With a background in skateboarding and street culture, Dijon-born French photographer Brice Gelot has gradually moved into photojournalism. Interested in gangs, he has documented the place of tattoos in Californian Chicano culture and the Italian mafia, creating a personal synthesis of information and art. Brice has just published the first retrospective of his work, soberly entitled "Archives Book Vol.1".

The street, graffiti, tattoos, gangs - how did you come to photograph street culture and for how long?

I started photographing in 2004 in the skate scene for magazines and brands, and the rest came on its own. I've always been influenced by the whole culture.

You seem to be particularly interested in gangs, can you tell us about your work on this subject?

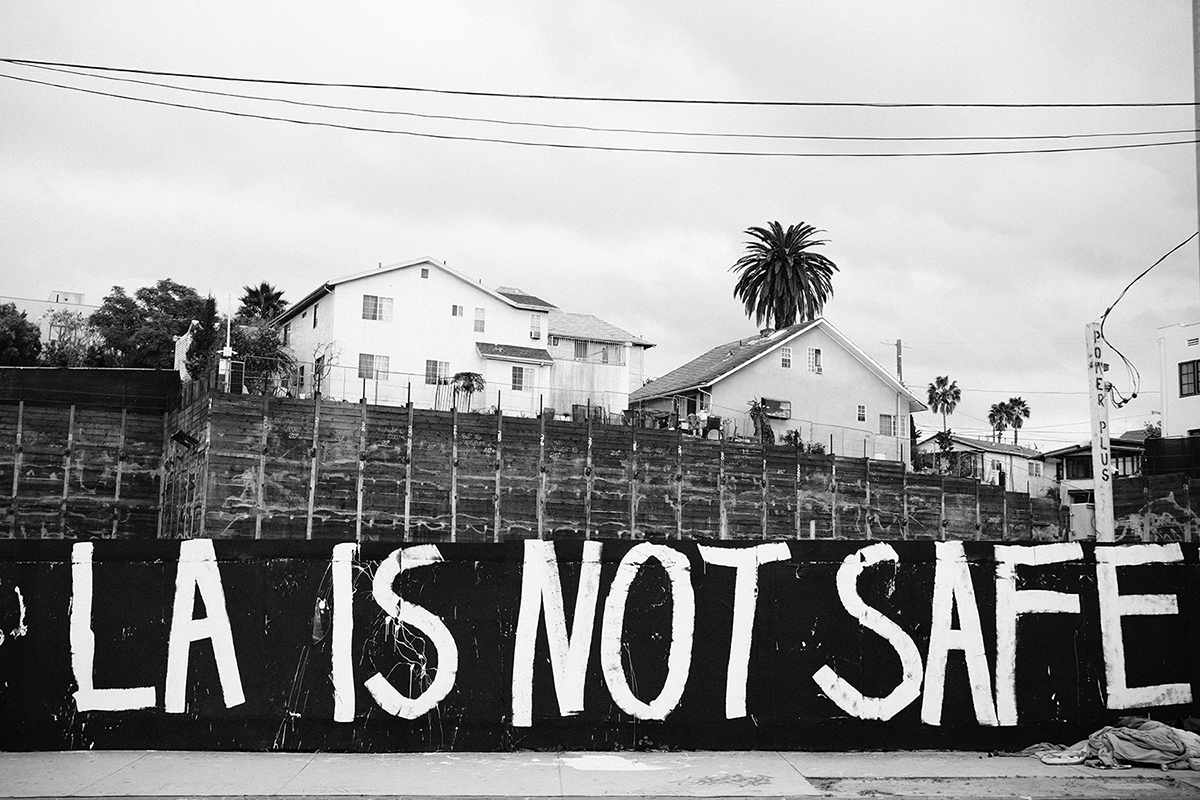

"Straight out the hood" is a series that shows the problems in inner-city areas. Where I can find chaos, I find beauty. I let the street do the talking and I simply document what I see... It gives us a better understanding of the social and economic challenges facing certain communities. As a photographer, I like to show the world as it is, for me nothing is more interesting than reality.

You spent some time in Los Angeles, in the United States, and enjoyed the Chicano culture. Why is that?

