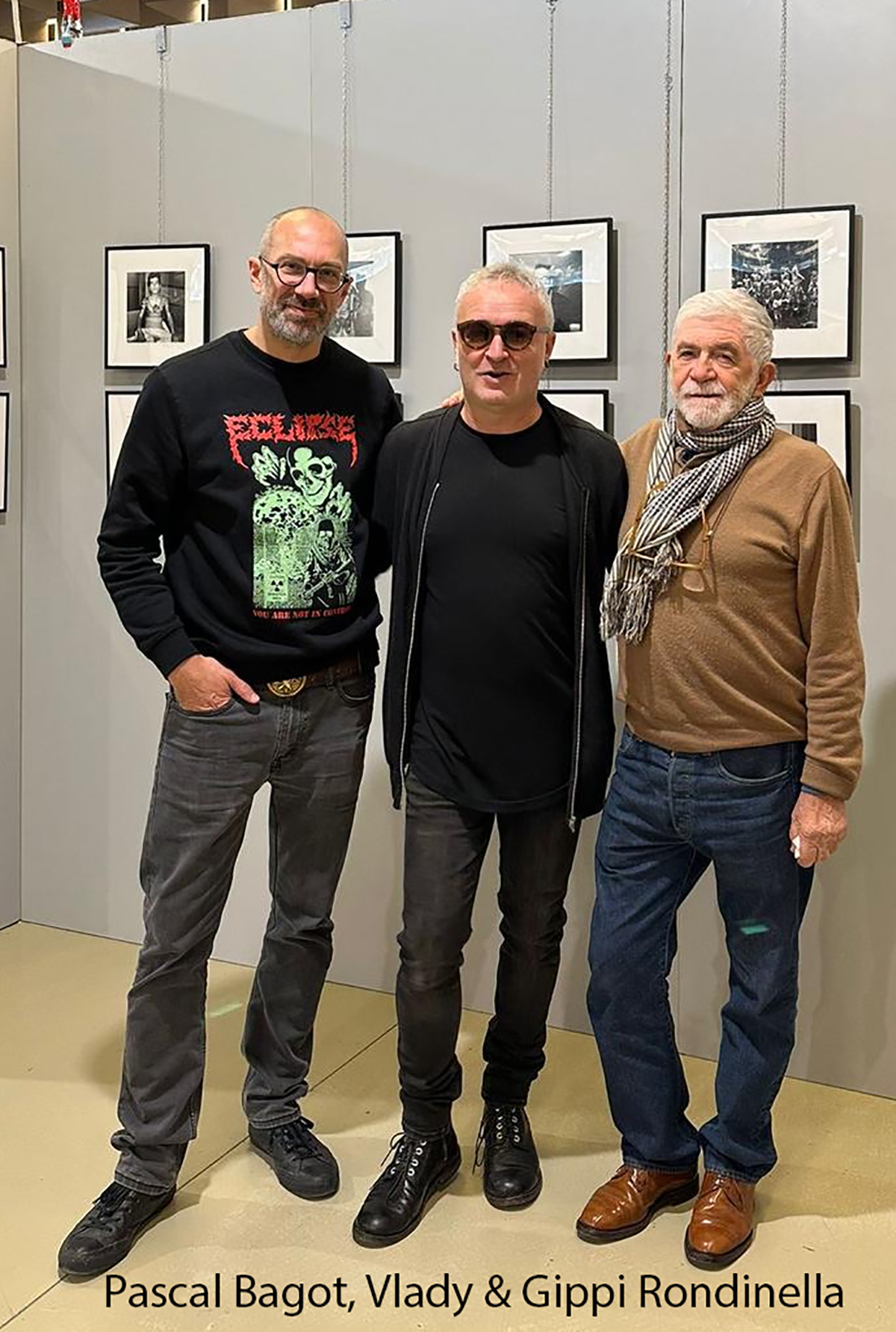

Gippi Rondinella is what we call a pioneer. Following in the footsteps of Marco Pisa, a tattooist from Bologna, he opened one of the very first professional studios in Italy: Tattooing Demon, in Rome in March 1986. This landmark in the history of modern European tattooing is the fruit of an adventure that began in the 1970s, thousands of miles away, on the "hippie trail". Like some of Europe's youth, also in search of something different and meaningful, Gippi set off on the roads of Asia. In the Mecca of backpackers, Kathmandu, he adopted a tattoo and forever marked his body with his desire for freedom. Now retired and living happily ever after in Vietnam, Gippi opens up his trunk of memories and tells us a few episodes from what has become his 'tattoo trail’.

Your connection with tattooing has a lot to do with travelling. It was in Nepal that you got your first tattoo, wasn't it?

