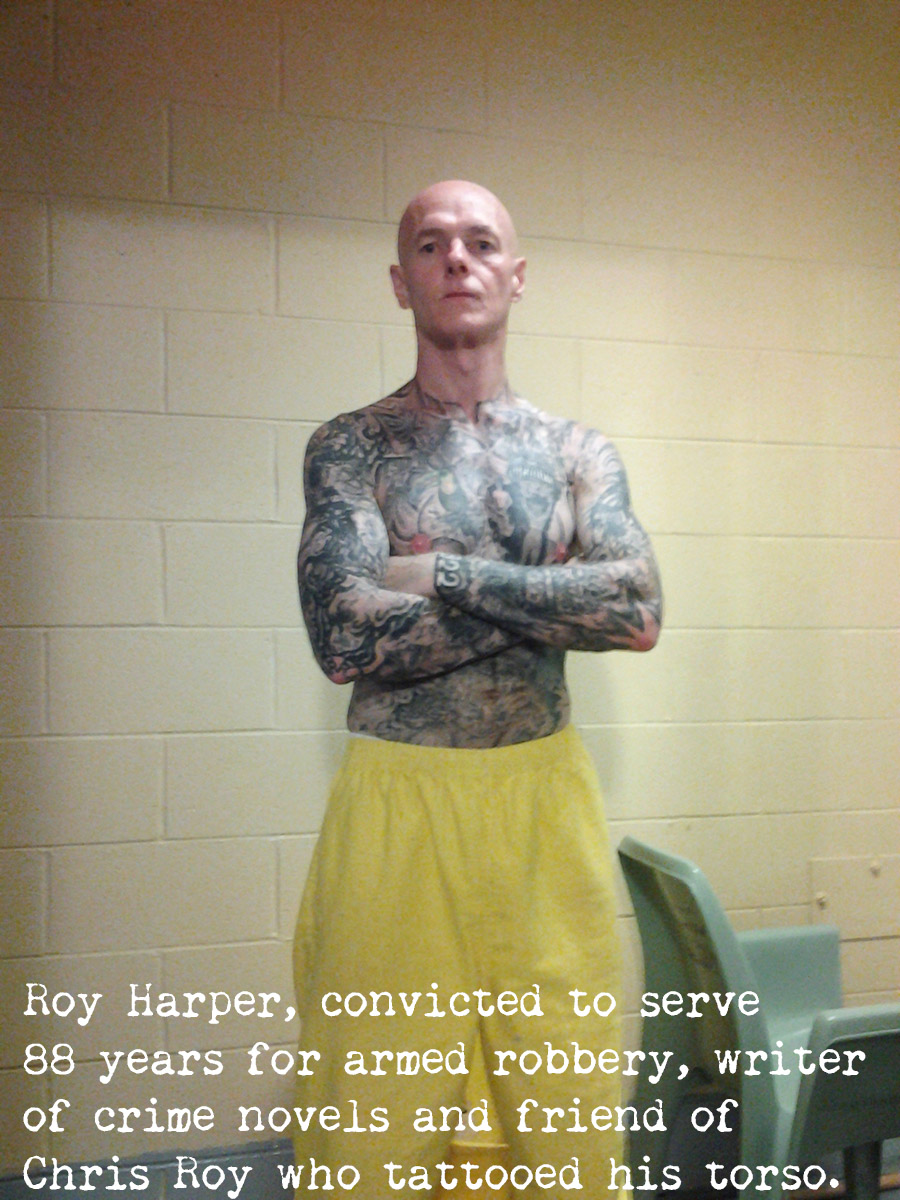

By the time he was seventeen, Roy sold stolen or found goods and had spent time in a juvenile detention centre and a state military training school. He’d also trained in Taekwondo, kickboxing and boxing since the age of ten. Roy started with a school friend, Dong, the leader of the 211, a notorious Vietnamese gang in Biloxi, Mississippi. “Dong was the main supplier to guys like me. He was an arrogant, violent dude, known for carrying weapons. After nearly two years of making a bunch of money, Dong and I had a huge misunderstanding. Our last encounter turned into a fight. I jumped him before he could pull a weapon. I knocked him out and he suffocated. I was really scared the 211 would retaliate, so I buried him.” Roy was eighteen. Two years later, in October 2001, he was convicted of murder. In Mississippi that meant death or life without parole. “My crime, the result of a fist fight, would have been a manslaughter conviction with any attorney other than the public defender I was stuck with.”

The law is against Roy, who although guilty, got sentenced in an era when violent criminals were handed extraordinarily harsh prison terms. Pre-1995 murder convictions became eligible for parole after ten years. Convictions like Roy’s, handed down between 1995 and 2014, become eligible for parole when the convict turns 65. Someone convicted of murder today will get out decades before Chris Roy, who is not due to have his appeal heard until 2047. After a couple of years in lockdown at Parchman’s Supermax Unit 32, Roy was transferred to General Population in the East Mississippi Correctional Facility. “I met this guy called Tattoo in 2003. He’d been a tattoo artist out west for twenty years and he tattooed like a surgeon on amphetamines. He could construct a precision spec machine out of pens, cigarette lighters and radio parts in the time most people drink a beer. He was an arrogant asshole. But he became my kind of asshole, and after a couple years of black eyes and cracked ribs, he became a friend.”