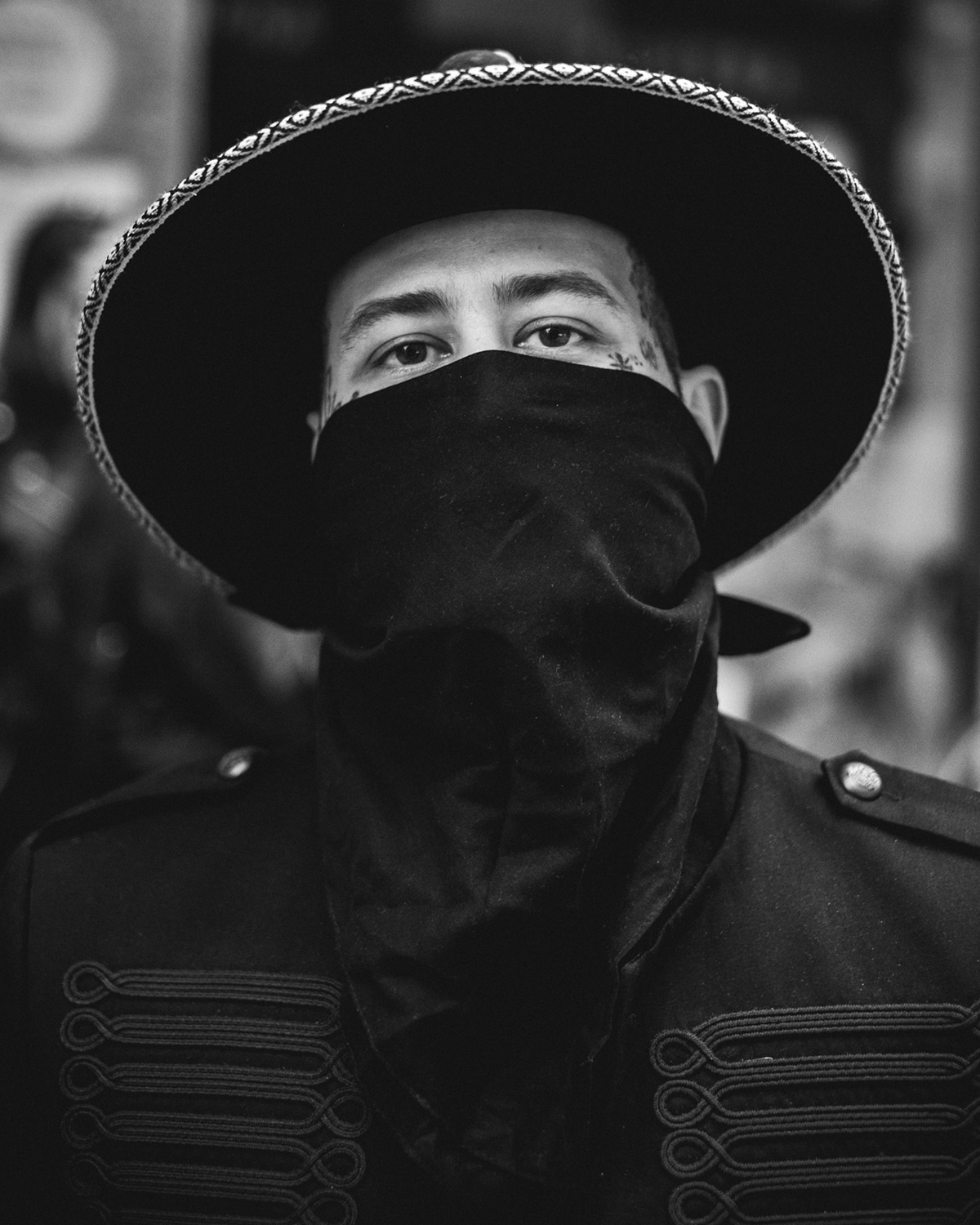

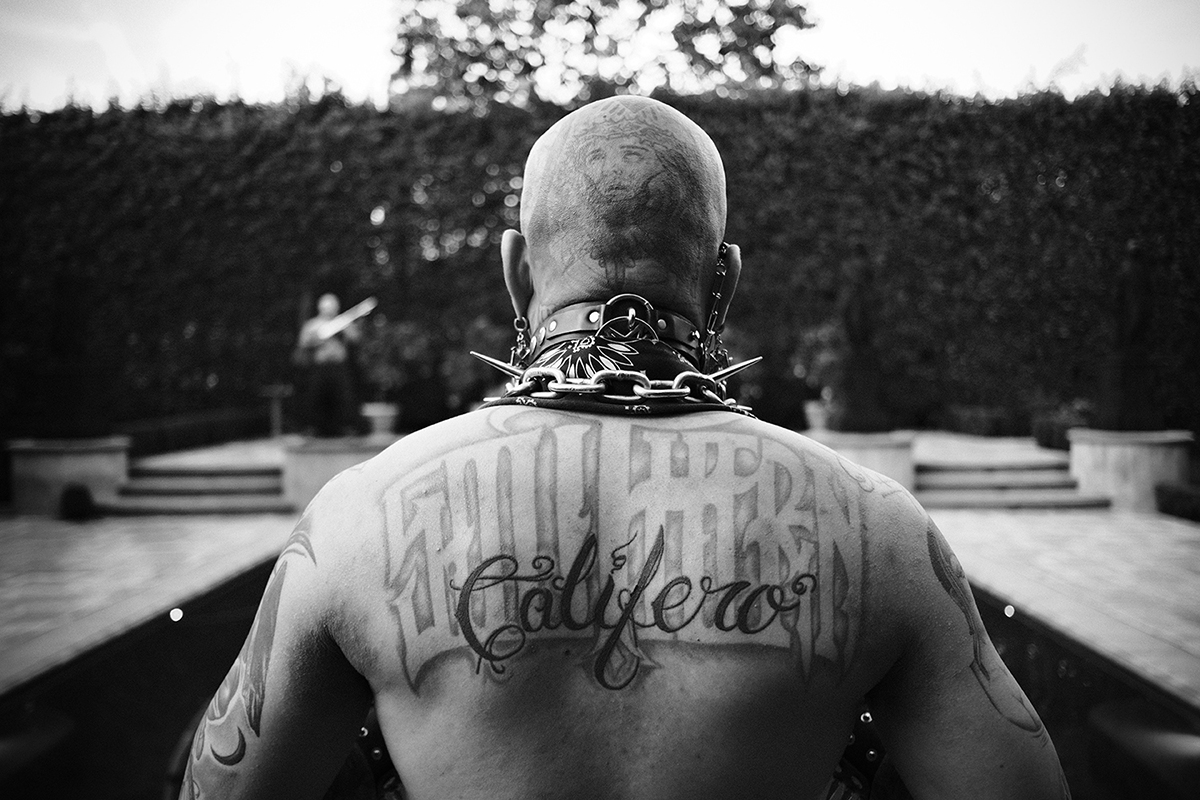

Chicano tattoo art is a distinctive style that celebrates the identity and culture that is part of Los Angeles. It reflects a hybrid identity and shared history between Mexico and the United States, marked by the struggle for equality and recognition. This culture encompasses diverse aspects such as tattoo art, music, literature, cuisine, language and religious traditions. It often