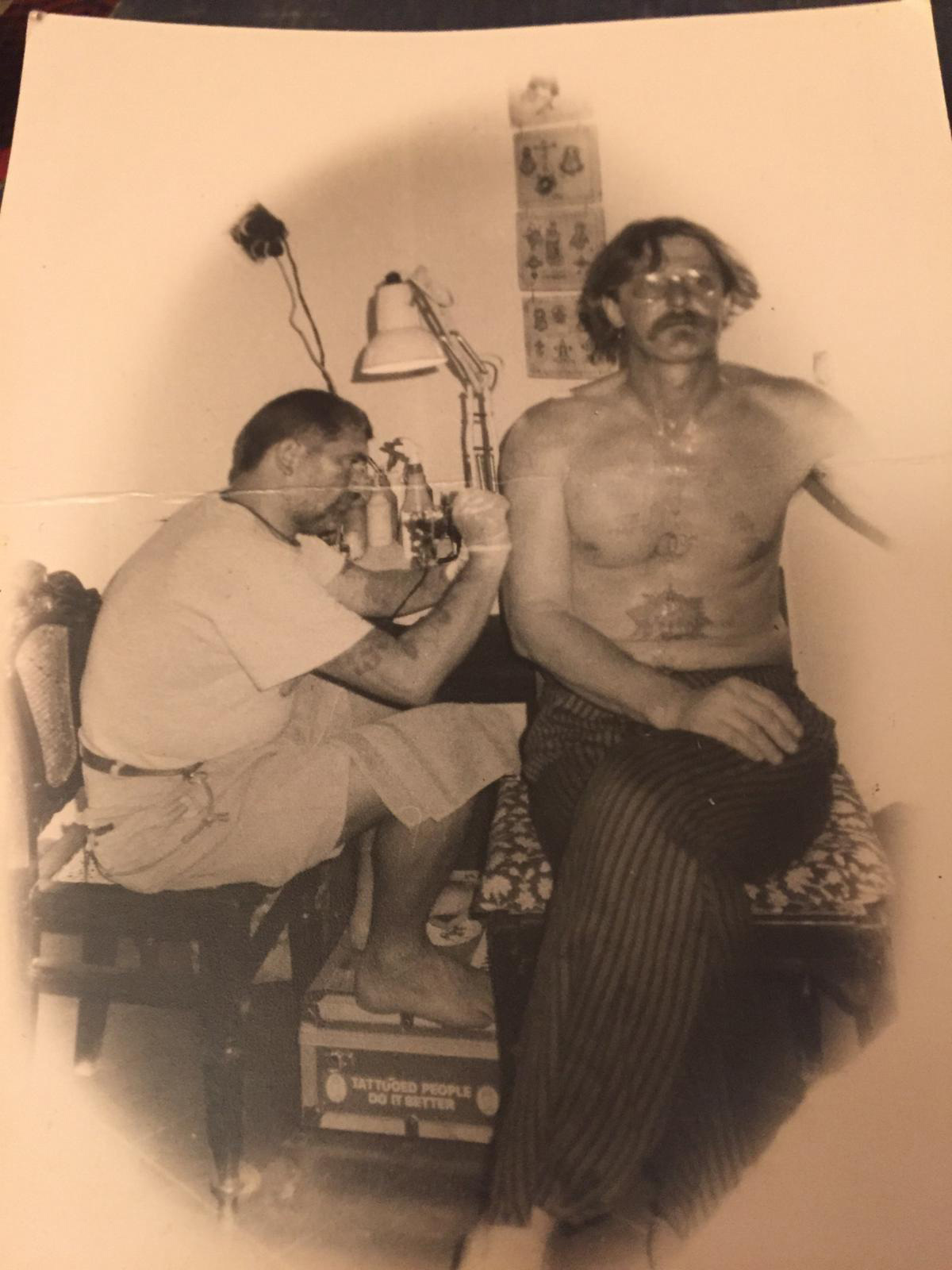

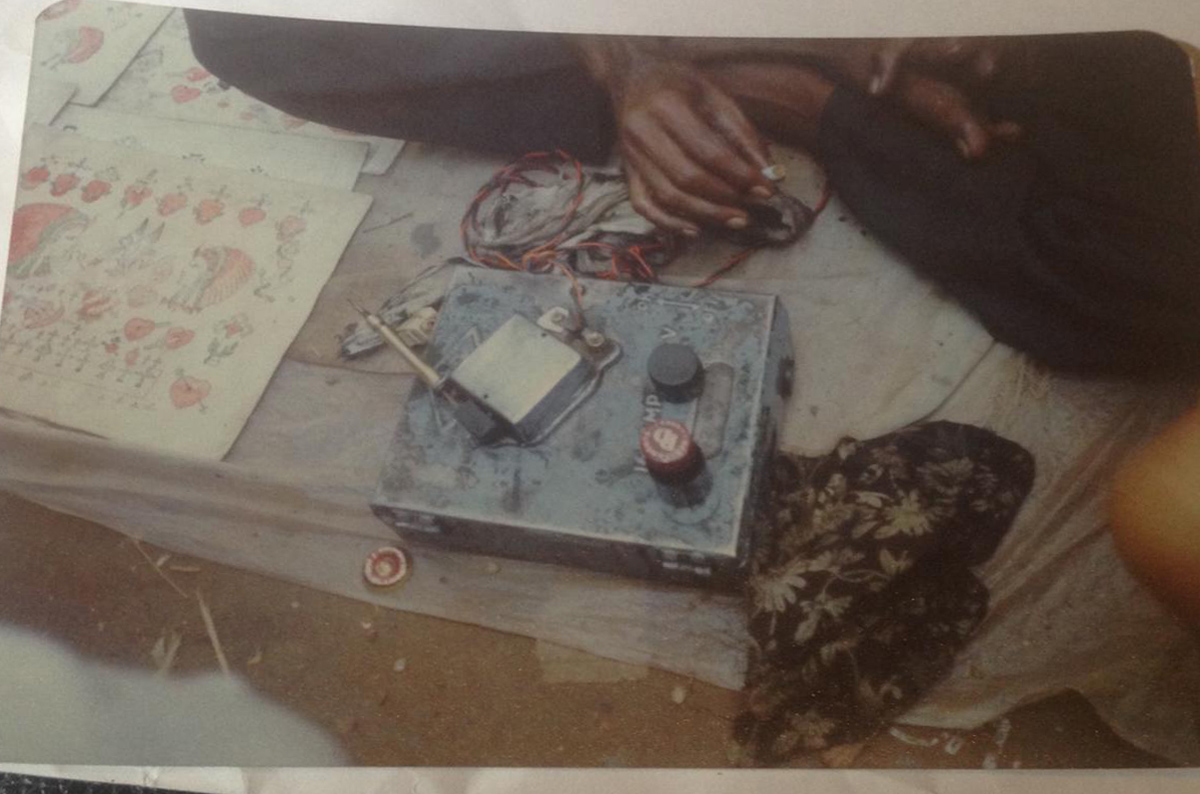

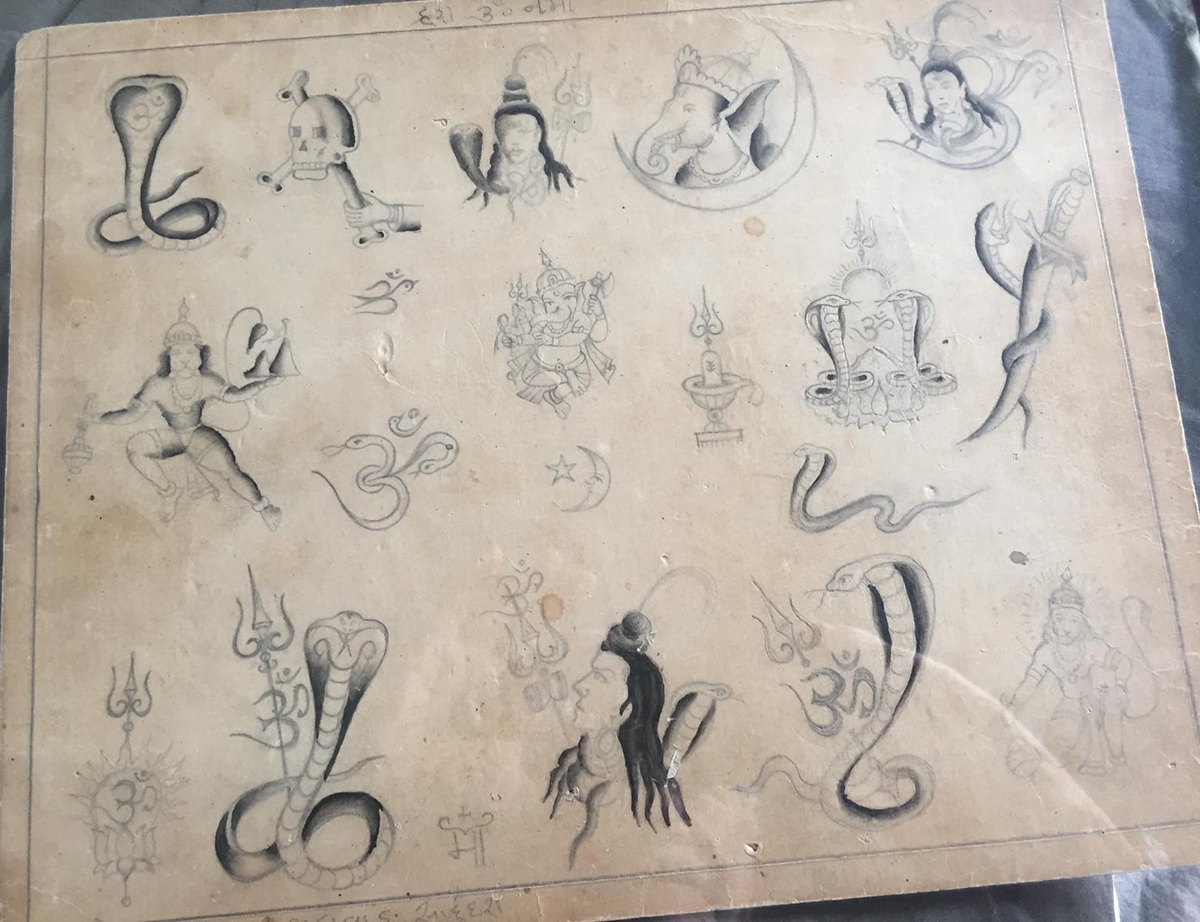

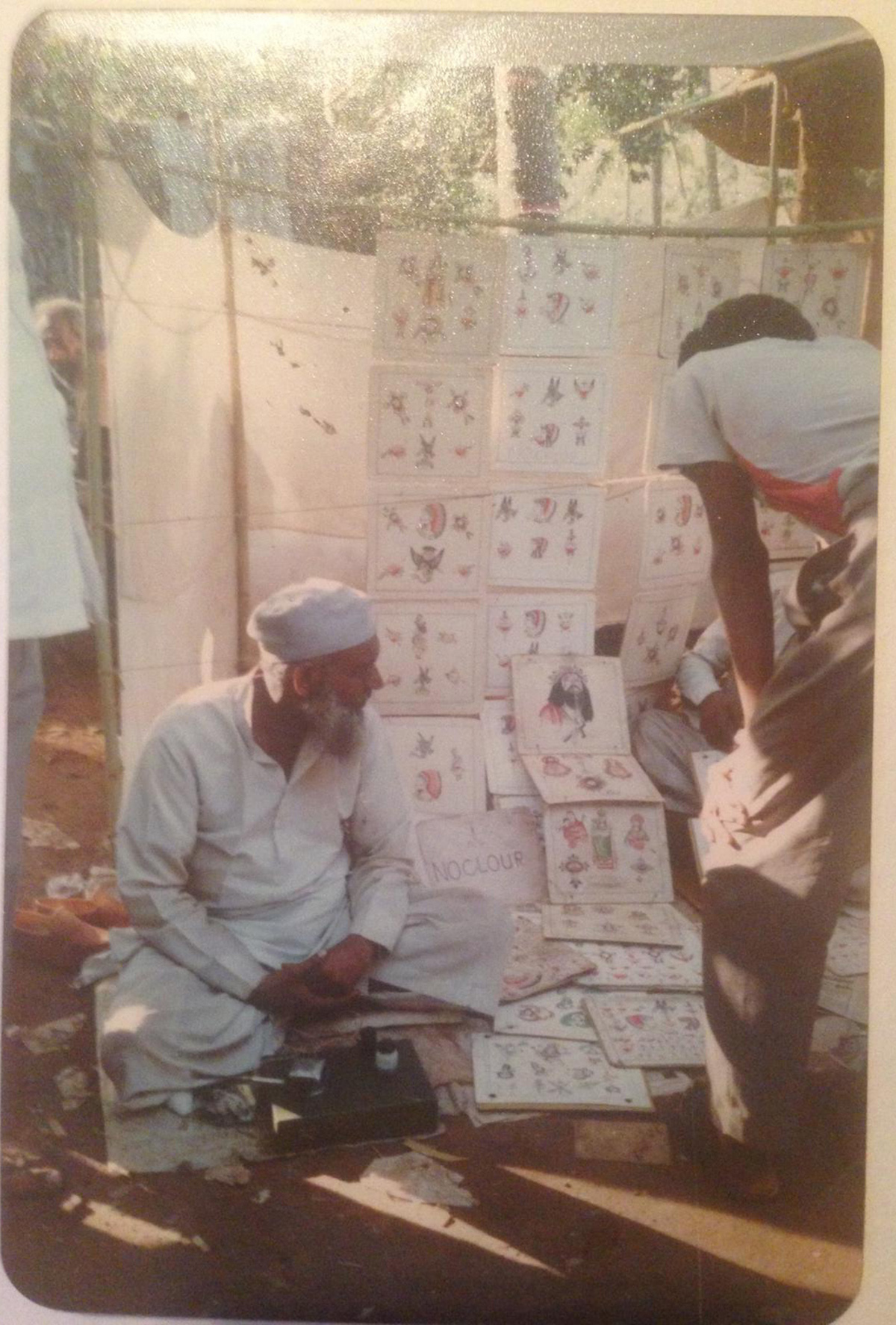

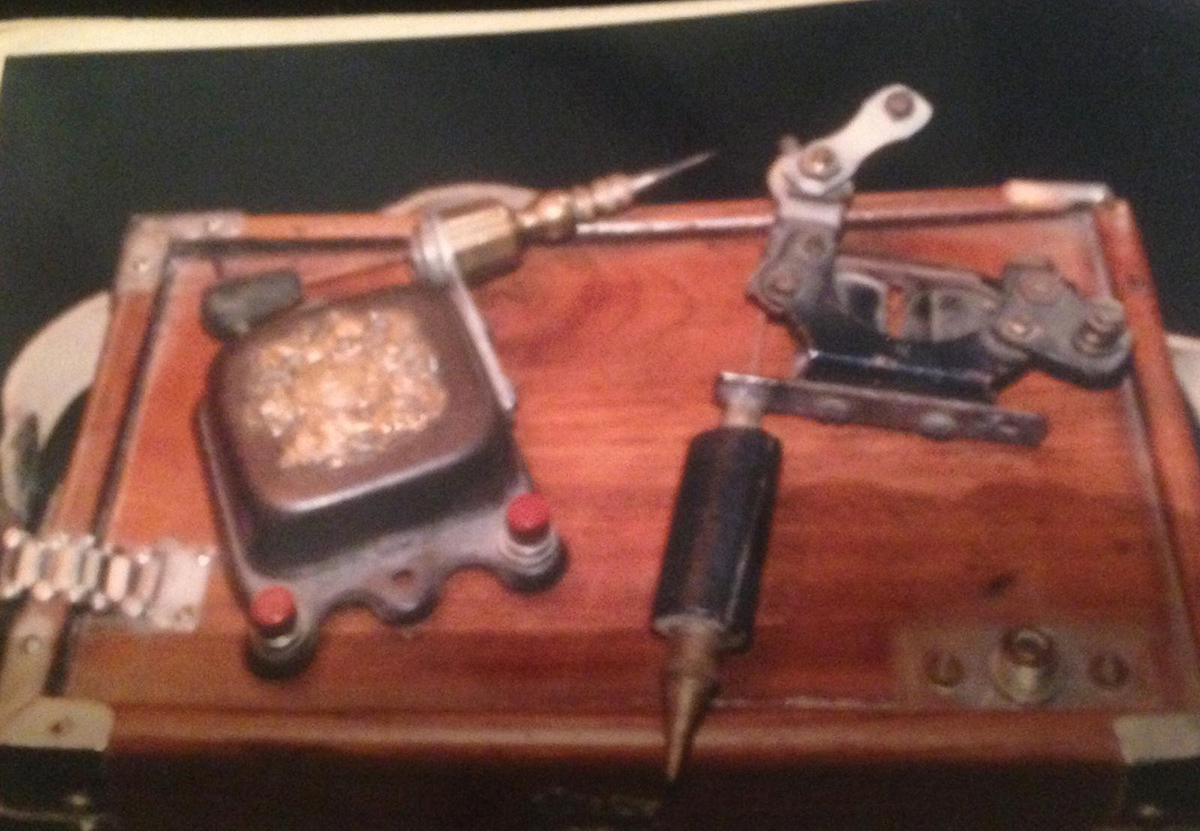

