Reputed for his modern images done in the ukiyo-e style, the talented Japanese illustrator Mitomo Horihiro showed an identical care in the history of the tattoo culture since he got back behind the needles at the studio Three Tides, between the cities of Tokyo and Osaka. Very much concerned about keeping the pure authenticity of the wabori, the young tattooer went back to the roots of the craft in a radical way: he not only decided to work entirely by hand, but also to source his artistic inspiration to go straight back to two godfathers of traditional japanese tattooing : Horiuno I and Horiuno II.

Japanese tattooing is known under different names (irezumi, horimono, shisei…), each one having its specific meaning, but you prefer the term wabori. Why ?

Initially, it would be called horimono. But, with western tattooing arriving and in order to make a distinction with japanese tattooing, we started in Japan to use the word wabori. For me, it is an irezumi born here and which consists to tattoo by hand after drawing the motif on the body. It has a certain popularity in the end of the Edo era (1603-1868) and the beginning of the Meiji era (1868-1912). It stays until the end of the Taisho era (1912-1926), until tattooers start to use the western electric machine imported from abroad. The rendering is not the same when the tattoo is done with this device. The differences are about the same between a Bic pen and a brush. It is possible to do straight regular lines with a pen when the thickness of the lines varies with a brush It has a specific « taste », that we call aji in Japan. What do you mean by this idea of « taste» ? It is a term we use for the food too in Japan. In the case of these images, when they are done with a machine, there is a linearity; everything is standard and flat, without originality. To the opposite, the ones produced by hand are all different, each one of them having its own specific variations and nuances. They have that « taste », they have aji. Let’s take an example with the pictures that I draw. I don’t use a pen but a hude, a brush that I deep in ink. The lines that I draw on paper with this tool are not regular, they have a personality. It’s the same for tattooing. In that matter, I want to draw directly on the body and not to use stencils – I consider it as a copy. Free-hand has also an other advantage, it’s easier to adjust the design to the specific shapes of the body.

You did not always worked by hand, you learnt and started to tattoo with a machine. How did you develop your appreciation of this « taste » ?

One day I understood there were no difference between the old wabori and what I was doing. I couldn’t exactly point it but I knew there was something. During a trip to New-York, I had the chance to meet japanese tattooer Horizakura, from the Horitoshi family in Tokyo. He learnt from his master, Horitoshi 1, an unconventionnal technique : the electric machine to trace the lines and the hand technique known as tebori to do the shading. When I looked very carefully at his work, the colours of his tattoos appeared much brighter. It appeared obvious to me: I had to use this technique.

How did your apprenticeship happened ?

I learnt by looking a little bit at Shinji (Horizakura) while he was working, and then, once back in Japan, I studied on my own. It’s a familiar process. I already experimented it when I started doing illustration ; I’m a complete self-taught man. Thus, I wasn’t really worried. I thought about going to see one master from which learn the technique, but after a few researches I realised the artists I admired the most and from who I would have loved to learn, had passed away. Who are they ? There are two major books dealing with the topic of tattoo in Japan : Bunshin Hyakushi and Irezumi Taikan. They show the work of oldtimers active during the Meiji and the Taisho eras, like Horiuno I (1842-1927). When I first saw his drawings I thought they were a little bit childish, too much simple, minimalistics ; I was not very much interested in them. I liked very much the ukiyo-e style, but when it is more mature, more detailed. Progressively, I understood their own true nature. These drawings were deliberately purified, simplified, in order to match the requirements of tattooing by hand. These drawings had been done to be tattooed. It is important to understand that it is not possible to produce a detailed work using the tebori technique. Horiuno I, but also Horiuno II (1877- 1958), showed their ability to concentrate on what was the most important. In this way, their drawings would become references from which I could learn, before copying them. It’s been a year now that I concentrate exclusively on studying the work of Horiuno I and Horiuno II.

How important are these tattooers in the history of japanese tattooing ?

If you refer to the archives available today, and if you had to build a pyramid, Horiuno I would be at the top of it. He would be at the highest position in term of value. He was himself influenced by other tattoo masters of his time – Horikane and Horiiwa- but there are no archives available recording their work. You can find older archives than Horiuno I, but these are mainly coloured or modified pictures ; it is difficult to have a clear idea of the rendring at that time. Moreover, we know that during his time, Horiuno I was the most renowned tattooer in the city of Edo (former Tokyo). He was born there, in the Kanda district. But Horiuno II is at a very high position in this pyramid too, and none of them ever used the electric machine.

By taking inspiration from these two tattooers, what is your goal ?