highlights the struggle for civil rights, ethnic identity and social justice. Chicano art, for example, is characterised by motifs and themes inspired by Mexican culture, as well as expressions of political and social resistance.

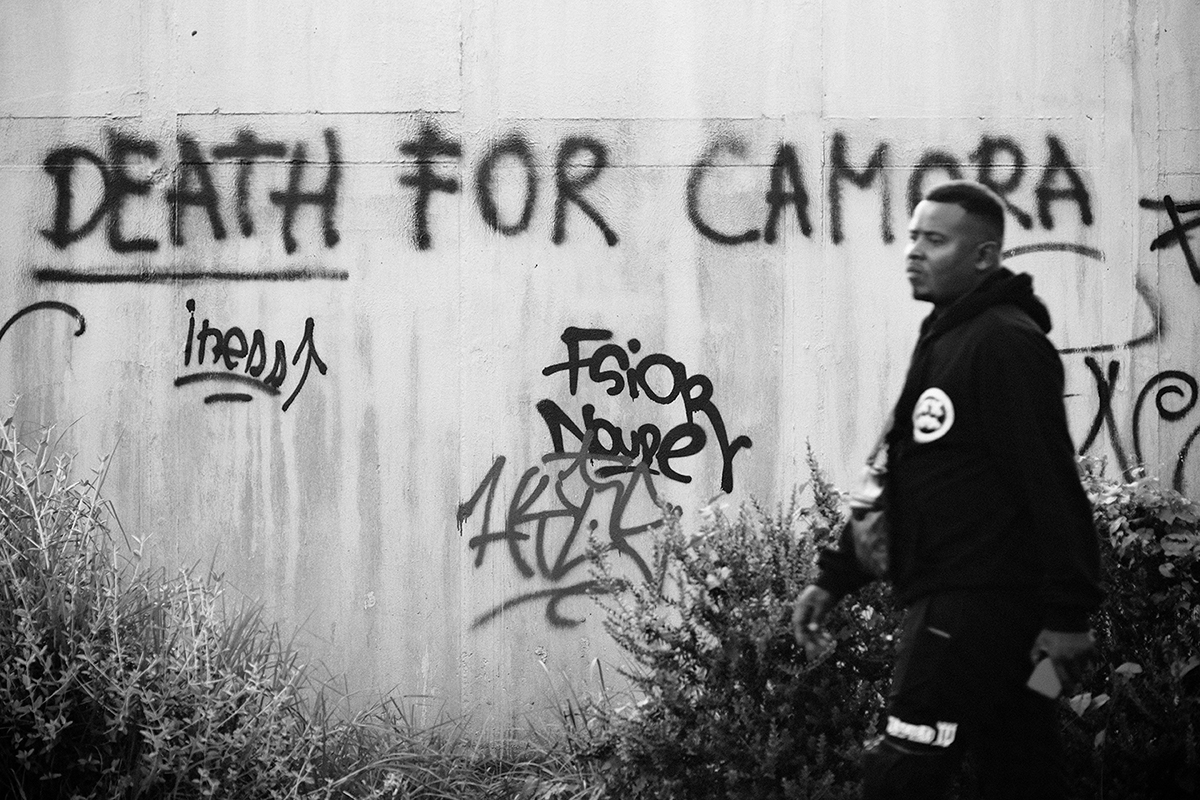

You've also worked in Europe, and I'm thinking in particular of a recent report you did in Naples in the Scampia district, well known as an epicentre of the Italian mafia. Can you tell us about it?