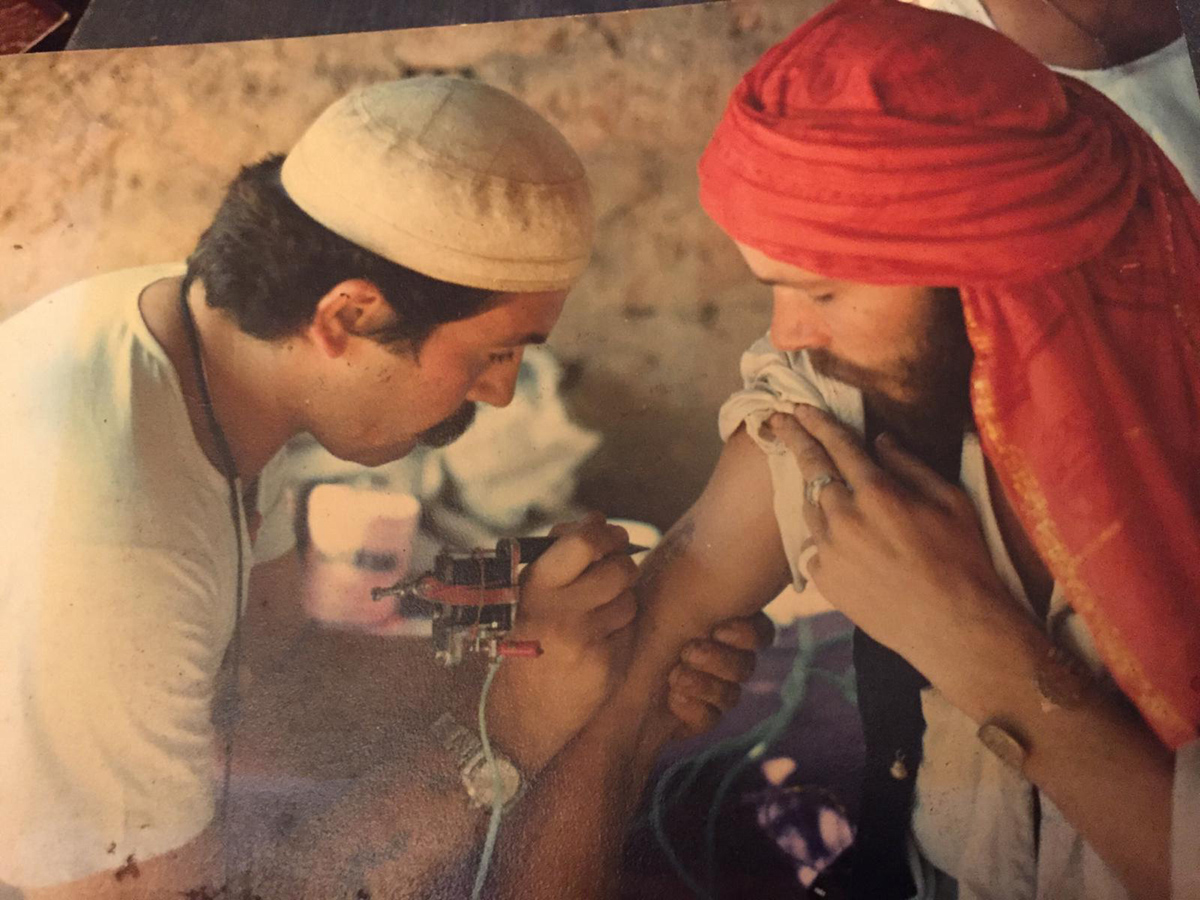

Yes, I was 20 when I got my first tattoo in 1970 on a street in Kathmandu. Five years later, I bought my first tattoo machine in India, in Goa, from one of these street tattooers. That