Roy’s cell mate Gene talked Tattoo into lending Roy his machine for the night. “The machine instantly became an appendage through which I could extend my senses. I could feel the suction and discharge of the ink, the minute vibration of the needle pumping and staining. I could sense that sweet spot depth of penetration that varies from thick to thin skin...” The first tattoo Roy did was a rabbit with fangs, a cowboy hat and a double barrel shotgun. “I remember guys at breakfast the next day, seeing the homicidal bunny. They all lined up to let me practice on them. That day, my life changed.”

Roy set his cell up like a tattoo studio, the walls covered in pages from motorcycle and tattoo magazines and original flash art. “I had medical supplies from the clinic. Free world inks. Even had a couple apprentices doing the grunt work. There was an endless line of customers in the thousand man facility. I've done lots of chest and back pieces, side and stomach, - and most of these were big, bad motherfuckers.”

Roy himself is not tattooed, “If I had tattoos I would go mad from obsessing over ways I could have done them differently or better.” Naturally, prison authorities don't like their inmates inking each other. Some prisoners get serious infections, and gang tattoos have far reaching consequences for young inmates. But the US prison system and its employees are also inherently lazy and corrupt. “I did tattoos on two guards and a male nurse. In return I was allowed to go into the clinic and get all the supplies I needed: latex gloves, ointment, iodine, even alcohol. The Chief of CID would escort me to any zone in the prison for 20US$ and leave me to tattoo. I made about $10 an hour. We were tattooing all night, smoking weed, jamming rock, fantasizing about what we would do once free.”

For a moment, it looked like Roy had carved out a life of sorts. “I had a tattoo business that made money. I had an excellent job working for the Education Department teaching math and English in GED classes. I had a group of guys I trained in boxing and I enjoyed building props for plays. But every day, without fail, I planned to escape.” In 2005, Roy made a break that was straight from a movie, sawing through the bars in his cell window with a hack saw. But once outside, plans went awry and he was caught within 24 hours. Shortly after, he escaped a second time. And got caught once again and returned to Parchman. For the next three years, Roy didn’t have a single opportunity to tattoo. “I experienced the worst living conditions imaginable. Now a high risk prisoner, I was moved to a different cell every week. I was strip-searched and put in restraint gear every time I came out of the cell - even to the shower and yard cages. There were psych patients screaming, throwing feces, setting fires and flooding their cells. It was hell. I knew I would have to live like this for years. But that brief moment of freedom, the memory of it, made it worth it.”

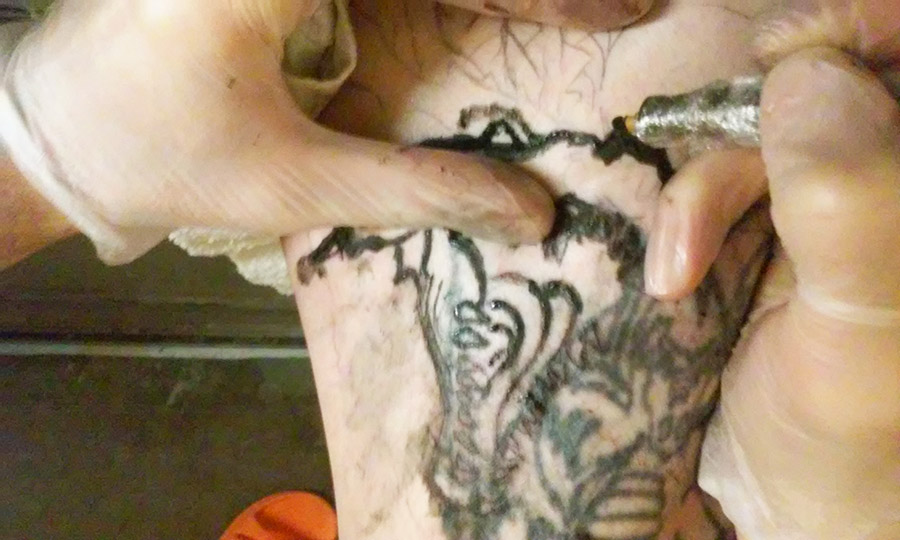

Things changed in 2008, when Roy qualified for a high risk incentive program. “We had to figure out a way to tattoo while being watched on camera. We had this big rolling telephone, basically a huge crate on wheels, outside the cells. The customer would roll the phone crate in front of my cell, sit down on it, hold the handset to his ear, pretending to make a call, and stick his other arm into my cell. The phone blocked the camera's view.” The hardest inmates to tattoo are those on death row. Kept on their own tier at Parchman, these men are almost impossible to reach. Contact with staff or other inmates is strictly forbidden. “We made history when my friend D-Block paid an officer to allow me to tattoo him through his bars. It was expensive, but it was worth it. He showed off my work outside in the yard cages to others on death row. Nearly everyone wanted me to tattoo them, but they couldn't afford to grease the right palms.” Roy managed to tattoo D-block six times.