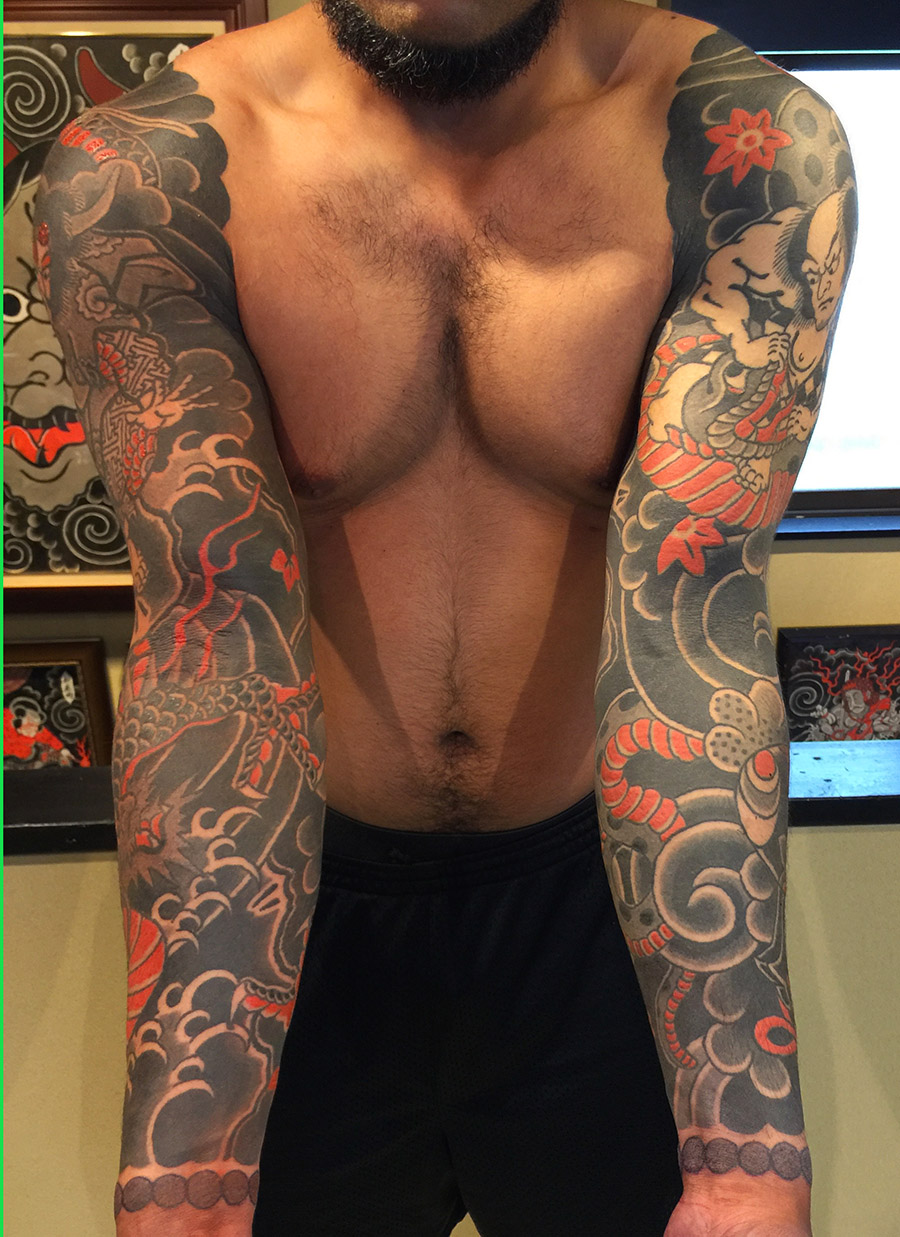

I want to use their style, to protect it, and strengthen it ; but I want also to innovate and then do an even better tattoo. I still don’t know what it will look like, I don’t have a clear vision yet of that goal, but I’m actually learning and growing. I take what I like the most from both of these two tattooers. What are the strong points of their works ? I like their backgrounds. They are solid, without bokashi (shading). It is particularly true with Horiuno I’s work. Lately, Horiuno II will adopt very smooth shading. These black backgrounds are strongly highlighting the main subject. It gives more readability to the compositions too, in comparison with tattoos using more shading. The eyes are not solicited at the same time and at different places. Compositions are more balanced, I like it. According to me, Horiuno I was a better drawer. I prefer his style, stronger and not as pop as Horiuno II’s, who lacks a bit of constancy too. It can be partly explained by the fact he’s lacking experience. Horiuno II was 45 years old when he started tattooing. Horiuno I was in his twenties. His career spans over a period of more than 50 years. It is a great inspiration for me.

These tattoos use very few colours. How difficult was it for you, who shows strong colour skills in your illustrations ?

Only two colours were traditionally used in tattooing : black and red. When I started I used to do on skin what I was doing on paper. But I was not satisfied, the colours would not pop up as much as I would expect. Progressively, I made a distinction. With too many colours, the picture loses strength. Therefore I chose to reduce my colour palette. You combine modern elements with the ukiyo-e style in your illustrations. Is it something that you would do, in your wabori ? I hate introducing modern motifs in tattooing, so we can say that the classic iconography of wabori is fixed. In an interview, Horiuno I says that he doesn’t want to represent horrible or scarring things, like ghosts ; consequently, I don’t do it either and I consider there should not be such things in wabori. The archives about these tattooers are very limited but I try to go over these limitations by developing my skills and my knowledge. We know, for example that, according to some of Horiuno I’s sketchbooks, and even though I didn’t have the opportunity to have it in my own hands, his drawings have been inspired from prints of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (one of the most famous artist of the ukiyo-e movement) of the Suikoden (famous Chinese novel which sparkled the explosion of tattoo in the 19th century in Edo). Therefore, I can suppose he did other drawings from this series that I can introduce in my work.

These tattooers had a different approach to their material, they would build their own tools.

I do the same and I use the same material. It is one of the specificities of my work. I use nomi –the sticks to which the needles are attached- as tall as the ones used by Horiuno II. I mix pigments myself and developed my own little secrets. I use old needles, they are 50 years old at the minimum. They are taller than the ones used for the electric machine, but they’re identical to the ones used by Horiuno I. I sharp them by myself, something that I’m probably the only one to do. But, the way they’re mounted on the nomi is probably different. It belongs to the artist’s secrets and there is very little information available about these tools. But, I can still make suppositions. How important this research of authenticity is important to you ? It’s a matter of pride. When it comes to wabori, you “have to” do the things by yourself. Building your own material, making your own ink, working by hand, this is wabori. It is a matter of passion, of heart. CONTACT : IG : @horihiro_mitomo https://www.hiroshihirakawa.com http://www.threetidestattoo.com