same year, however, I started working for the airline Alitalia as a steward. I did this job until 1979.

What was the motif of your first tattoo?

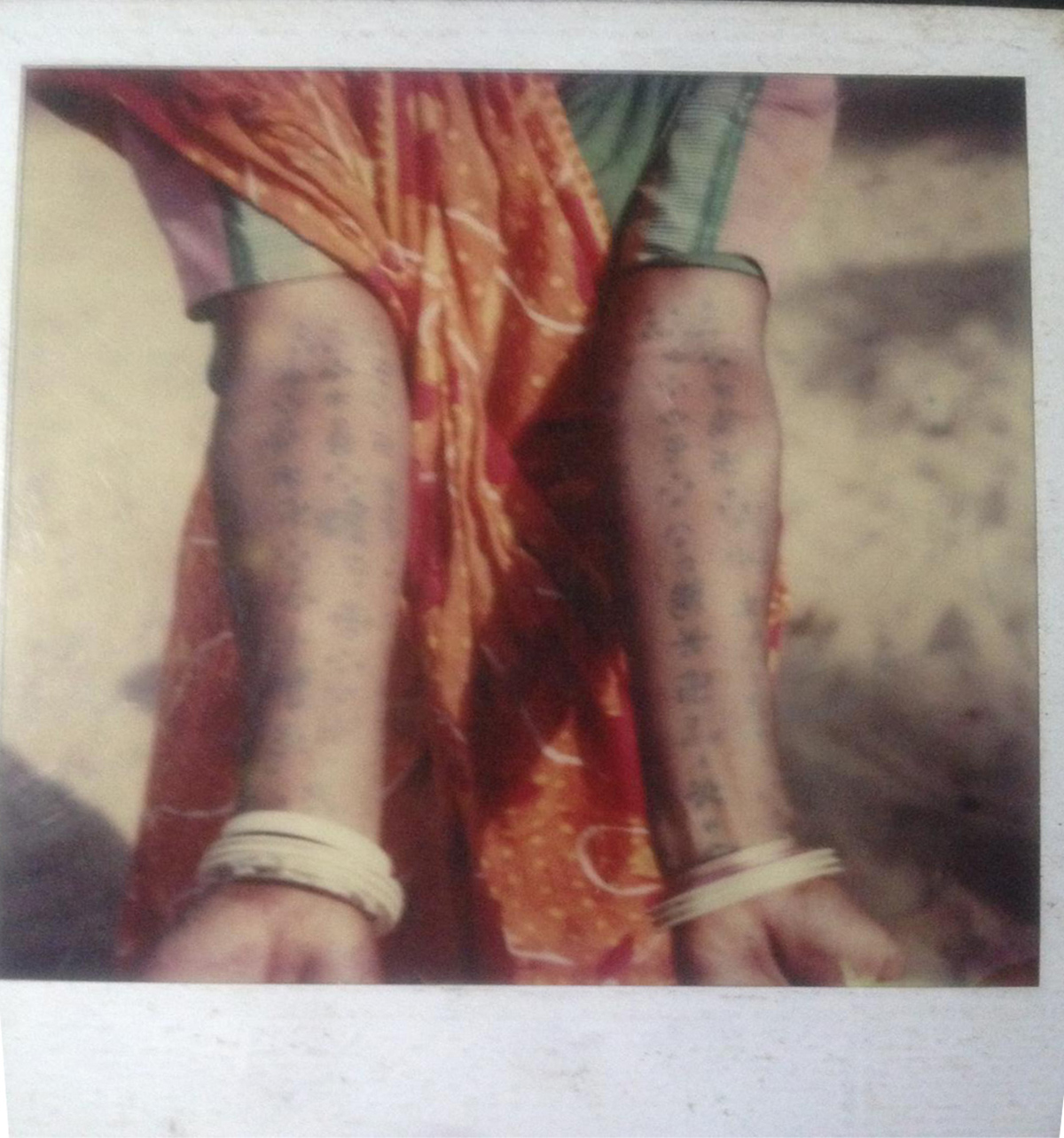

An OM, followed the next day by another representing the sign of fertility. The lines were very badly done, but that didn't stop me doing a sun the next day. I then continued to get tattoos on my travels, in Bombay, Goa, Singapore and so on.