I went to Naples in 2022 to document life in Scampia, a working-class district, the most dangerous in Europe, and the birthplace of the Camorra mafia. The fight against the mafia in Italy remains a constant challenge, but there are ongoing efforts to promote justice, safety and well-being in neighbourhoods like the Velle di Scampia. For all my reports I take the time to document what I have to do, depending on the project, which can take from a few weeks to a few months.

In France, organised crime is also very active and we hear a lot about Marseille, for example. Is this an area in which you have taken an interest?

Not yet, but like all my other reports, it takes time and organisation to get to grips with other cities, towns and neighbourhoods around the world, so Marseille may be one day.

How difficult is it to come into contact with gang members?

There are risks to my personal safety, professional secrecy and external pressure from the authorities, but also ethical problems...

We can imagine that it can't be easy being in contact with this population. How do you feel about the notion of danger?

Photography can't change the world, but it can show reality, especially when the world is changing. It's all about respect, communication, planning and preparation, and awareness of the environment, depending on the location.

Can you tell us about some of your most memorable encounters?

All of them, but if I have to choose one, it's the one I met a hitman for the mafia in Naples during my report on Scampia. His story is a touching one: his mother was murdered when he was 9. He joined the mafia for revenge, served his time in prison and is now fighting to get out, change and become a better man.

Do you consider yourself a photojournalist or a street photographer?

I'm both, because I do both art photography and journalism. I tell stories through my images, whether by capturing moments of everyday life, historical events or social problems.

What reactions do you hope to evoke in viewers through your work?

I aim to inspire empathy and understanding for those who often go unnoticed or are simply ignored. I aim to challenge the viewer's preconceptions and highlight the resilience and strength of those who persevere in the face of adversity.

Can images change things?

I believe that images can be a powerful tool for social change and can facilitate important conversations about the most pressing issues of our time. They can raise awareness, educate and promote intercultural dialogue by highlighting the differences between cultures and ways of life in disadvantaged areas and other communities. I want to help by breaking down stereotypes and promoting greater understanding, but also to reflect on important issues such as poverty, the humanitarian crisis, social justice and human and women's rights.

When did you start documenting the tattoo scene?

Being in this community myself, I'd say very early on, probably in the 2010s.

What do tattoos represent for these gangs?

Tattoos can represent many things, depending on the country, city and community, because some tattoos are used to identify membership of a particular gang. This may include symbols, initials or codes specific to the gang. They may also indicate a member's rank or position within the gang. Specific symbols or markings may be reserved for high-ranking members or leaders. Some tattoos may be marks of criminal achievement or loyalty to the gang, such as dates of crimes committed or symbols linked to illegal activities. And tattoos can serve as a means of protection within the gang, showing allegiance and deterring members of other gangs from attacking them. Finally, although less common, some gang members get tattoos for personal or artistic reasons, reflecting their own beliefs or life experiences.

For a long time, tattoos were a marker of marginality, a factor of intimidation, but today, with their democratisation, what uses do people make of them?

Today tattooing has become a versatile means of personal expression, body embellishment and cultural connection, far removed from its initial association with marginality and intimidation.

In terms of equipment, how do you work?

I work with Fujifilm, both for my hybrid bodies and lenses. I also use film cameras that I collect or use for various personal projects.This first archive book is much more than a simple compilation of images. This period, from February 2022 to July 2023, was marked by the consolidation of strong photographic series, which have become the basis of a long-term work. This book is an attempt, on the one hand, to present this thematic work in a tangible and chronological way, but also to observe its evolution over time. It's an authentic plunge into my world, into the heart of street culture. The book was also born out of a desire to pay tribute to all the people who have crossed my path, with whom I have shared rare and sometimes intimate moments, and who have nurtured my reflections on crucial themes. Beyond simple visual capture, my aim is to lead the viewer to transcend clichés and familiar street scenes to foster a deeper understanding of different cultures and ways of life, particularly on the issue of disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

In terms of street photography, which photographers do you like to refer to?

Ed Templeton and Ricky Adam, because they're the ones who got me into photography in the first place, and they were a source of inspiration when I started out. + IG @bricegelot @nsd.5150 https://www.nsd5150.com/