“I also got friendly with a guy called Ben. He is up for capital murder and it’s not looking good for him. I put pictures of his wife, his daughter and his granddaughter on his back along with a winged horse and a goblin skull. I must have been up to his cell twelve times. But Ben suffered from paranoia and delusions. We fell out and he burned me for 500$.”

In November 2016, Roy was caught with a mobile phone and was taken out of the high risk incentive program. He spent ten months in a cell with a steel door in almost complete isolation and could no longer tattoo. “I thought a lot about tattooing then. It’s what keeps me sane in here.” Since he is back in his old block, he pursues the activity that puts him at the centre of his community and has tattooed a couple of large side pieces. Through the bars of his cell of course. For more information on Chris Roy and his case, visit https://unjustelement.com/

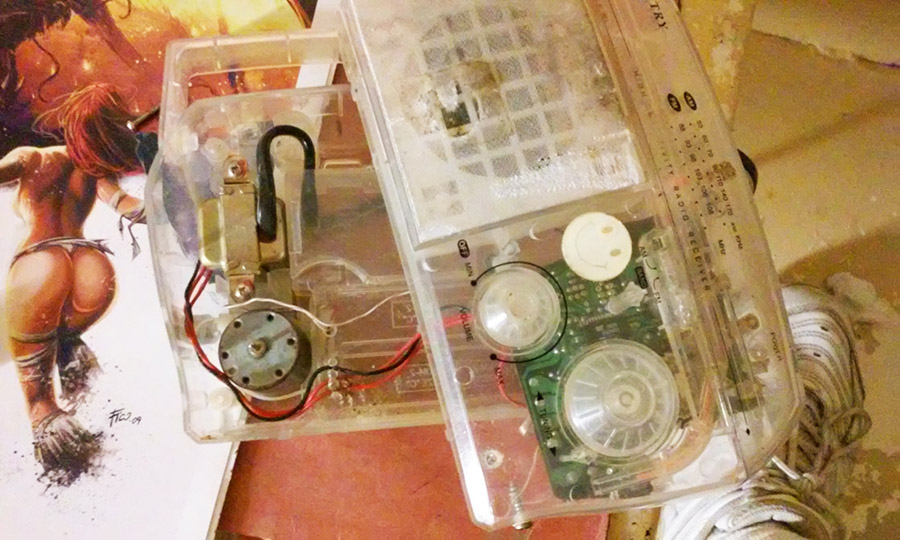

Build a tattoo machine in an American maximum security prison

Roy didn’t have much to work with to build his tattoo machine in Parchman maximum security - a prison issued radio, a Bic lighter, a clear Bic pen body, an empty ink cartridge, a ballpoint tip, the rubber body of a security flex pen, the plastic top of a chemical spray bottle, and a small square of rubber.

“First I remove the ballpoint and replace it with the jet from the Bic lighter. Then I cut a small section of the flex pen body to insert into the motor end of the cut down Bic pen. This will hold the tube securely in the centre. The spray bottle top is a perfect motor mount. I cut it a little to slide it onto the Bic pen body. This makes adjusting the needle depth easy. Then I cut off the ballpoint and insert the jet from the lighter into the plastic tip. The square of rubber needs to fit onto the motor shaft. I poke a hole into the rubber next to the shaft and insert a small cut of insulation from telephone wire, the sleeve for the needle. The needle then fits into the piece of insulation. I then place the needle, the tip, the guide (the former ink cartridge), the ink cap (a soda pop top) and a wipe rag (a piece of t-shirt) in a bowl of water and boil it in a microwave for three minutes. Finally, the motor is secured to the mount with a rubber band and the machine is wrapped in Saran wrap.”

Producing ink also took some creative and unconventional thinking.

“I remove the blades from a couple of plastic shavers and tape the bodies together with salvaged tape. I glue a piece of A4 paper with toothpaste into a circular smokehouse that will collect soot. The shavers go in the centre and I set fire to the plastic heads. I cover the smokehouse with another piece of paper underneath a magazine. The paper will turn to soot which I collect in a bottle top. Burning two shavers makes enough ink for a very large tattoo. Mixing the ink is an art in itself. I put water in a plastic bottle cap, then a couple micro drops of shampoo. I sprinkle the soot in a little at a time. Too much shampoo and the detergents will make the tattoo blue or green. Too much soot and the ink will not work in the machine's suction and discharge.”

The final necessary tool is a decent needle.

“I heat the spring from the lighter with a slow burning flame off tightly rolled toilet paper. I move the spring through the flame while I apply steady pressure, pulling it straight as I move it. If I pull too hard, it'll snap. If it gets too hot, it'll break.”