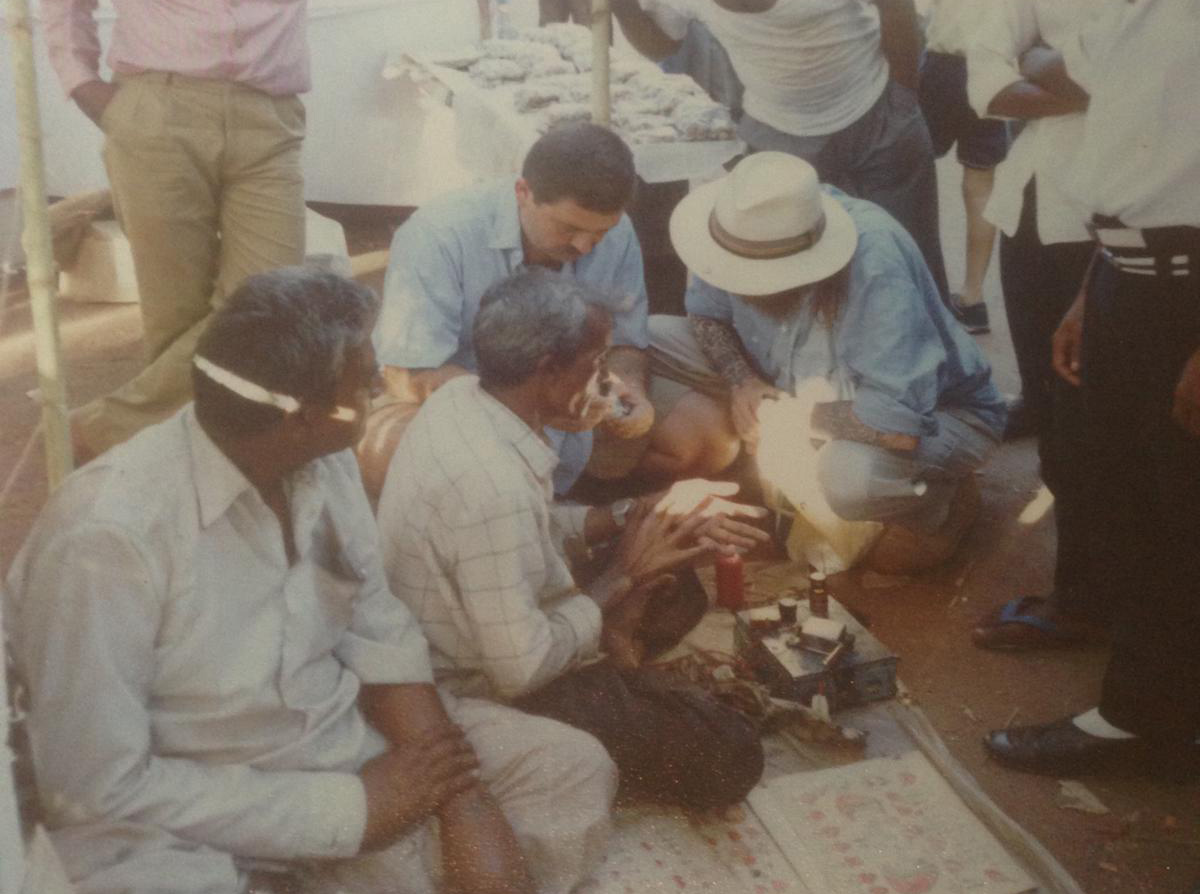

What was Goa like back then?

Goa was a crossroads for hippies, travellers and freaks. In India, you'll meet some of the leading figures in modern tattooing, including the Leu family. But also Doctor Jangoo Kohiyar.

What was your relationship with the man whom French author Stéphane Guillerme, a specialist in tattooing in India, calls "the father of modern Indian tattooing"?

I met him by chance and I don't really remember the circumstances. It was about 40/45 years ago. But Jangoo was a psychiatrist and had started tattooing for pleasure. He was in a way the 'first' professional in India. He was passionate about it. Tattooing wasn't as popular as it is today, of course, and it was primarily a religious practice. Only Christians and Hindus had their marks done, by street tattooers. Today, Jangoo is considered by the large Indian tattoo community as a father.

Before this adventure in Nepal, your first trip was to England, to London, where you left in 1966 at the age of 17. What were you doing there?

I was having fun, working in a restaurant where I cooked and washed dishes. I wanted to improve my English because I hadn't studied it at school. Well, let's just say it was an excuse to enjoy Swinging London, listen to the Beatles, Pink Floyd and take acid. It was better to have fun and do things. The following year I went to Istanbul and stayed longer.

Didn't you like your life in Rome?

I went to art school and it was boring. I went there for a few years, but sitting still in a classroom didn't suit me. I could draw, but I never considered myself an artist. Just a tattooer.

Did you get tattoos during these trips to Europe?

At the time, even in Europe, tattooing was very rudimentary. But I went to visit Bruno in his studio in 1968. Then, a few years later, in 1970 or 1971, on my return from Nepal, I was tattooed by Leslie Burchett, George Burchett's son. I was 21, and the studio was also simplistic. I met Mike Malone in 1971 or 1972 in New York, and he coloured the sun I'd had done in Kathmandu. I was also tattooed by Jock, again in London, then by Herbert Hoffman in Hamburg. I've also been to Amsterdam and Copenhagen.

What were you looking for?

I became interested in tattooing out of curiosity. At the beginning, I liked going to see the studios, wherever I could, even if I never thought I'd become one of them. I was first and foremost a hippy, a traveller and professionally a steward. Tattooing was an adventure, a lifelong souvenir, a childhood dream.

What are you trying to say?

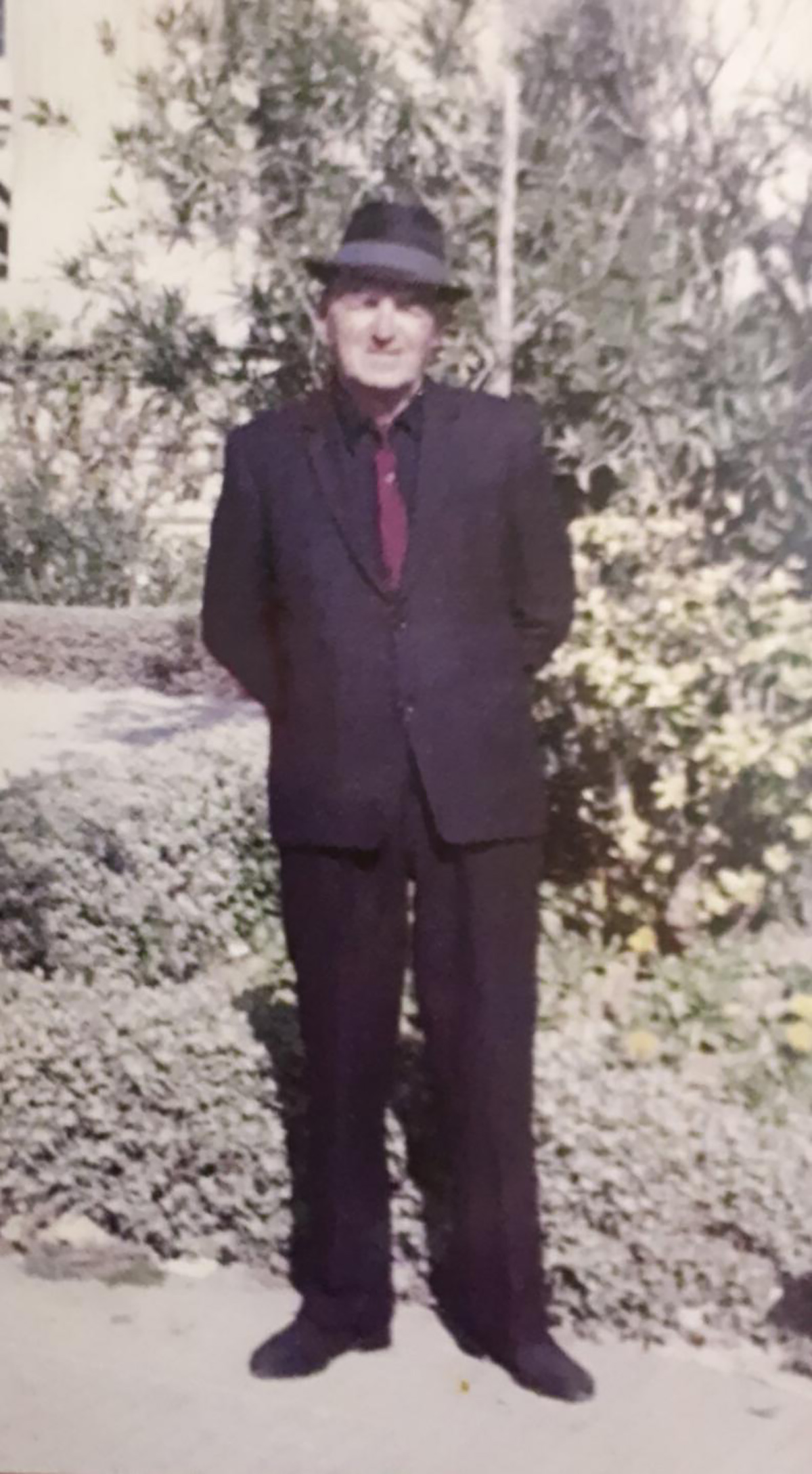

When I was a kid, my grandfather gave me access to newspapers and books. I had loads of paper in the house and I collected tattoo images whenever I could find any.

Why tattoos?

It was a souvenir from my other grandfather, who owned a small circus in the south of Italy. He was an acrobat, worked on the rope, and wore a few crude tattoos like they did in those days.

From 1979 you worked as a steward, but you started tattooing on the side when you weren't travelling. How long did this last?

Five and a half years. I used to tattoo in the centre of Rome, in a street near the Tegina Coeli central prison. I had lots of customers, but I only did it for pleasure. It was good training. Then I resigned and went off to charter in the Maldives. For three years, all I did was sail. I started tattooing again when I returned home to pay off some debts I'd incurred with the bank. I even opened a Tattoo Bar in Rome - a cocktail bar - before opening my own studio in February 1986: Tattooing Demon. I stopped in 2001 when they started tattoo schools. That was the end of a great story.

Was the Tattoo Bar a meeting place for tattooed people?

No, not really. In the early 1980s, tattooing in Rome - and in Italy - was still a fairly private affair. But things changed in 1985 with an event that took place at the Mercati di Traiano in Rome: the Asino e la Zebra. It was an exhibition set up by Ed Hardy with the help of Italian organisers. Many of the big names in the industry took part, including tattoo artists Horiyoshi III, Henk Schiffmacher, Gianmaurizio Fercioni and Dennis Cockell. It was a fantastic three weeks.

What impact did this event have in Italy?

It attracted a lot of attention and had a big impact on people. It brought to light a reality that everyone knew, but in an erroneous way. Previously, thanks to Italian and French scientists Cesare Lombroso (a 19th century Italian criminologist who saw tattoos as a visible indicator of an individual's social dangerousness) and Alexandre Lacassagne (a French doctor), tattoos had been reserved for thieves, sailors and prostitutes. Nobody knew anything about it. These three weeks put tattoos on the map and made them popular.

What equipment did you have when you started?

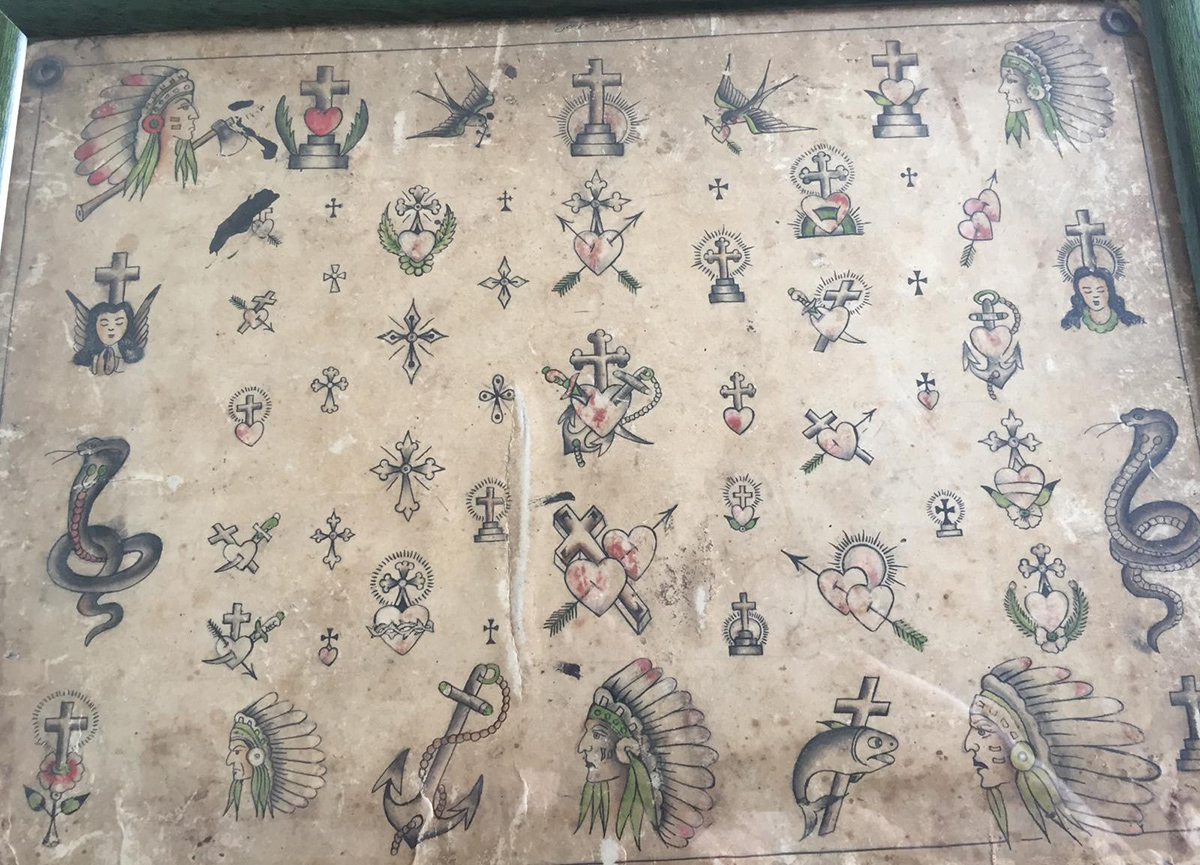

I was lucky enough to know Spaulding & Paul Rogers (an American equipment distributor) and therefore to have books, flash colours, etc. Addresses and information were hard to come by. Tattooers were a closed group who didn't like to share with strangers. Not like today with the internet.

How did you get Spaulding and Rogers' address?

I got it from an old Maltese tattooer, Charly Parnis. He's also the one who gave me my second machine, with colours and a few flashes, among other references. Charly had very classic, basic designs, Spaulding flashes, illustration books and American magazines. He also gave me a lot of advice. He was old and had stopped tattooing, but he gave me everything. Thank you Charly and respect.

The story of how we got to Charly is quite incredible. Can you tell us about it?

It all happened in 1975, when my girlfriend was a flight attendant. During a trip to Malta, she happened to meet Charly Parnis, to whom she explained that I was looking for a machine to buy. Against all odds, he accepted. On her return, my girlfriend told me all about it and I decided to catch a flight to Malta. When I arrived, I bumped into another man who told me that Charly had died in the meantime, so he couldn't sell me a machine. But, fortunately for me, I didn't believe a word he said. I had the address of his house, so I went straight there and met him.

Had you tried other ways of obtaining material before this Maltese connection?

Of course, in Denmark and France. But Bruno, in Paris, hadn't yet opened Jet France, his distribution company. And the guys in Denmark, in Nyhavn, weren't very cooperative.

Let's go back to the opening of your first studio in Rome in 1986, the first professional studio to open in the Italian capital. What made you decide to go for it?

Marco Pisa was a friend of mine at the time; he had opened the country's first professional studio in 1985 in Bologna. There were so few of us. Everyone in their own town. There were no hard feelings, no jealousy, just friends embarking on an incredible adventure.

Do you have any idea how many tattooers there were back then?

There was Marco in Bologna and three or four others all over the country. None of them were professionals, they were all amateurs. Pisa was a furniture and antiques restorer. Even Gian Maurizio Fercioni and Mino Spadaccini did other work and tattooed for pleasure and curiosity. Fercioni was in the theatre and Spadaccini in advertising. Mino was a friend of Fercioni's and both had been working in Milan since 1975-76. There was also Marco Leoni and Ciccio Pansacchia, but they work in Brazil. Maybe someone else had a machine but we didn't know that. It's another world without the internet!

What were the early years of Tattooing Demon like, and who were your customers?

I had all sorts of different people, not just young people, but people of very different ages, status and culture. A very wide range, but probably with some things in common too.

How did you deal with the more unruly ones?

None of them were unruly. And even if they were, a tattooer was always respected. If they weren't, there was always a nice baseball bat to remind them (laughs). Tattooers have always been gentlemen. But not too gentle.

Did you ever have occasion to use that baseball bat?

Fortunately, no. I was able to manage and get respect. We were the 'man with the power'. The customers, even the meanest ones, when they came in, they were entering wonderland, the place they dreamed of coming to one day. So they were like children, calm and respectful. A tattooed man in those days was respected. There was still the idea of the tough guy. And Italy wasn't like the United States or England. People were more educated, even the crooks.

What designs have your customers been asking for, and how have they evolved over time?

Roses, seagulls, eagles, lions, snakes, hearts - all these old images have gradually been replaced by others that are more fashionable: tribal, Japanese, techno, fantasy, and so on.

You didn't just tattoo, you wrote a book about tattooing (The Sign Upon Cain, 1985), when there was very little information available. What was your intention?

It was an idea from the publisher, who never intended to write a book. But there was no publication in Italian and that's how the idea came about... I'm still being asked to write another one with old stories, but I'm not a self-referential person. These days, everyone writes a book just to get their name in print. Frankly, I don't give a damn. That's not my world any more.

Why was this?

The tattoo used to be a mark of memory, of love, of hate, of freedom, of belonging to a group and a society, a tribe. Today, it's as if it's lost its meaning.

Don't you like what the world of tattooing has become today?

The Internet and social networks have taken up too much space. There's too much technology and not enough brains. Tattooing is fashionable and "lucrative", so people are getting into it. It's becoming like Only fans. Too many tattoo artists and not enough tattooers.

What distinction do you make?

A tattooer is a craftsman who does tattoos. He makes and leaves a sign. Good or bad, but he leaves behind a dream. Nowadays, tattoo artists do beautiful work but rarely leave a dream. For me, they're more like dermo-illustrators. The Internet and social networks are changing a lot of things.

What are you doing now? Are you still tattooing?

No, very little, just for pleasure. I don't have anywhere to do it. In Europe, I'm sometimes invited to the Tattoo Museum in Rome. I'm currently living in Vietnam and enjoying my retirement, earned from my work as a steward and tattooer. It's still very modest. I can't live decently in Europe. Anyway, life is better in Asia. There's the sea, peace and quiet, the food is good and I have a nice girlfriend. What else is there?